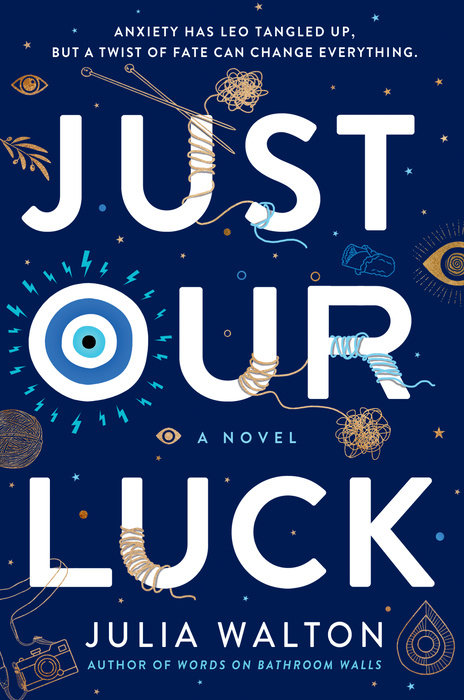

Just Our Luck

From the author of Words on Bathroom Walls—now a major motion picture—comes a romance in the spirit of Dear Evan Hansen about overcoming anxiety—and about finding love and friendship in unlikely places.

★ "A masterpiece" —Kirkus, starred review

"Bad luck follows lies." That was the first rule for life that Leo's Greek grandmother, Yia Yia, gave him before she died. But Leo's anxiety just caused a fight at school, and though he didn't lie, he wasn't exactly honest about how it all went down . . . how he went down. Now Leo's father thinks a self-defense class is exactly what his son needs to "man up."

"Leave the Paros family alone." That was Yia Yia's second rule for life. But who does Leo see sitting at the front desk of the local gym? Evey Paros, whose family supposedly cursed Leo's with bad luck. Seeing that Leo is desperate to enroll in anything but self-defense class, Evey cuts him a deal: she'll secretly enroll him in hot yoga instead—for a price. But what could the brilliant, ruthless, forbidden Evey Paros want from Leo?

Sharp, honest, and compulsively readable, Just Our Luck is as funny as it is heartwarming.

"A feel-good story, with shades of Holes and The Karate Kid" —Bulletin

An Excerpt fromJust Our Luck

1

I didn’t lie. Not really.

I just didn’t provide all the details.

Yia Yia would have said that’s lying too because you can feel it in your stomach when you’re holding something back.

Not holding back was the problem, though, because I lunged at him first. I just didn’t tell anybody that.

And I should have known better. It was rule number one of the two rules that Yia Yia drilled into my head before she died.

Rule Number 1: “Bad luck follows lies, agapi mou.”

Rule Number 2: “Leave the Paros family alone.”

Yes, he hit me. But that’s not the full story, and it would be lying to say that it wasn’t just a little bit my fault.

The thing with anxiety is that people think it makes you run from a fight, but that’s not always true. At least not for me.

Sometimes it makes you defensive.

What happens for me is that when that hot, panicky feeling rises up, I just need to get it out of my system, and sometimes the easiest way to do that is to be a jerk. Lash out as quickly as possible to get that instant relief of setting the bad thing free. Just as long as it leaves me alone--as long as it’s not gnawing on the hardware in my brain--I’m cool.

Anyway, it’s actually the school’s fault this happened. Service hours are required, and I’ve always signed up for the jobs that are mostly solitary, like reshelving library books. But this time they assigned us jobs, and someone thought it would be a good idea for me to sell candy at the Snack Shack.

It was the first day back from winter break, so of course the place was swarming with people holding their sweaty money from the holidays, trying to elbow their way to the cash register. And I was behind the counter, responsible for giving them the sugar to keep this orgy of energy going. Jesus Christ. What had I done to deserve this?

I kept telling myself it was only for today, but as more people filled the room, I started to hear a loud buzzing in my ears.

All the Sour Patch Kids went first. Then the fresh cookies. Then the Starbursts.

One guy, Jordan Swansea, gave me forty dollars for three big containers of Red Vines and told me to keep the change as he walked out and distributed them in handfuls to the rest of his impossibly tall group of jock friends.

Overpaying for Red Vines in the Snack Shack just so you can drop money on the counter in front of everyone and walk away is a classic symbol of douchebaggery. That’s probably unfair, but he has that kind of vibe. Maybe it’s not such a big deal for rich people. I wouldn’t know. My high school sits in the middle of a lot of wealthy neighborhoods, so even though my family has always been solidly middle-class, that almost translates to poor here.

