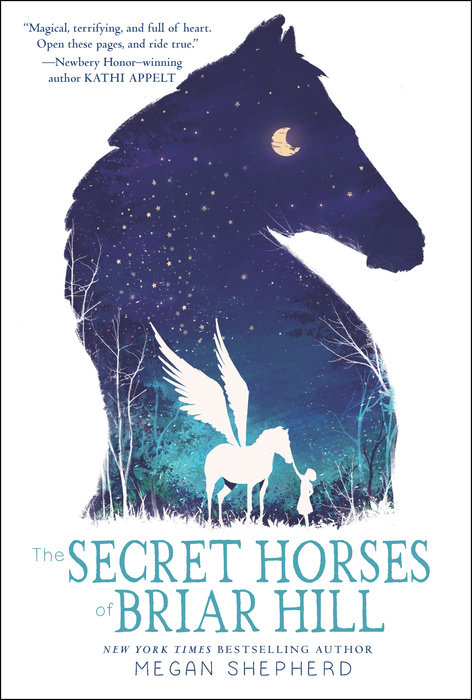

The Secret Horses of Briar Hill

"Deserves a spot on the shelf next to the most beloved children's classics—yes, even The Secret Garden." —Shelf Awareness, Starred Review

Described as "reminiscent of the Chronicles of Narnia" in a starred review, The Secret Horses of Briar Hill shows readers everywhere that there is color in our world—they just need to know where to look.

There are winged horses that live in the mirrors of Briar Hill hospital—the mirrors that reflect the elegant rooms once home to a princess, now filled with sick children. Only Emmaline can see the creatures. It is her secret.

One morning, Emmaline climbs over the wall of the hospital’s abandoned gardens and discovers something incredible: a white horse with a broken wing has left the mirror-world and entered her own.

The horse, named Foxfire, is hiding from a dark and sinister force—a Black Horse who hunts by colorless moonlight. If Emmaline is to keep him from finding her new friend, she must surround Foxfire with treasures of brilliant shades. But where can Emmaline find color in a world of gray?

A Kirkus Reviews Best Book of 2016

"Endearing characters, metaphors for life and death, and a slow revelation of the horrors of war give this slim novel a surprising amount of heft."—Booklist, Starred Review

"In clear, gripping, flawless prose . . . this exquisite, beautifully illustrated middle-grade novel explodes with raw anguish, magic and hope, and readers will clutch it to their chests and not want to let go."—Shelf Awareness, Starred Review

"Reminiscent of the Chronicles of Narnia, Elizabeth Goudge, or a child's version of Life of Pi. . . . Readers will love this to pieces." —Kirkus Reviews, Starred Review

"Magical, terrifying, and full of heart. Open these pages, and ride true."—Newbery Honor-winning author Kathi Appelt

"A remarkable book. Astonishing!"—Michael Morpurgo, author of War Horse

An Excerpt fromThe Secret Horses of Briar Hill

1

I have a secret.

I won’t tell Benny and the other boys. They are like dogs in the night, snarling at anything that moves, chasing cats along country roads just for the thrill of watching them run. I won’t tell Anna, either, even though she is nice to me and shares her colored pencils, even the turquoise one that is her favorite because it reminds her of the sea near her home. Sister Constance tells me that Anna could die soon, and I should be careful and quiet around her. Around Anna I have to tiptoe, I have to pretend that everything is okay, I have to keep secrets to myself.

But I’ll tell you.

This is my secret: there are winged horses that live in the mirrors of Briar Hill hospital.

2

Anna is asleep again.

I lie on the foot of her bed so that I won’t wake her, drawing on the backs of the war pamphlets Sister Constance keeps in a stack by the fireplace for the groundskeeper, Thomas, to use as kindling for the wood he has chopped. There is a gilded mirror above Anna’s chest of drawers. It reflects the mirror-me. The mirror-Anna, snoring. The mirror-room, with its wool blankets strung over the window to hide our lights from outside at night. And, standing in the mirror-doorway, is a winged horse that isn’t in Anna’s room at all. The mirror-horse is nosing through the half-finished cup of tea that Anna left on her bedside table. He has a soft gray muzzle that is beaded with droplets of tea, and quicksilver hooves, and snow-white wings folded tightly. It’s hard to capture with a pencil how horse ears are both round and pointy at the same time.

Benny comes in and sneers at my drawing. His thin red hair, combed back with a wide part down the middle, and his sharp hungry eyes make me think of the rawboned hunting dogs that are always looking for something to make a meal of.

“Horses don’t have horns,” he says.

“Those are its ears.”

“They don’t have wings, either.”

My hand tightens around the pencil. “Some of them do.”

Benny rolls his eyes. “Sure, and Bog is actually a dragon, even though he looks like a flea-bitten old collie.”

Anna wakes, then, and tells Benny to leave, and he does because Anna is the oldest and because she asks him nicely.

“Come here, Emmaline,” Anna says, “and show me what you’ve drawn.”

