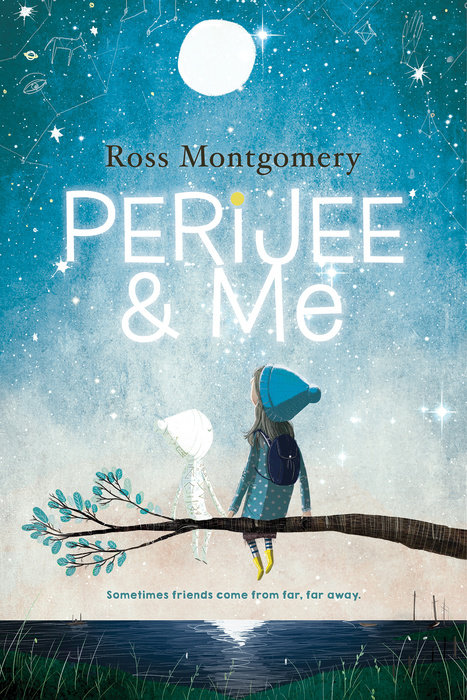

Perijee & Me

Author Ross Montgomery

Perijee & Me

Perijee and Me is a hilarious and touching story about an unusual friendship, a heart-stopping adventure, and the power of kindness when you’re faced with an alien invasion. If E.T. the Extra Terrestrial is still “right here” in your heart, then you’re sure to fall hard for the misunderstood Perijee and the one girl who’s desperate to save him.

Caitlin is the only young person living on Middle Island. On the first day of vacation, she…

Perijee and Me is a hilarious and touching story about an unusual friendship, a heart-stopping adventure, and the power of kindness when you’re faced with an alien invasion. If E.T. the Extra Terrestrial is still “right here” in your heart, then you’re sure to fall hard for the misunderstood Perijee and the one girl who’s desperate to save him.

Caitlin is the only young person living on Middle Island. On the first day of vacation, she finds a tiny alien on the beach. Caitlin becomes close to her secret friend, whom she names Perijee, and treats him like a brother. Caitlin has a reading disability, but finds she is a good teacher, telling Perijee everything she knows about the world.

There’s only one problem: Perijee won’t stop growing. And growing . . . Caitlin will have to convince the adults around her—and Perijee himself—that the creature they see as a terrifying monster is anything but. When things get out of hand, brave Caitlin embarks on a journey to save Perijee before it’s too late.

Praise:

"Elements of humor and an attractive jacket add to this chapter book's undeniable appeal." --Booklist

"A cute read for kids who like a strong dose of absurdity." --School Library Journal

"Montgomery's jam-packed narrative doesn't slow for an instant in this exaggeratedly comic drama. . . . Humor carries the day." --Kirkus Reviews

"Caitlin's desperation for friendship is palpable, and the book powerfully conveys the longing for connection that drives her to risky actions. This British import is earnest, often quietly thoughtful, and quirky." --The Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books

“Montgomery engages us with . . . high drama, hurtling towards a heartwarming resolution.” —The Sunday Times (London)

An Excerpt fromPerijee & Me

1

My best moment with Perijee happened when we were lying out in the cove. There weren’t any clouds that night, not one. If you opened your eyes wide enough, you could see all the stars together, looking down on us like a city in the sky. It was just me and Perijee and the waves coming in and nothing else for miles and miles. The sky had never looked so big to me before.

I tried to find one of the stars Dad had told me about, so I could show it to Perijee. He was still about my size then. This was before he tried to take over the world, etc.

“Perijee,” I said, pointing up. “Look.”

Perijee looked at my finger.

“No,” I said, pointing harder. “Look there. At that star.”

Perijee grew a finger on his hand and tried to show it to me. I groaned.

“No, Perijee.” I pulled his head down to my arm. “That star, at the end of my finger, is called Sirius. It’s the closest one to Earth—that’s why it’s so bright. See?”

Perijee…

1

My best moment with Perijee happened when we were lying out in the cove. There weren’t any clouds that night, not one. If you opened your eyes wide enough, you could see all the stars together, looking down on us like a city in the sky. It was just me and Perijee and the waves coming in and nothing else for miles and miles. The sky had never looked so big to me before.

