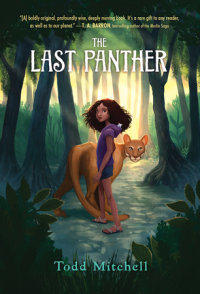

The Last Panther

Author Todd Mitchell

For animal lovers and fans of The One and Only Ivan and Hoot, this is the uplifting story of a girl who discovers a family of panthers that were thought to be extinct, and her journey to save the species.

Eleven-year-old Kiri has a secret: wild things call to her. More than anyone else, she’s always had a special connection to animals.

But when Kiri has an encounter with the last…

For animal lovers and fans of The One and Only Ivan and Hoot, this is the uplifting story of a girl who discovers a family of panthers that were thought to be extinct, and her journey to save the species.

Eleven-year-old Kiri has a secret: wild things call to her. More than anyone else, she’s always had a special connection to animals.

But when Kiri has an encounter with the last known Florida panther, her life is quickly turned on end. Caught between her conservationist father, who wants to send the panther to a zoo, and the village poachers, who want to sell it to feed their families, Kiri must embark on a journey that will take her deep into the wilderness.

There has to be some way to save the panther, and for her dad and the villagers to understand each other. If Kiri can’t figure out what it is, she’ll lose far more than the panthers—she’ll lose the only home she’s ever known, and the only family she has left.

2018 Green Earth Book Award Honor

2018 Colorado Book Award Winner

CAL Book Award Winner

Green Prize for Sustainable Literature Award Winner

A Bank Street "Best Children's Book of the Year"

A National Geographic Giant Traveling Map of Florida Selection

"A powerful tale of a future to be avoided." —Kirkus Reviews

"An eerie cautionary tale about the dangers of not protecting the environment, tackles an important theme in a compelling way...a fantastical tale with roots in real-world issues." —Booklist

"Earnest, heartfelt, and passionate, this book will likely inspire new environmentalists." —Bulletin

"A boldly original, profoundly wise, deeply moving book. It’s a rare gift to any reader, as well as to our planet.”

—T. A. Barron, best-selling author of the Merlin Saga

An Excerpt fromThe Last Panther

–1–

The Secret Heart of Wonder

The netters were pulling something to shore. Kiri couldn’t see what they’d caught from where she stood on the beach with Paulo, but six or seven netters had waded into the surf to haul on the lines, so whatever the nets held, it must have been big.

“That looks like your da,” said Kiri, pointing to the netter farthest from shore. He had black wavy hair like Paulo, and his red shirt was soaked with salt water. It clung to his darkly tanned arms as he tugged on the lines and called out orders to the others. His patched and weathered skiff bobbed in the waves beside him.

“It is my da,” said Paulo.

“What’s he got?”

Paulo cupped his sandy hands over his eyes and squinted. Late-afternoon sunlight glared off the surf. “Beats me. Everyone’s nets have been coming in empty lately.”

Clearly Charro’s net wasn’t empty. “Come on,” said Kiri. “Let’s go see.”

Paulo hesitated. “What about catching sand fleas?” He nodded to the trap they’d spent the better part of an hour digging on…

–1–

The Secret Heart of Wonder

The netters were pulling something to shore. Kiri couldn’t see what they’d caught from where she stood on the beach with Paulo, but six or seven netters had waded into the surf to haul on the lines, so whatever the nets held, it must have been big.

“That looks like your da,” said Kiri, pointing to the netter farthest from shore. He had black wavy hair like Paulo, and his red shirt was soaked with salt water. It clung to his darkly tanned arms as he tugged on the lines and called out orders to the others. His patched and weathered skiff bobbed in the waves beside him.

“It is my da,” said Paulo.

“What’s he got?”

Paulo cupped his sandy hands over his eyes and squinted. Late-afternoon sunlight glared off the surf. “Beats me. Everyone’s nets have been coming in empty lately.”

