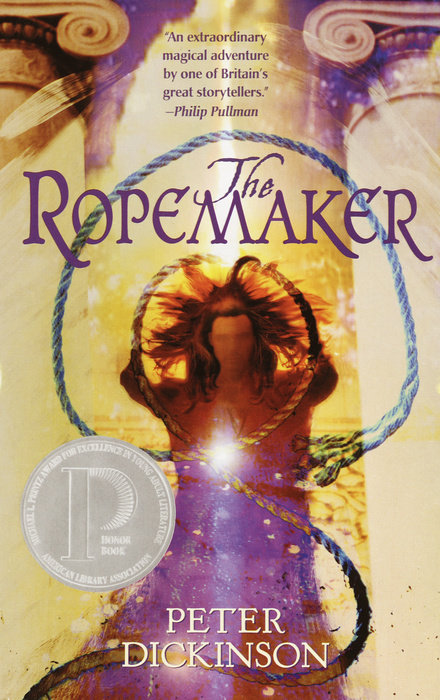

The Ropemaker

The Ropemaker is a part of the Ropemaker Series collection.

Tilja has grown up in the peaceful Valley, which is protected from the fearsome Empire by an enchanted forest. But the forest’s power has begun to fade and the Valley is in danger. Tilja is the youngest of four brave souls who venture into the Empire together to find the mysterious magician who can save the Valley. And much to her amazement, Tilja gradually learns that only she, an ordinary girl with no magical powers, has the ability to protect her group and their quest from the Empire’s sorcerers.

An Excerpt fromThe Ropemaker

1

The Forest

It had snowed in the night. Tilja knew this before she woke, and waking she remembered how she knew. Somewhere between dream and dream a hand had shaken her shoulder and she'd heard Ma's whisper.

"It's snowing at last. I must go and sing to the cedars. You'll have to make the breakfast before you feed the hens."

Tilja reached up to the shelf beyond the bolster and pulled her folded underclothes in under the quilt, where she spread them along beside her body to warm through. While they did so she lay and listened to the wind hooting in the chimney above her. Anja, beside her, grumbled in her sleep, clutching at her share of the quilt while Tilja wriggled out of her nightshirt and into the underclothes. Then she slid out and hurried into another layer of clothing, tucked Anja snugly in and finished dressing.

The bed was a boxlike structure set right into the immense old fireplace, on one side of the stove. Her parents slept in a larger box on the far side, but that would be empty by now, with Da in the byre seeing to the animals, and Ma on her way to the cedar lake, far into the forest.

Faint light seeped through the shutters, but she didn't open them, and not just because of the savage wind that was battering against them and shrieking into their cracks. She liked to do these first tasks in the dark, knowing without having to feel around exactly where to put her hand for anything she needed. Woodbourne was her home, and this kitchen was the heart of it, as familiar to her as her own body. She had no more need to see to find things than she had to put her finger to the tip of her nose. Relighting the stove in the dark was a way of starting the day by telling herself that this was so.

First, she opened the firebox and carefully riddled out the old ash, leaving just the last black embers, flecked with sparks. Onto these she spread a double handful of straw and another of dry twigs, then closed the fire door, opened both dampers, and stood leaning against the still-warm stove while she repeated the fire charm three times. Ma never bothered with the fire charm, but Tilja's grandmother, Meena, had taught it to her so that she would know how long to wait for the twigs to be well alight before she added the coarser kindling. Usually it took four times, but three would be enough with a wind like this to drag the draft up.

A wind like this? And snowing? That wasn't right.

Once the kindling was in, and had caught, she slid in four logs, sawn and split to fit the stove and dried all summer in an open shed. The flames began to roar into the flues. Now at last she poked a taper in and used it to light the lamp, poured water into a pan and set it to boil, heaved the porridge pot out of the oven where it had been quietly cooking all night in the remaining heat from the old fire, stirred in a little water and set it beside the water pan to warm through.

Next she finished getting up. She rinsed her face and hands, combed and bunched her hair and slipped into her boots, leaving the laces loose, and opened the door into the yard. At once the wind flung a gust of snow into her face, stinging as if it had been a handful of fine gravel. Brando was out of sight, cowering in his kennel from the storm.

This is all wrong, she thought again as she clumped across to the outhouse. The first snow in the Valley should have fallen a month ago, on a still night, huge soft flakes floating steadily down, blanketing yard and roofs and fields a foot deep by morning. These furious flurries weren't snow. And nothing was really lying. Any flakes that reached the ground were snatched up by the wind and whirled into drifts in the corners of the yard. When a gust hurtled in from another direction it would catch at these and set them streaming away like smoke.

Worse still, checking by touch in the dark of the outhouse, she found that some of the stuff had found its way in through a crack and made a miniature drift across the seat. With freezing fingers she scooped it away, did what she had to and clumped back in a foul temper to the kitchen. She half thought of sending Anja out with a storm lantern to clear the outhouse and block the crack before Da got back, but in the end she did it herself.

By the time he came in she had the porridge hot and the sage tea brewed and the bacon frying, and Anja was up and dressed and clean.

"Stupid sort of snow we've got this year," he muttered. "I hope your mother's all right."

"Where's Ma gone?" said Anja, through porridge.

"She's gone to the lake to sing to the cedars," said Tilja. "She'll be home to cook your dinner."