I tried to find one of the stars Dad had told me about, so I could show it to Perijee. He was still about my size then. This was before he tried to take over the world, etc.

“Perijee,” I said, pointing up. “Look.”

Perijee looked at my finger.

“No,” I said, pointing harder. “Look there. At that star.”

Perijee grew a finger on his hand and tried to show it to me. I groaned.

“No, Perijee.” I pulled his head down to my arm. “That star, at the end of my finger, is called Sirius. It’s the closest one to Earth—that’s why it’s so bright. See?”

Perijee nodded.

“Maybe that’s where you came from,” I said.

Perijee glowed, like a candle in a jar. He grew more fingers, tens of them, wrapping them around my hands and wriggling.

“Home,” he said.

I smiled. “That’s right, Perijee! Home!”

(I felt a bit bad, actually, because right then I realized Sirius was way off in the other direction and I’d been pointing at the wrong star the whole time. It might have even been a plane. I don’t think Perijee noticed, so it’s no big deal.)

We stayed like that for hours, him with his head on my shoulder and the waves hissing at the stones by our feet and his whole body glowing and fading like a night-light, while I made up the names of the stars.

“That’s the Jam Tart. And that’s the Angry Horse. And that’s the, er . . . Flying Fish.”

Perijee listened until he fell asleep, and when it was properly late I carried him back across the beach in my arms and laid him in the hut by the jetty and tucked him under the nets.

It was my most special moment out of all the times we’d spent together, easy. Because as I stood there in the middle of the cold, dark hut and watched him sleep, I realized for the first time how small he was. Even though he was my size.

He didn’t look like an alien at all. He looked like a baby.

And right then I knew that no matter what happened to Perijee and me, no matter how much we changed, it was my job to make sure that he was always safe and always loved and always happy.

Otherwise, what’s the point of being a sister?

2

It all started just like any other morning, except I was holding a pineapple and the cove was covered in ten thousand dead jellyfish.

The cove wasn’t normally covered in dead jellyfish. Normally it was covered in shingle, which is like rubbish painful sand. It was pretty much the only thing there was on Middle Island—that’s why no one else lived there, apart from me and Mum and Dad.

By the end of that day, lots of other things would be different—in fact, everything would be. But I didn’t know that then. All I knew was that I had a pineapple.

Frank’s boat finally appeared, creaking through the cove in a cloud of smoke.

“You’re late!” I shouted.

Frank was always late. He made me miss the school roll call so often the others in class had started calling me “Late-lin” instead of Caitlin, which is my name. When I asked if they could call me something else, they changed it to “the weirdo who just moved here and who can’t read or write properly,” which is what they stuck with for the rest of the year.

Frank used to be a local fisherman, but he wasn’t very good at it, so Mum and Dad hired him to drive me to school every day instead. He has long hair like a lady and a big bushy beard, and doesn’t do any normal grown-up things like own a car or wear shoes.

He stopped the boat beside the jetty and stared out.

“Jeez,” he said.

“It’s a pineapple,” I explained. “We all have to bring in food.”

Frank pointed behind me.

“I was talking about the jellyfish, Caitlin.”

“Oh yeah,” I said. “Them.”

I climbed into the boat while Frank shook his head some more.

“Never seen anything like it. . . . Dead fish everywhere, boats wrecked, flooding all over the mainland . . .” He turned to me with a grin. “Some storm, eh?”

“What storm?” I said.

Frank was surprised. “The one last night, sprat. With all the thunder and lightning.”

I shook my head. Frank frowned.

“And the gale-force winds? The twenty-foot waves? The massive meteor shower that people saw all over the world?”

“That sounds exciting,” I said.