Clearly Charro’s net wasn’t empty. “Come on,” said Kiri. “Let’s go see.”

Paulo hesitated. “What about catching sand fleas?” He nodded to the trap they’d spent the better part of an hour digging on the beach. “Tide’s almost in.”

“The sand fleas will be here later. Whatever’s in that net might not.” Kiri hoisted her bag over her shoulder, fixing the strap so it wouldn’t bite into her skin. The vials of seawater she’d collected made the bag heavy, but Kiri was used to carrying it. At eleven, she was small but strong, thanks to years of trekking to the beach every day to collect water samples for her da. Paulo often claimed he couldn’t even lift the bag when it was full, although that probably had more to do with his laziness.

Snowflake, Kiri’s rat, poked his head out of her hood to investigate what all the fuss was about. His whiskers tickled her neck as he climbed onto her shoulder and sniffed. “Sorry, Snowflake,” said Kiri. “Nap time’s over.”

Paulo smirked at the little rat. “If you’re not careful, the netters might try to catch him,” he teased.

“Hush! You’ll scare him,” said Kiri. “Snowflake is a very sensitive creature.”

“I’m serious. People in the village are getting so hungry, I bet they’d make rat stew. Come to think of it, that’s not a bad idea. He looks delicious.”

Kiri lifted the rat off her shoulder and scratched the white star on his head. “Don’t listen to him, Snowflake. Paulo’s joking. He always jokes.”

She set Snowflake back on her shoulder. He chittered at Paulo before returning to his hiding place in Kiri’s hood. When she let her wild brown hair--“motherless hair,” the women in the stilt village called it--tumble over her back, no one could even tell the little rat was there.

A shout from up the beach called Kiri’s attention back to the netters. Fugees from the nearby stilt village had started to gather around them. Whatever Charro had caught, it wasn’t coming in easily.

“It could just be a tire, or some other salvage,” said Paulo, squinting into the sun.

“Think your da would need six netters to bring in a tire?”

“Good point.”

Paulo finally left the sand-flea trap and joined Kiri. Together, they ran toward the crowd gathering on the beach. Snowflake bounced slightly in Kiri’s hood, but he was used to holding on. He dug his tiny forepaws into her collar and stretched his hindquarters down so he wouldn’t fly out.

“Paulo!” shouted Tae, Paulo’s older brother, as they approached. “Get over here!”

Paulo didn’t leave Kiri’s side. She felt grateful to him for that. Ever since they were six and Kiri had wandered into the stilt village for the first time on her own, she and Paulo had been best friends.

Tae shouted to Paulo again, waving for him to come into the water and grab part of the net.

“I better go,” said Paulo. “Tae will snap a line if I don’t help.”

Kiri nodded. She wished she could join the netters in the surf as well, but she knew she wouldn’t be welcome. Only fugees with a catch share were allowed to pull in the nets.

Still, she felt called by more than curiosity to see what the netters had caught. And so she followed Paulo, ignoring people’s grunts and complaints. When she finally made it through the crowd, what she saw made her heart kick.

At first it looked like a huge log bobbing in the surf, except it was wider than any log Kiri had ever seen--as wide as Charro’s skiff, even, with a ridged shell-like back and a stout, tree-stump head. Enormous flippers swirled the waves as the creature tried to swim away, but it couldn’t escape. The lines of the nets had tangled around its limbs, and they tightened with every pull. The creature’s shiny black flippers, shell, and head were all dappled with white spots like the sky at midnight. Its odd teardrop-shaped body reminded Kiri of a giant sunflower seed, if sunflower seeds could swim and were bigger than four gators put together.

Paulo joined his brother in pulling the nets in, as if his skinny arms would make a difference. Kiri stuck close behind him, but she didn’t grab the nets. Instead, she wished she could do the opposite and get everyone to let the creature go. No one would listen to her, though. What netter worth his salt would release such a catch?

