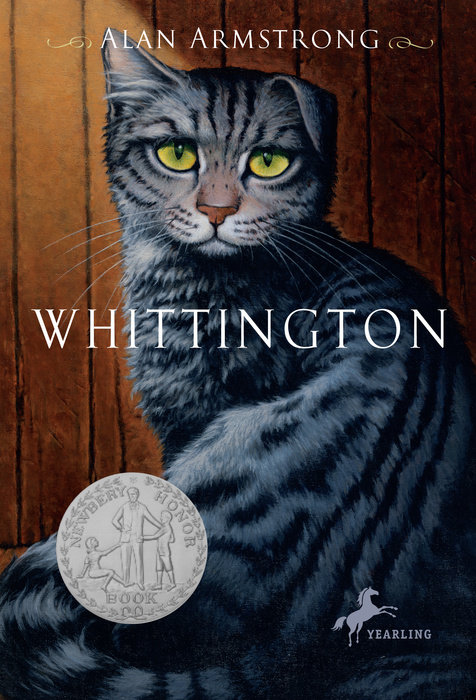

Whittington

This Newbery-Honor winning tale introduces Whittington, a roughneck Tom who arrives one day at a barn full of rescued animals and asks for a place there. He spins for the animals—as well as for Ben and Abby, the kids whose grandfather does the rescuing—a yarn about his ancestor, the nameless cat who brought Dick Whittington to the heights of wealth and power in 16th-century England. This is an unforgettable tale about the healing, transcendent power of storytelling, and how learning to read saves one little boy.

An Excerpt fromWhittington

10

The Man Whittington Named Himself After

Bernie had to leave while he could still get the truck up. The kids wanted to stay. He said okay. Abby had a watch; he’d collect them at three by the highway.

They could hear the storm. The wind sent flakes in through the cracks and the broken-out window up top. Ben shivered. The Lady had the kids pull down fresh hay. It fluffed up and smelled like summer. She made the horses lie down close together and had the kids snuggle next to them. She settled herself on one fluff, Couraggio on another. The bantams made a show of flying up to the rafters and perching where they could look over everything in comfort.

The cat was full of tuna. He wanted to lie down in a warm place too. The Lady told him to get up on the stall railing where everybody could see him.

“Now go on with your story,” she said.

“Story? What story?” the kids chorused.

Whittington shook himself. “This is the story of rats and the cats that hunt them. Rats carry the fleas that carry plague. Plague makes your groin and underarms swell up and your tongue turn black. You get buboes and spots and foam at the mouth and die in agony. It’s called the Black Death.

“Dick Whittington’s cat won him a fortune because she was a rat-hunter. Centuries before they figured out what plague was and how it spread, people knew that a good rat-hunter could save your life.

“The man I’m named for was born about the time the Black Death hacked through England like a filthy knife. By the time he was five years old a quarter of his town was empty. It was a horrible loneliness.

“His family was poor. The soil was thin and ill-tended. There wasn’t enough food. There were no schools. The grandmother who lived with his family taught him to read. The priest had taught her. There were no printed books. She copied out things on scraps of stiffened cloth and scraped animal skins called parchments. She wrote down remedies, recipes, family records, and Bible passages the priest taught her.

“She smelled of the oils, herbs, and mint she used in the remedies she made. She was a midwife and a healer, one of the cunning folk they called her. The priest taught her reading and writing so she could copy recipes for remedies and keep the parish records. Dick gathered simples for her. He had a good eye. That was his work. Other boys his age picked stones from fields, gleaned corn, scared crows, drove geese. If you were idle you didn’t eat.”

“What are simples?” the Lady wanted to know. The kids nodded. They didn’t know either.

“Plants,” the cat said. “They made medicine then from leaves and blossoms, sap, roots. Dick’s grandmother boiled and ground plants into ointments and syrups to heal people.”

“We fowl do that,” the Lady said, looking at Couraggio. “When we’re ill we know what to eat to get better.”

“We do too,” said Abby. “When we’re sick to the stomach Gran makes tea from the mint that grows around and stuff for hurts from tansy, the plant with yellow button flowers.”

“For colds she makes yarrow tonic and rose-hip paste,” said Ben. “She puts honey in the tonic. The rose stuff is bitter.”

“When I’m sick I eat new grass,” the cat said.

“Okay,” said the Lady. “Go on with your story.”

“Dick was always surprised how warm his grandmother was when they sat close together. She read aloud the same things over and over, leading with her finger as she sounded out the letters. What he read to himself at first was what he remembered hearing as he followed her hand. He’d mouth the words as he went along, sounding them out. Not many of his time knew how to read and few of those learned silent reading. He was a mumbling reader all his life.

“One afternoon in the village he saw a gold coin. He’d been loitering around a stout stranger hoping to perform some service and earn a tip when the man went into the baker’s. Dick followed him in and watched as the stranger bought a halfpenny’s worth of bread. The stranger got three round wheat loaves, honey-colored and heavy. He stuffed two into his coat and gave one to the boy. The man fumbled in his purse for a coin. He held it out for Dick to see. It was the size of a fingernail, stamped with a face. It gleamed like nothing Dick had ever seen before. What impressed him almost as much as its gleam was how carefully the baker studied it and weighed it and how many coins he gave in change.

“Then one day outside the inn he overheard a carter telling the men helping him unload barrels of cider that he had heard from a man who had been there that London’s streets were paved with gold and all the people were plump and healthy.

“That night Dick had a dream. He dreamed he went to London and became the stout stranger, filling his purse with the small gleaming rounds of gold that lay like pebbles in the streets. He went to the baker and stuffed his pockets, he went to the inn and was served roast meat and cider. In his dream he was never hungry again. He wore warm clothes and was never cold again either.

“He had heard talk that he was to be put in service to a tanner, a hard man who beat his boys and fed them poorly. Working with hides was a dirty, stinking business. The boys had to scrape off rotting flesh and hair and lift the heavy skins in and out of the tanbark vats. A boy in the tanner’s service had hawked up blood and died. Dick figured he’d better get out on his own pretty quick.”