Frank glared at me. “Yes, Caitlin! It was the biggest storm in years! People thought it was the end of the world! How did you miss it?” He pointed across the cove. “Look—on the other side of the island there are shrimp washed up on the beach that are bigger than—”

“Wow!” I gasped. “You can see that far away, even with your—”

I suddenly realized what I was saying and stopped. The other thing I should mention about Frank is that he has a glass eye. Sometimes I really want to ask him about it—like if his old one’s in someone else’s head, so he can swivel it around and look at their brains—but that would be impolite, so I never mention it.

“You’d better not be going on about my bloody eye again,” Frank muttered.

The engine belched and we set off for the mainland.

“So,” said Frank after a while. “Nice pineapple.”

I beamed. “Thanks! I thought I’d bring in an exciting fruit, seeing as it’s the last day of term.”

Frank whistled. “Summer holidays! Ooh, you jammy git. I’d love six weeks off work.”

“You don’t have a job,” I pointed out.

Frank scowled at me. “What about you? Anything exciting planned for your time off?”

Of course I did. I’d been planning it for weeks.

“I’m going to have a party on the island!” I said. “I’m inviting the whole class today!”

Frank looked amazed. “Wow! Your parents don’t mind having that many people over?”

“I’m sure they won’t,” I said.

Frank’s smile disappeared.

“You have asked them, haven’t you?”

“Of course I have!” I said. “I mean, I will, eventually. But let’s face it—they’ll both be too busy to care what I do over the holidays anyway. Dad’s not back from his book tour for months, and Mum’s got a big deadline, so she’ll be on the computer every day. Even more than usual.”

Frank shifted nervously beside me.

“Look, sprat—I’m not sure having a party is such a good idea. Why not just invite a couple of mates over?”

I groaned. “I’ve tried that! I invite people from my class all the time, but they’re always busy—every single weekend! I mean, how am I supposed to make friends if no one ever comes over?” I laughed. “It’s almost like they’re making up excuses not to come, because they all think I’m a complete dork. Or something.”

We made a big turn in the water and the mainland appeared up ahead. You could make out the school already—it was the biggest building for miles. It had taken a real battering in the storm. There was a dead octopus hanging from the flagpole. A whale was stuck on the street outside and blocking traffic.

“But if I invite the whole class at the same time,” I said, “then someone’s bound to be free, right? For one day in six whole weeks?” I sighed. “I mean, if they’re not . . . I’ll be on my own all summer. And that would be awful.”

Frank said nothing. We pulled into the harbor and I leaped out.

“Well, see you after school!” I said. “I might be a bit later than normal, because I’ll be taking suggestions for cake flavors and—”

“Caitlin.”

I turned around. “Yes, Frank?”

Frank thought about saying something, then changed his mind. He smiled instead.

“Nothing,” he said. “I hope your plan works out. Good luck, sprat.”

I gave him a big grin and ran to school, clutching the pineapple to my chest. I was so excited—I was finally going to make some friends, for the first time ever! It was nice of Frank to say it, but I didn’t need any luck.

Why would anyone say no to a party?

3

I left before everyone else when the bell rang at the end of the day and walked quickly down to the harbor. I only stopped to throw my pineapple at a wall and stamp it into chunks.

I was much faster than normal, so Frank was still smoking by the time I got to the boat. He started coughing when he saw me and threw his cigarette into the water.

“Jeez!” he said. “You’re in a hurry!”

I got straight in.

“Er . . . everything all right?” said Frank.

I sat and waited. Frank bit his lip, then quickly turned on the engine. We drove off in silence. The waves smacked against the front of the boat and the mainland slipped out of sight behind us. Frank glanced over at me.

“So . . . went well, did it?”

My lip started trembling.

“Oh no,” said Frank. “Please don’t start crying.”

I did. I sprayed tears all over the place. Tears and worse. Frank looked like he was trying to sail through a hurricane.

“Argh . . . Oh god . . . There’s bound to be some tissues somewhere. . . . Take the wheel, will you?”

I steered and sobbed while Frank looked for tissues. Eventually he came back with an old tea towel he found under a chum box.

“Want to talk about it?” he said gently.

I shook my head. “You wouldn’t understand. Schools were completely different when you were my age. They hadn’t even discovered electricity.”