She wraps her cardigan around my shoulders as I crawl into bed next to her, and gives me a tight squeeze, as snug as if I were home. “What lovely creatures,” she says as she inspects my drawing. “You’ve such an imagination.”

She smiles warmly, but she smells sour, like milk left outside too long. Her face is very pale, except for the places where it is so red it looks chapped, even though it has been many weeks since she has been outside.

I glance at the mirror.

The winged horse has grown bored with Anna’s tea and is backing out of the mirror-room, bumping his rump against the tight angles of the mirror-hallway. I cover my mouth to keep from giggling. Anna can’t see the winged horses in the mirrors.

No one can--only me.

It was late summer when I first arrived at Briar Hill. Sister Constance took me straight to her office and removed the identification tag pinned to my coat. While she made notations in a ledger, I tried to smooth my tufts of hair in the mirror above her desk. Then, completely out of nowhere, completely without warning, a winged horse clomped straight through the mirror-doorway, prim as anything, tail held high, as though Sister Constance’s office were the exact place he was looking for.

“A horse!” I yelled, pointing at the mirror. He was nosing around Sister Constance’s desk. “With wings! And it’s eating your ruler!”

Sister Constance gave me a look like I’d said Winston Churchill was holding a pink parasol while riding an elephant across occupied France.

“There!” I pointed to the mirror again. “Now it’s gotten your pencil!”

She turned to the mirror.

She looked back at me.

She called for the doctor.

Dr. Turner came and felt my forehead, and they spoke quietly to each other by the windows while I tapped my finger against the mirror again and again and again like I used to do with the live fish in the tanks at the fishmonger’s. The horse didn’t turn. He didn’t glance at me at all. He just leaned against the blackboard and fell asleep, while outside Sister Constance’s door, I heard the other children whispering about me.

“Emmaline?” Anna asks. “What are you giggling about?”

I look away from the winged horse with tea on his muzzle. Anna coughs, pressing her hankie to her mouth. Something stirs in my lungs too, still and thick as swamp water. It makes me think of the expression Mama uses when Papa teases me for being sullen. She’ll look up from her book with a smile and say, Leave her be, Bill. There’s mystery in the quiet ones. Still waters run deep.

And this--this liquid, this sickness--there is nothing in the world that could run deeper.

“Emmaline?” Anna squeezes my shoulder.

“It’s nothing.”

Anna hands me back my drawing. With my thick pink eraser, I rub away the ears that I’ve drawn wrong.

“You like horses, don’t you?” she asks. Even with her cough, her voice is gentle.

I blow away the bits of crumbled eraser. I start to redraw the ear. Benny is daft if he thinks it looks like a horn.

“We had workhorses at the bakery,” I say, and add a little tuft of hair coming from its ear. “A big gelding and two bay mares. Spice, Nutmeg, and Ginger. They were beautiful. They had sandy brown hair and dark manes. They wouldn’t ever come when the bakery boys called to them, but they never ran away from me.”

“I guess horses can tell a lot about people,” Anna says.

I look up at her. Her eyebrows are knit together. It is the same look that Sister Constance gets when she goes into the kitchen pantry to take inventory of the dusty cans of ham. There are fewer and fewer of them each week.

“You must miss them terribly,” Anna adds, reaching out to brush back my hair. “I’m sure once you go home they’ll come right up to their stall doors, begging for an apple.” She starts coughing again, but pretends it’s just a tickle, and takes a sip of cold tea. “You can tell them stories about these flying horses in your drawings. Perhaps, long ago, they were cousins.”

I stop drawing.

Anna is looking toward the window, as though something has caught her eye. When Dr. Turner told her she couldn’t leave the bed again, the Sisters pinned back a corner of the hanging wool blanket so that she could have some fresh air. In the hand mirror propped by her bedside table, there’s a flicker of movement. A winged horse is passing by in the mirror-world outside. I can catch only a glimpse of him in the reflected window. He stretches his wings like he’s been asleep all morning. Anna’s eyes jerk toward the mirror. Her eyebrows knit together again, more curiously this time.

Has she seen it?

Has she seen the winged horse?

After that first day in Sister Constance’s office, I haven’t spoken of the winged horses again--except secretly, just a little, to Anna. Everyone else snickers at me behind my back, but Anna would never do that.

And for a moment, as she studies the mirror, I think she might see the horse too.

But then she sighs, and adjusts the barrette in her hair, and flips her Young Naturalist’s Guide to Flora and Fauna open to one of the many dog-eared pages. She looks up, giving me one of her warm, soft Anna smiles. But she can’t muffle her cough with a handkerchief this time. It makes the whole bed shake.

3

Sister Constance has made a new rule. It happened after Benny found one of the chickens torn apart just after breakfast. He came screaming into the kitchen with the dead bird, making its dead wings flap, shaking its dead head, sending Sister Mary Grace into the pickling room in tears. Sister Mary Grace is the youngest nun, in charge of cooking and cleaning. She’s not that much older than Anna, and Anna would cry too, if she saw a dead, bloody bird. Then Sister Constance scolded Benny and told Thomas to bury the bird in the grassy patch of land behind the barn, while she drummed on a tea tin at lunch to get our attention.