That’s what I was thinking when Drake Gibbons, the second douchebag of the day, got to the front of the line. As I was counting back change, he interrupted me. I should probably note that he does that a lot. Interrupts, I mean. He’s been in my class since his family moved here in third grade, and he has always been annoying. He doesn’t really have a filter, which means he was usually responsible for the truest (and meanest) nicknames doled out in elementary school.

I was doing fine trying to ignore the noise and the people, but instead of waiting for me to finish, Drake grabbed a Clif Bar, dropped a wrinkled twenty into the cash box, and said, “Nineteen, dude.”

I would have pegged him for a Slim Jim kinda guy.

“Just a sec.” I was still helping this girl who was trying to pick out all the green apple Jolly Ranchers from the plastic box in front of her, but Drake didn’t want to wait for his change.

“Here, dude, let me help you with that.” He tried to reach into my cash box, but I pulled it back.

“Just a sec. I’m not done with that.”

Jolly Rancher Girl, who also went by Cassie and was in my algebra class, was taking her sweet-ass time pulling out her candy, and I was trying to move her along while Drake kept putting his hand over the counter to grab his change. It wasn’t clicking for him that I was still helping someone else. Like he heard me but didn’t hear me. If that makes any sense.

“Dude, I’ll help you. It’s nineteen bucks.” He was still leaning over the counter. Still in my space. Close enough for me to smell the protein shake on his breath. Cassie glared at him, but he ignored her too.

“Just wait,” I said, gritting my teeth. I put up my hand. The noise in the room was giving me a stomachache, and I had to start over counting back change for the second time.

Then Drake stage-whispered, “Uh-oh, better not make Fat Leo mad.”

I glared at him. Fat Leo was the best nickname he could give me as a kid. Since I subsisted on a diet of moussaka and souvlaki and my pudgy belly stretched most of my clothes, Fat Leo was a suitable choice, I guess, but completely without vision.

He swiped for the cash box, and Cassie once again tried to get me to finish her transaction. That’s when the crowd turned ugly.

“Some of us are HANGRY. Just give me my Funyuns, dude!” said a guy at the back.

“And breath mints,” said his girlfriend.

A bunch of people laughed, but a few other people started sounding really annoyed about the holdup.

The laughter rumbled in my head, making it feel like my temples had a heartbeat.

Why am I here around people and not hiding in a dark corner? Why isn’t that a service hours option?

There was another grab for the cash box, and as I yanked it out of Drake’s reach, I could see people watching with curiosity.

“Jesus,” said Drake. “Just let me grab my change.”

The sound reverberated in my head like a microphone screeching with audio feedback.

“Dude, you got a fifty-seven on your last math test. You think I trust you to figure out your own change?”

I could see immediately that it was embarrassing to him. I handed Cassie her change and then counted out his nineteen bucks, slowly. Deliberately. Then someone pushed him out of the way and I didn’t see him until later that afternoon.

I had a study period before gym. Instead of wandering to the library as usual, I found one of three spots normally unoccupied by people, in a hall just outside the computer lab.

I pulled out some blue chenille yarn and started crocheting a mati.

The mati was the first thing I’d ever learned to make. It’s a black circle in a blue circle surrounded by a white circle. An eye that Greeks put up to keep the devil away. To ward off bad luck. I was going to leave this one at Yia Yia’s grave. I put all my focus into making small, even stitches, even though I totally heard Drake when he walked up to me.

I ignore people when I’m focused. Especially since my mind was still running from the Snack Shack incident. In the grand scheme of things, it’s just one guy being kind of a dick. But anxiety, remember? Sometimes small stuff hits big.

“Hey, man, that was kinda messed up what you did today.”

I didn’t even look up. Didn’t even try to acknowledge him. Until he pulled my yarn out of my hands.

That’s when I lost it.

I didn’t hit him, but I did lunge forward and swipe for my yarn, which he was holding near his face, and since it probably looked like I was going to hit him, he hit me first. In the face.

In movies they make it look so easy for the hero to get beaten to a gross, bloody pulp and then instantly get back to fighting, but they underestimate pain. Or maybe it’s just that my soft, squishy body could not deal with the slow-motion bulldozing from Drake’s fist.

He is way faster and bigger and stronger. He probably didn’t know what to do when he actually knocked me down. But he did run for the nurse. And even before I hit the ground, I knew my lip would be a meaty disaster. I can only hope the blood that pooled around my body scarred him for life. But then I passed out.

Being unconscious at the time, I can’t really know for sure.

The janitor was the first person I saw when I woke up. I heard him mutter something about the mess he had to clean up.

Nice.

There were no other witnesses. It was just me and my rap sheet of other incidents that labeled me as a problem, even though all those other incidents were bad stuff happening TO me.