Frank frowned. “I’m forty-two, Caitlin.”

“You’d have had candles instead of computers, and horses instead of—”

“Just tell me what happened.”

My eyes filled up again.

“They all laughed at me,” I said quietly. “The whole class. No one wants to come over.” My voice started trembling. “I’ve got to spend the whole summer . . . by myself!”

Right on cue Middle Island appeared up ahead, gloomy and gray with clouds. It looked even emptier than usual. I burst into tears again. Frank pulled up by the jetty and turned the engine off. We sat and floated in silence, clouds of jellyfish lapping against the sides like bubble bath.

“I’m sorry they laughed at you, sprat,” he said. “They shouldn’t have done that. I know what it’s like to be lonely around here. Some days you’re the only person I talk to, apart from the fish.”

I looked at him suspiciously. “You talk to the fish?”

“That’s not what I meant,” Frank muttered. “I mean that I never married or had kids. It’s a tough life, being a bachelor at my age.”

I wiped my eyes. “But you’ve got friends—you talk about those guys down at the pub all the time! And there’s loads of people where you live on the mainland! On Middle Island it’s just me and Mum—and Dad, when he’s back from tour. . . .”

“Doesn’t mean you can’t get lonely,” said Frank. He patted me on the back. “It’s going to be tough for me these next six weeks, not seeing your face every morning. I’ll miss you.”

I glanced up. “You will?”

“Course I will!” said Frank. “You’re my friend, aren’t you?”

I felt like I was glowing.

“We’re friends?”

“You bet,” said Frank. “And I’ll be counting down the days until I can see you again.” He stretched out across the bench. “I’ll have to find some other ways to pass all my free time. A few long naps, maybe . . . a little fishing . . . a lazy stroll to the pub around lunchtime . . .”

I leaped onto the bench.

“Then that settles it!” I cried. “We’ll start Monday morning!”

Frank looked blank. “Start what?”

“Spending the summer together!”

Frank sat bolt upright.

“You what?”

“It’s the perfect solution,” I explained. “You’re lonely, I’m lonely. . . . We can hang out together instead! Every single day! That’s what friends do, right?”

Frank was so delighted, he’d gone pale. “But . . . but—”

“At least that way I won’t be so crushingly sad and lonely,” I added.

Frank didn’t speak for a long time. When he did, he was gritting his teeth.

“Fine,” he said. “I’ll come over. For one day a week—all right?”

I gasped. “Really?”

“Yes! Really!” Frank snapped. “But the second you start going on about me taking out my eye—”

I didn’t even let him finish. I gave him the biggest hug you’ve ever seen.

“Frank,” I said. “I don’t care what everyone else says about you—I think you’re the absolute best.”

Frank smiled. I couldn’t see it, but I could feel it.

4

I told Frank to come on Monday at dawn. He wasn’t too happy about it, but I insisted we start early so he could make me breakfast. I ran all the way home and charged straight into Mum’s study.

“Mum!” I said. “Guess what! I . . .”

She was still in her pajamas. She didn’t even move when I came in—just kept staring at the screen, typing. The cup of tea I’d made her that morning was still there, untouched.

“Mum,” I said again.

She turned around like I’d just spoken. She looked tired, as usual.

“Oh,” she said. “Sorry, pickle. I was miles away.”

Mum is a marine biologist. That’s someone who knows everything there is to know about life in the sea. She used to work on a boat in the middle of the ocean, right above the Mariana Trench—the really deep bit, where they find fish with lightbulbs on their heads.

But when we moved to Middle Island, Dad made her give up her job. He’s an astrobiologist—someone who knows everything there is to know about life in space. He’s written books about it, big, thick ones with his name and face on the front. He started doing book tours that went on for months, so Mum had to stay at home to do his paperwork for him.

“How was your last day at school?” she said, rubbing her eyes. “Did your friends like the pineapple?”

I hadn’t gotten around to telling Mum the truth yet—that I didn’t actually have any friends. But I couldn’t tell her now. When Mum’s busy, she gets upset at the slightest thing. The problem is, she’s always busy.