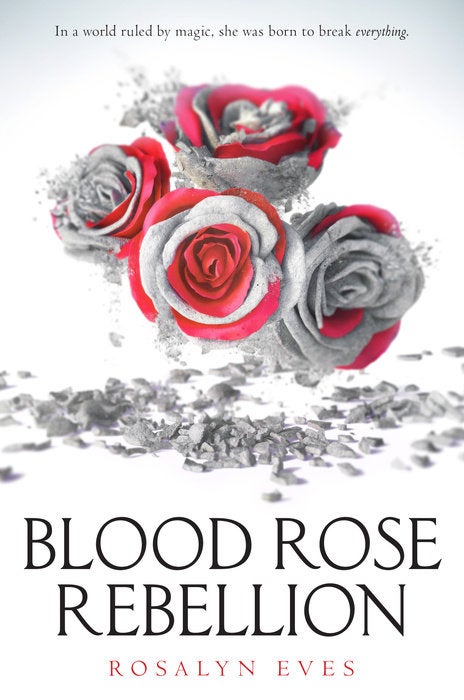

Blood Rose Rebellion

An Excerpt fromBlood Rose Rebellion

CHAPTER 1

London, April 1847

I did not set out to ruin my sister’s debut.

Indeed, there were any number of things I deliberately did not do that day.

I did not pray for rain as I knelt in the small chapel of our London town house that morning, the cold of the floor seeping into my bones. Instead, I listened to Mama’s petition for successful spells and sunshine. Peeking through my lashes at Catherine’s smug face, I yearned to ask for disquiet, disorder, and torrential downpours--calamitous words that might have eased, a little, the restless crawling in my heart. But I swallowed the words unsaid. Even should God heed such a treacherous prayer, my father would not. Though Papa’s weather magic would cost him a headache, my sister would dance under clear skies.

I did not argue with Catherine when she banned me from the ballroom where she and Papa laid the final grounding for her illusions while Mama supervised the servants. “You’ll break my concentration and spoil my spells,” she said, though it had been years since I had spoiled anyone’s spell, accidentally or otherwise.

But then I did not go to the schoolroom, where I was expected to improve my sketching while my brother, James, studied his Latin. Instead, I lingered (Mama would say loitered) in the lower hall, watching the servants scurry back and forth with their brooms and buckets and cleaning cloths, in feverish preparation for the ball. I did not rest, as Catherine did.

Because of those omissions, I was in the hallway when Lord Frederick Markson Worthing came calling. I heard Freddy’s signature knock--two short, three long--and my heart leapt.

Barton reached the door first and sent me a cross look down his long nose. He accepted a small white visiting card from Freddy, and I slipped into the open doorway.

“Lord Markson Worthing!” I smiled up at him, remembering just in time to use his formal name. “Won’t you come in?”

I didn’t have to look at Barton to know his brows were lowering. Our butler disapproved of forwardness in general and of me in particular.

Freddy returned my smile, his gloved hands tightening around the bouquet of roses he carried. “Thank you, Miss Anna. Only for a moment. I don’t want to leave my horses standing too long in this wind.” In truth, Freddy had no need for horses. As a Luminate of the order Lucifera, he could compel the carriage with spells. But he preferred the aesthetic of his matched bays, which drew the eye and required less effort to maintain than magic.

Barton led us upstairs to the Green Drawing Room, so named for the ivy pattern sprawling across the wall and the deep emerald drapes. “I will notify your mother, Miss Anna.”

Freddy and I sat on matching high-backed chairs near the window. Freddy leaned toward me, nearly crushing the roses he held. He smelled of tobacco and cinnamon.

“I hoped I might see you.”

My face grew warm as I met Freddy’s intent gaze. I had first encountered Freddy only a few days after we arrived in town for Catherine’s season, to launch her into Luminate society. As the son of an old school friend of Papa’s, he had come to pay his respects. But though he had talked to Catherine, he had looked at me. Two days later, our paths crossed by accident in Hyde Park, and after that, by design. My maid, Ginny, might suspect the frequency with which Freddy appeared during our errands about London, but she was the only one who knew of our involvement.

There was no one in the world I liked so well as Freddy. I admired the way his honey-colored hair curled a little above the collar of his coat. I adored his eyes, which were not really grey but a band of blue around a center of brown. And I loved him for the way the corners of his lips trembled when he was impassioned: when he spoke about his plans for a seat in the Luminate-led Parliament, or his dreams of a salon in London where Luminate could mingle freely with artists, poets, politicians, and scientists, where wit would trump magic, and ideals would matter more than money.