She stepped farther into the water, not caring if her shorts got wet or if jellies stung her legs. Snowflake prodded her back as he nuzzled deeper into her hood, avoiding the shouting voices and the spray of the surf. The little rat hated getting wet.

“Hup! Hup! Pull!” yelled Charro to the netters each time a wave surged. “Step back!” he shouted to villagers who pressed too close.

Kiri didn’t step back. She felt as if the fishing nets and lines were wrapped around her limbs, tugging her closer to the creature emerging from the surf. Barnacles pocked the edge of its shell, and its wrinkled skin looked thick and ancient. It faced the waves, but on land its massive flippers were cumbersome and slow, flailing in the sand.

A big wave came in. Charro barked more commands and the netters heaved the creature farther up the beach. Then the water receded, and for the first time, Kiri saw its eyes. Framed by thick gray lids, its eyes were larger than her fists and a deep, entrancing blue. The creature lifted its tree-stump head and fixed its bottomless gaze on her.

Kiri’s breath caught. She’d always had a way with animals. It was why she was good at catching things, and why, if one of the netters would take her out on a skiff, she knew she could find some fish and prove herself to the villagers. She always seemed to know where creatures wanted to be, in part because she tried to think like them, and in part because of a whispery sense she sometimes got that they were speaking to her. But what she felt now, as she peered into the creature’s eyes, was more than any whisper.

Another wave broke and the netters heaved the giant still farther up the beach. The creature opened its hard-lipped mouth, but it made no sound. No sound in the air, at least. In Kiri’s chest, though, she felt something like the rumble of thunder and she heard the hurricane roar of wind through palm branches--a rising, primal call that made her body quiver and her pulse race.

The waves that had given them shipwrecks and storms, washing ashore countless dead fish, along with salvage they sold to the boat people, had now surrendered this. To Kiri it seemed as if the secret heart of wonder itself had been hauled from depths unknown and made to flop on land. With its wrinkled midnight skin and its stunning blue eyes, it appeared both old and new. Both familiar and strange. She had no name for it. This giant’s tear. This ocean’s seed. This earth’s ancient, forgotten dream, suddenly remembered.

–2–

The Once-Were Creatures

At night, before Kiri slipped off to sleep, her da sometimes told her stories of the once-were creatures.

He spoke of ones with necks so long they could eat the leaves from the tops of trees, scraping them off branches with black tongues longer than her arm while teetering on stilt legs.

And he spoke of ones that stood bigger than houses, with python noses that could lift a boat, and curved teeth as big as oars. He said they traveled in herds, like an entire village of houses moving across a field.

He told her of enormous ice bears, with white fur and black skin. And hairy giants, three times the size of men, who could talk to people with their hands. And white sea beasts with spiral horns sharper than spears. And jeweled birds that could hover in place and suck the sweet from flowers. But her favorite once-were creatures were the blue waterlords who were longer than six skiffs in a row. Da told her stories of how they made waves with their fins and sang songs in trilling, mournful voices that lasted for days. Songs, he claimed, that were too complex for human ears to hear.

When she was younger, Kiri actually believed such wondrous creatures had existed. The only proof her da ever offered, though, were drawings in some of the rotting waller books he kept in plastic bags and wouldn’t let her touch. And most of the faded drawings he showed her were of creatures that seemed too big or strange to be real. As she got older, Kiri asked others in the village about the once-were creatures. All the fugees who’d been places and knew something of the world laughed and shook their heads at her waller stories, until she finally came to believe that the once-were creatures were just mythical things.

Now, though, staring at the huge blue-eyed creature digging its flippers into the beach, she wasn’t so sure. If something like this, that was as big and strange as any once-were creature her da had ever spoken of, could exist, then couldn’t others exist as well? Other water giants, and flying jewels, and long-necked spotted horses on stilts?

Charro climbed onto the creature’s ridged shell-like back and stood above the crowd as if he were standing on an overturned skiff. The creature raised its mighty head to shake him off, but it could barely move its bulk on land. It looked longingly at the receding waves, then lowered its head and closed its ponderous blue eyes, not struggling anymore.