Guess they read that as bad stuff happening BECAUSE of me.

Because I mostly just want to be left alone, and for some reason that makes other guys with nothing better to do go, Let’s piss on his backpack and see if he notices.

The best part was when the principal called my dad in to talk. It wasn’t my first time being called in to the principal, but it was the first time in high school. And since I’m a junior now, I’m a little surprised it took this long.

Middle school was another story, though. It had been a shitstorm of counselor visits and principal interventions that never seemed to end because people (i.e., other kids) always want to get a reaction from the Quiet Kid, even when the Quiet Kid isn’t bothering anyone.

I couldn’t hear the beginning of the conversation through the door, but eventually I knew it wasn’t going well when Dad started muttering loudly.

In Greek.

Translated, this is what he said: “What he needs is to stop acting so sensitive and misunderstood. He needs to learn how to deal with people. Or at the very least, how to defend himself.”

“Why did this happen?” Dad finally said in English.

And the next part I heard clear as a bell. So did everyone else in the administration office, because the principal had been trying, without success, to speak over my dad’s muttering, and he forgot to use his inside voice.

“Leo doesn’t get along with his peers!”

The secretary behind the counter jumped a little, then looked over at me and pretended nothing had happened. I had to guess all the other things the principal was probably telling my dad that he already knew, though, because he lowered his voice again.

Things like:

Leo doesn’t play well with others.

Leo doesn’t participate in any school activities.

Leo keeps to himself.

Leo struggles with group assignments and presentations.

Leo knits a lot.

That last one is when my dad would have died of shame.

Even though Yia Yia was his mom. She taught me to knit. She basically taught me how to do anything and everything with yarn and most fibers, and he will never forgive her for it, because it’s not something men do. Well, it’s not something they’re supposed to do.

“This might help you relax, agapi mou,” Yia Yia said.

It is relaxing, but I probably shouldn’t have been doing it at school.

I shouldn’t do anything that draws attention. I shouldn’t do anything I have to explain, because then I invite people in. It’s like asking them to comment on something I enjoy.

Like a guy riding a unicycle down the street. Maybe leave him the fuck alone.

Ride your weird one-wheeled human conveyance machine, dude.

Anyway, that’s what happened.

I got into a fight with Drake, and my dad had to come get me from school. He drove me home with a tissue shoved up my nose, and neither of us spoke the entire ride, which wasn’t unusual, since we don’t speak much anyway.

But there was a moment when the principal asked me what happened and I didn’t say anything about how I’d swiped at Drake first. I didn’t say that it had been a preemptive strike.

I just said: “He hit me.”

Which, like I said, wasn’t a lie, but it wasn’t really the whole truth either. And you can always feel those kinds of lies when they sneak out. Like they’re hiding under your tongue, just waiting for the opportunity to escape.

Now I have to meet with Drake in the guidance counselor’s office to work through our differences, because even though Drake punched me, the principal was clearly concerned about my knitter/loner/quiet-kid label and wanted someone to keep an eye on me.

So, yeah, Drake was a douchebag, but maybe I could have handled it differently, maybe, if I hadn’t gotten so defensive.

Maybe I wouldn’t have said that.

Maybe I could’ve been nicer.

Fuck. How did this happen?

2

Dear Journal,

Jesus, I’m writing in a journal. One step up from talking to myself. I can’t believe this is my life now. I can’t believe this is what happens after a fight.

Generally a fight will get you detention. And maybe a black eye if you’re lucky.

It doesn’t trap you in a room full of people who start every class by thanking everyone for showing up to “share our energy on this magnificent journey.”

Because now I’m here in this yoga class where I am forced to keep this journal to track my progress.

But wait. It’s not just yoga. It is HOT yoga.

Really absurdly HOT yoga that, miraculously, has not yet turned my body into beef jerky despite the fact that I am completely drained of all liquid because it has seeped out of my body.

My eyebrows are filled with sweat, and my underwear has become a bucket for the slip-and-slide that is my butt crack.

This is a series of events I was not prepared for.

But how did I get here?

Oh yeah.

Because after the fight, my dad decided I needed to learn to defend myself.

It’s his most recent attempt to make me a man. Like an actual man. Not a shrimpy, artsy, knitting elf child who dabbles in photography.

He didn’t actually call me those things, but he has this look he gives me, and believe me, that’s what the look says.

But he is the one who uses the word dabbles when he talks about my photography, because he doesn’t want me or anyone else to confuse it with something that makes money. Or something that matters.

Guess it only mattered when Mom did it.

Photography. Cameras. That was Mom. The only memory I have that’s real and not based on a story from Yia Yia is one of me holding Mom’s camera and her teaching me how to shoot.