There was little room in the real world for people like me, but there might be room in Freddy’s. We would be a good match, equals in passion and intelligence. I would bring the money his family lacked; he would provide the magic I lacked.

“I have something I want to say to you. Will you be at the ball tonight?”

“I am not yet out,” I reminded him. And Mama does not trust me around magic.

“Then meet me. In the herb garden, at midnight.”

The heat in my cheeks deepened. I rearranged my skirts, pretending a composure I did not feel. “Very well.”

“Good girl.” Freddy stood then and adjusted his top hat. “I must go.” He thrust the flowers at me, roses of a red so deep their centers were almost black. The petals spilled over my fingers like blood.

I watched him walk away, admiring the straight line of his back. In the doorway, Freddy spun around to face me. “The flowers are for Catherine. See that she gets them, will you?”

“Anna?” Grandmama stood in the doorway, her fingers tight around her cane. “Has Lord Markson Worthing gone already?”

I looked up from the flowers. “He couldn’t stay. His horses were waiting.”

“And you were alone with him this entire time?” Her mouth was pursed, her Hungarian accent more pronounced. First Barton, now Grandmama. At least Grandmama’s disapproval stemmed from affection.

My shoulders lifted a little. “He left these for Catherine.” I held out the roses and wondered if Grandmama would guess how much hid behind that small truth. Though it was customary to bring flowers to a debutante, I could not fathom what Freddy meant by asking me to meet him at midnight but leaving me with my sister’s roses.

“Do not shrug. It is not ladylike.” Her dark eyes studied my face, guessing at my discontent. “And do not pine so for Luminate society, for the magic and the dancing. You are enough just as you are--and you are not yet seventeen, szívem. Your turn will come.”

“Mama would hide me in the country if she could.”

“Your mama loves you. She is afraid for you, is all.”

I did not believe that. Mama was afraid of me, of my strange lack of magic and my caprices. My fingers found a missed thorn on one of the roses, and I snapped it off.

Grandmama sighed. “Give me those flowers. I will take them to Catherine. You should go upstairs before your mama finds you.”

I relinquished the roses, but their scent followed me down the hall like a promise.

I sat on Catherine’s bed, hugging my knees to my chest. As children, we had often sat on Mama’s bed, watching Mama transform through the artifice of her maid from an ordinary mother into something resplendent and strange. I did not know if Catherine was thinking of our old habit when she summoned me or of flaunting her debutante status.

Catherine’s maid attached a small coronet of pearls to my sister’s mahogany hair. Catherine surveyed her reflection in the ornate mirror, smiling at the effect. Her image seemed unfamiliar, her usual severity softened by the glass and the late-afternoon light. Behind her, I could see the smaller circle of my face, a pale smear of flesh with dark holes for eyes.

I disliked mirrors. Sometimes when I looked at them aslant, I caught an uncanny doubled image, as if I were not one person but two--as if I were a stranger in my own skin. I never knew if such reflections were a by-product of my lack of magic or merely a defect in my vision.

Catherine must have seen something in my look to distrust, because she whirled suddenly. “Anna, you will be good, won’t you? You know how much tonight means. I have worked so hard for this moment.”

I did know. Catherine was almost frightening in her single-mindedness, and the only thing she wanted more than a dazzling marriage was a position in the Circle, the elite group of Luminate who governed all magic. If her debut spells were suitably impressive, she might be invited to apprentice with one of the Circle members, lifting her into the highest echelon of Luminate society.

“What would I possibly do? I won’t be anywhere near you.” Except at midnight, in the gardens.

“Strange things happen around you. You’re so very . . .” She paused, searching for the right word.

“Quixotic? Unconventional? Immodest?” All those, and worse, had been hurled at me by exasperated governesses in the past.

Her brows drew together, a faint tuck of disapproval. “You’ll never get a husband with that attitude.”

“Perhaps I don’t want one.” My eyes dropped to the soul sign glimmering above Catherine’s collarbone: the illusion all full-blooded Luminates learned to craft upon entering society, evidence of their magic, just as their jewels witnessed their wealth, and their titles their lineage. Hers was a white rose with fire in its heart. I thought of the sign I would craft, if I could: a peregrine falcon, perhaps--fierce, swift, and strong.