“No children are allowed beyond the kitchen terrace, on account of the foxes,” she said.

But after lunch, I sneak beyond the terrace anyway.

I want to watch Thomas bury the bird. The others are scared of him, though he is only twenty--barely a man. Benny says he is a monster. But Sister Constance says God gave Thomas only one arm for a reason, and that reason was so that he couldn’t go fight the Germans like the other young men in the village, so that he would stay here with us, in the hospital, and take care of the chickens and the sheep and the turnip patch, so that we would have vitamins to keep us strong. I know that Sister Constance can’t lie because she’s a nun, but, sometimes, I’m scared of Thomas too. Which is why I hide behind the woodpile while I watch him bury the dead chicken.

It’s the start of December, and the ground is hard, and it must be difficult for him to dig with one arm, but he manages. Where the other arm should be there is only a sleeve fastened to his shoulder with a big silver diaper pin. He lays the dead chicken in the hole. When he thinks no one is looking, he runs his fingers over the chicken’s white, white feathers, and I wonder if it feels the same on his fingers as it would on mine, if soft feathers feel the same for Benny and Anna and Sister Constance and Thomas and me, or if it’s only beneath my hands that chickens feel warm and alive, like stones left in the sun. Then Thomas buries the bird under red dirt, and the bird is gone.

4

Dr. Turner comes every Wednesday to administer our medication in the little room that was once a butler’s pantry. “Tell me how you are feeling, Emmaline,” he says kindly. Everything about Dr. Turner is kind. The way he warms his stethoscope before he presses it against my skin. The chocolate squares he slips me when Sister Constance isn’t looking. The wink he gives me with his woolly gray caterpillar eyebrows.

Dr. Turner is like Thomas: He isn’t whole. Only whole men can go to war to fight the Germans. But what Dr. Turner is missing isn’t an arm or a leg or even a finger. It’s a part of his heart. It’s the daughter and wife he lost to the bombs. The missing part that makes him twitch when there is a thunderstorm, and that one time, when lightning struck the roof and he crawled under the kitchen table and made a strange whining sound like a dog, until Sisters Constance and Mary Grace coaxed him out with weak tea, and sweat was soaking into the armpits of his white coat.

Dr. Turner puts the end of his stethoscope on my back and listens while I breathe. Lining the room, the shelves that used to hold fancy plates are now filled with pill bottles and iodine swabs and tongue depressors.

“Are you taking your medication, Emmaline?”

In the full-length examination mirror behind him, a winged horse is scratching its ear against the window frame.

“Yes, Doctor.”

He frowns as if he might not believe me, and then pulls out a pad of paper and a pencil that he wets on his tongue. He turns his back to lean on the cabinet while he writes, and I make a face at the horse; it keeps on scratching its ear. I wonder what it sees, when it looks through the mirror, back at me. I wonder if the mirror-world feels any different from ours: if, over there, cold is still cold, and hot is still hot, and if Sister Constance’s rulers really taste as good as the horses make them look.

Dr. Turner finishes writing, folds the note in half, and hands it to me. “Give this to Sister Constance to take to the chemist in Wick.”

“Yes, Doctor.”

“And paste this outside your door. I noticed the last one fell off.”

He hands me a blue ticket. He uses the tickets so the Sisters will know what treatment we need each week. There are three colors: Blue for patients who are well enough to go outside for exercise and fresh air. Yellow for those who must limit their activity to indoors. Red for the ones--the one, because it is only Anna--too ill to leave their beds.

Dr. Turner starts to leave, distracted, and I clear my throat loudly so that I’m sure he will hear. He pats his jacket pocket. “Ah. Almost forgot.” He hands me a chocolate wrapped in tinfoil, just like the soldiers get in their ration packs. “Our little secret, yes?”

I smile.

I am very good at secrets. I haven’t told anyone about the time I saw Jack peeing on a hedgehog by the woodshed, and he let me play with his Lionel steam engine if I stayed quiet.

Well, now you know, but you can keep a secret too. I can tell.

Dr. Turner consults his list. “Send in Kitty next.”

I slip off the examination table and pop my head into Sister Constance’s classroom, where she is giving the little ones their spelling lesson, to tell Kitty it’s her turn. Then I march down the hall. We older children don’t have our lessons until the afternoon, so my time is my own, for a little while at least. The mirrors here are empty, but the floors shake, and I wonder if winged horses are walking down it in their world behind the mirrors, or if it is just Thomas banging around on the furnace below. I match the thunk-thunk-thunk with my steps until I reach the narrow staircase. I peek over my shoulder for any wild-dog boys with parted red hair. Clear. I dart up the stairs, past the residence level, then up again toward the attic, start unwrapping Dr. Turner’s chocolate, and I am just about to take a bite when a face jumps out of the shadows.