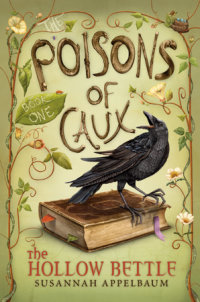

The Poisons of Caux: The Hollow Bettle (Book I)

The Poisons of Caux: The Hollow Bettle (Book I) is a part of the The Poisons of Caux collection.

Introducing a witty and macabre new fantasy trilogy.

There's little joy left in the kingdom of Caux: the evil King Nightshade rules with terrible tyranny and the law of the land is poison or be poisoned. Worse, eleven-year-old Ivy’s uncle, a famous healer, has disappeared, and Ivy sets out to find him, joined by a young taster named Rowan. But these are corrupt times, and the children—enemies of the realm—are not alone. What exactly do Ivy and Rowan’s pursuers want? Is it Ivy’s prized red bettle, which, unlike any other gemstone in Caux, appears—impossibly—to be hollow? Is it the elixir she concocted—the one with the mysterious healing powers? Or could it be Ivy herself?

Told with wry humor, The Hollow Bettle is the first installment in the Poisons of Caux trilogy, an astonishing tale of herbs and magic, tasters and poisoners.

An Excerpt fromThe Poisons of Caux: The Hollow Bettle (Book I)

Mr. Flux Arrives

It’s an astonishing feat that young Ivy Manx was not poisoned during Mr. Flux’s tenure as her taster.

These were corrupt times in Caux, the land being what it was—a hotbed of wickedness and general mischief. The odds were stacked against anyone surviving their next meal, unless they had in their employ a half- decent Guild-accredited taster. A taster such as Mr. Flux maintained himself to be.

The day of Mr. Flux’s arrival was a day like any other, devoid of goodwill and cheer (and befitting the taster’s disposition). A fire burned glumly in the grate within the small tavern Ivy called home, and beside it a few disinterested regulars took their drinks in tedious silence. Hidden in her secret workshop, Ivy Manx found herself hoping for something thrilling to happen—perhaps a particularly rousing poison- ing. She had been ignoring her studies in favor of one of her experiments when Shoo cawed softly.

“Never you mind,” Ivy admonished the crow. “Cecil will never know I was using his equipment unless you tell him.”

She proceeded to strain an evil-smelling mixture through her uncle’s sieve. Ivy worked with a look of great concentration upon her face, and when the task was finished, she set the vessel on a burner to boil. Almost immediately the syrup discharged a clingy cloud, and a sickly sweet smell filled the small room, forcing the crow to alight dizzyingly on a coatrack to avoid it.

This was greatly disobedient, she knew. Her uncle wished her to be a learned apotheopath—a healer—yet tinkering with her noxious brews was much more satisfying. Like most of Caux, Ivy preferred not the well-meaning herbs, but the darker, more potent ones. Apotheopathy seemed ancient to the ten-year-old, from a time when plants were used to heal, not harm. Her uncle’s collection of dusty books and scribbled parchments made her yawn—both to Cecil’s and Shoo’s great disappointment.

“There. Let’s see what that does when it’s done.”

As she stepped back in the workshop, Cecil’s top shelf caught her eye. He was still in the habit of putting his secrets up high, thinking they remained safely out of her reach. There was quite a lot to see, for as Ivy knew, there is no such better display of a person’s ideals and deficiencies as a bookshelf. (Cecil tended toward being an untidy person and the shelf illustrated this fact well.) Her eyes narrowed at the sight of the small leather case that contained his apotheopathic tinctures.

She pushed over a three-legged stool, and as Shoo grew ever more agitated, Ivy climbed up, reaching.

“Just a peek, Shoo. It’s his remedies. Clearly, this counts as studying.”

The black crow, longtime resident of the Hollow Bettle, knew better. The ampoules were strictly off-limits at this point in her studies, and the crow began pacing excitedly. With her uncle set to depart the tavern in the evening, Ivy was reminded that this trespass would better wait until then.

“But he’ll take them with him,” she told Shoo. “And, if you’re lucky, you, too.”

The stool was proving to be insufficient. Ivy considered climbing up the rickety shelves themselves. She wanted nothing more than to examine the delicate glass-stoppered medicines within the case and had long ago given up asking. First she must complete the long memorizations of herbs and plant lore—so completely bookish and boring.

“Anyone can produce a potion that will make you sick,” her uncle would remind her, his eyes gleaming with enthusiasm. “But it takes much learning to use plants to cure! Which would you rather be, then, a common poisoner or a respected healer?”

Interestingly, Cecil never seemed to wait for an answer.

g

Testing a bowed shelf for sturdiness, she gingerly began scaling upward, with Shoo now flying about the room squawking excitedly.

Ignoring the bird, Ivy was quite nearly there when the worst happened. Her foothold gave way and the entire contents of the overburdened unit—her uncle’s medicinal books and priceless notes, his scales and workshop essentials, important-looking mahogany boxes containing powders and infusions—all came crashing down, nearly taking Shoo with it.

In the silence that followed, Ivy and the crow waited nervously for Cecil’s appearance. Her straw-colored hair and flushed cheeks were streaked with her uncle’s pitch. She brushed something white and gritty from her shirtsleeve while considering what an appropriate punishment would be—and wondered if he’d forbid her from her experiments. (Just how this would be enforced in his absence she wondered, too.) Shoo, rumpling his sleek feathers, settled in front of the narrow door that let out into the tavern area.

“Don’t be in such a hurry. He’ll hold you responsible, you realize.”

When a remarkable amount of time had passed and her uncle had failed to respond, Ivy grew curious.

The workshop door was veiled from sight by dust and shadow, a sly entrance cut in the middle of an enormous blackboard in residence upon the tavern’s far wall. It was further obscured by the simple fact that the shadowy wall was never regarded—the menu on the blackboard was long obsolete. When Cecil was seeing his patients or when the workshop was hosting Ivy’s nefarious experiments, a sharp eye might discern a flickery crack of amber light slicing through the darkness. It was here that Ivy put her eye, wondering what might be keeping her uncle.

It was fortuitous timing. Ivy watched as a scrawny and particularly unimpressive stranger crossed the threshold, pausing right in front of her to scrape the caked mud from his tatty boots. He exuded from him a sour sense of disinterest, and clinging to him, although unseen, was an odd sort of melancholia—the kind that affects the bearer not at all, but those who behold him feel instantly cheerless.

Having just passed through the Bettle’s creaky front door, Mr. Flux—for indeed this was he—made a beeline to the bar. He ordered and consumed an unusually expensive brandy and then quickly ordered another, requesting Cecil leave the bottle before him.

Surveying the room, Ivy gave the lone traveler five minutes in the midst of this group of scoundrels and found herself eager at the prospect of his gruesome end.

“At last,” Ivy whispered to Shoo. “Something exciting.”