Catherine could not know how galling it was to live in our world as I did. Every noble-born came into their Luminate magic after their Confirmation at age eight--except me. Without magic, everything about me was suspect: my lineage, my quality, my education, my very self. I had no hope of belonging to Luminate society unless I could marry into power, but as Mama frequently pointed out, no one of any position would choose someone so flawed. I would have no fancy debut, as Catherine would, because it would serve no purpose. Yet my noble blood barred me from seeking an occupation among commoners unless I wished to cut myself off from my family.

Until Freddy, I had not realized I might have a future.

My sister ran her fingers along the rim of the cut glass vase now holding Freddy’s roses. “Lord Markson Worthing will be there. He has been so attentive lately.” She glanced at me from under her eyelashes, a demure trick I could never hope to master. “I know you like him, Anna. But you should understand he would never look at you. Not seriously. His father intends him to marry me.”

My hands curled tightly on the coverlet of Catherine’s bed. What was it Freddy wished to tell me? That he loved me--or that he meant to court Catherine? I did not think I could bear it if he married her. She only cared for his name and his title and his family.

She did not deserve him.

At ten minutes to midnight, I set down my book of poetry and smoothed the sleek coils of dark hair around my ears. As a treat, James and I had been served some of the supper dishes in the schoolroom: lobster, dressed crab, rice croquettes, tongue sliced so thin it was almost transparent, pastries, cheeses, pulled bread, and iced pudding. James had eaten himself into a stupor and was now snoring on the rug, a book of fairy tales long forgotten beside him. I covered him with a quilt and crept down the stairs to my father’s library.

I hesitated in the doorway, listening. Were I an Elementalist like Papa, capable of manipulating wind and light, I could set a spell on the air to tell me whether anyone lurked nearby. As it was, I had to rely on my own senses. Beneath the distant echo of voices and music, I heard only the quiet spit and crackle of fire in the grate, so I plunged into the room, crossed the carpet, and pushed my way out the large French doors into the garden.

A gentle breeze caressed my cheek, part of the wind charm Papa used to keep the smoke and fog of London from our garden. I closed my eyes and took a deep breath, smelling green and growing things. After the threatening sky of the afternoon, the evening had come on clear. Papa did not often use his magic, but when he did, his handiwork was always finely wrought.

I followed a little-used path toward Grandmama’s herb garden. I loved her garden, especially in summer when the air was sharp with mint and basil. Even in winter I loved it: the bare, orderly plots waiting for spring, the neat circular walkway around the center.

The garden was empty when I arrived. The darkness of the night crept up my arms, settled under my heart. Freddy was not here.

A gust of wind brought with it the scent of roses from the ballroom, and I shivered. Perhaps Freddy was having difficulty getting away or negotiating the garden in the darkness.

Footsteps crunched on gravel behind me. My heart thumped, and I crouched down below the shadow of the hedge. I could not be seen. I was not supposed to be here.

A man’s low voice sounded; it was not Freddy. “There’s fighting again in Manchester, bloody lower classes demanding access to magic. Why can’t they simply accept the order of things? If they were meant to have magic, they’d have been born Luminate. There’s no magic in common blood. Riots and petitions for magic will not change that.”

A pause, then a second voice. “The commoners questioning is bad enough. But they say Arden is a heretic, wants to do away with the Binding.”

“Madness. How can he not see that breaking the Binding will undo the very social order that supports us?”

The hair at the nape of my neck lifted. Why should these men link Papa with the worker riots? He was no heretic. He believed in the sanctity of the Binding, the great spell that held all magic in a vast reservoir of power, accessible only to those with Luminate blood.

“So I’ve heard. But his younger daughter’s Barren and his son’s nearly so. What more would you expect from such a family?”

“The elder daughter is comely enough. I hope for her sake her blood runs truer than her sister’s.”

My cheeks burned as the voices muted, moving out of range. I tried to push the conversation from my mind. I hated that people could speak so casually of my family, dismissing us--me--as so much gossip.

A fresh wind plucked at my hair and sleeves, and I smelled tobacco and cinnamon. My heart lifted; Freddy had come. I straightened and turned to face him. I was tall for a girl, nearly of a height with Freddy.

He took my hand, linking my cool, gloveless fingers with his gloved ones, and led me to a bench. “I’m sorry I was late. I was held up talking with Lady Dorchester.”