“What is it?” asked one of the younger netters.

“I’ve never seen anything like it,” said someone else. “It’s amazing.”

“It’s salvage!” announced Charro. His round belly poked through his open shirt, making him look like an overgrown, boastful toddler. But his eyes were sharp, and his bronze skin had been scarred and toughened from many years of fishing. There was little resemblance between Paulo’s skinny, goofy presence and his father’s large, stern one.

“Salvage, that’s all,” continued Charro. “I spotted it out beyond the breakers and I claimed salvage rights to it then and there. Tarun heard me.”

“That’s true,” said Tarun, a quiet netter whose words carried weight. “He did claim salvage rights.”

“So it’s mine,” said Charro. “Tomorrow, I’m taking it to the boat people to trade.”

Nessa, Paulo’s favorite aunt, threw down the clumps of net she’d been holding and crossed her arms. “It’s not salvage if it’s alive, Charro. It’s a catch, and we all helped pull it in. All of us here.” She nodded to the other netters, many of whom were wet from the surf and had raised spots on their legs from jellyfish stings. “Which means it’s part of the catch share, so we all get to decide what’s done with it.”

A few netters grunted in agreement. Nessa’s expression was all angles and hard edges, with her straight black hair pulled back tightly from her face in a way that made the bones beneath her cheeks stand out.

Charro waited for the mutters to subside before he spoke. “Does this look like a fish to you, Nessa? Does it look like a fish to any of you?” he added, addressing the crowd. “No? That’s because it’s not. It’s salvage.”

The netters who sided with Charro nodded. Still, some weren’t persuaded and they took up Nessa’s side of the argument. “It’s a catch,” said one. “You can’t claim salvage rights to a catch.”

Several women and elders joined the argument. With how scarce food had been lately, tempers were close to the surface, and soon the rumble of voices rose above the crash of waves.

Amid the clamor, Kiri noticed the old Witch Woman making her way through the crowd. She moved stiffly, her bad foot leaving sideways tracks in the sand. She was so slight that she was able to weave through gaps between arguing villagers without causing a fuss, until she stood in the open space near the creature’s head. The creature lifted its round snout off the sand in response.

A hush spread through the crowd. Kiri wanted to shout a warning. Even though the creature was slow and cumbersome on land, all it had to do was open its massive jaws and snap once and it could break the Witch Woman in half. Others must have seen this danger as well, but no one spoke. No one dared. Everyone was stuck in the peculiar silence that descends the moment before disaster strikes.

Only, no disaster came. The Witch Woman stretched her knobby hand toward the creature until her fingers rested on its round snout, like a bird perching on a sinking ship. The huge creature gave her a long, weary look. Then it huffed out an enormous breath, blowing the Witch Woman’s gray hair back. Still, she didn’t move.

“It’s no catch,” she said in a driftwood voice. “It’s no salvage, either.”

“Then what is it?” asked Charro, glaring down at the Witch Woman from atop the creature’s back.

“A portent,” she said.

“A what?”

The Witch Woman ignored Charro, focusing instead on the netters, elders, and children gathered around her.

“It’s a messenger,” she said. “A devi sent by the Wise One.”

Hushed murmurs spread through the crowd. Fugees rarely spoke of devi out loud. Some considered them gods, or fragments of gods that walked the earth. Others considered them demons. Or angels. Or both.

Once, after seeing Nessa make an offering to a devi before rowing out on a gray day, Kiri asked Paulo what devi were. “Devi are devi,” he told her. “There’s no other word for them.” So all Kiri knew about devi was that some could be good, and some could be bad, but all were best respected.

“If it’s a devi sent to bring us a message, then what’s it saying?” asked Senek, a pale, sandy-haired netter whose face always looked red and sunburned. He often drank palm wine with Charro under his stilt house at the end of the day.