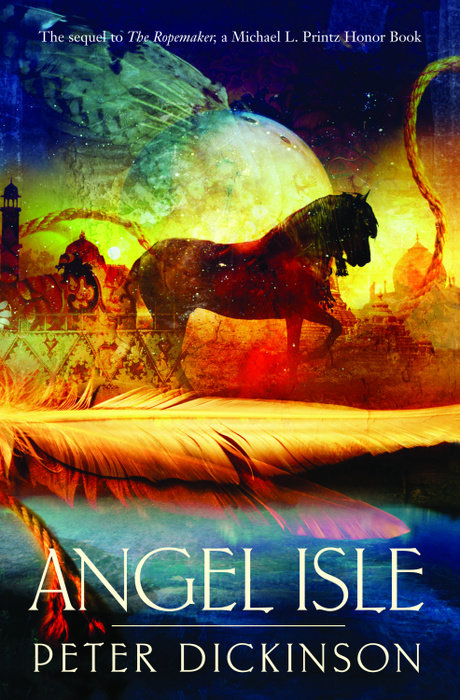

Angel Isle

Angel Isle is a part of the Ropemaker Series collection.

ONCE THE 24 MOST powerful magicians in the Empire pledged to use their magic only to protect the people. But the promise that bound them has now corrupted them. They have become a single terrible entity with a limitless desire for domination. Only the Ropemaker may be able to stop them, but he has not been seen for over 200 years. Into this dangerous world come Saranja, Maja, and Ribek. They seek the Ropemaker so that he might restore the ancient magic that protects their valley. It is the task they were born to, but now it seems there is far more than the valley at stake should they fail. . . .

An Excerpt fromAngel Isle

Cold, hungry, terrified, Maja watched the two strangers from her secret den beside the mounting block, beneath the burnt barn. That was where she’d run when she’d seen a troop of the savage horsemen from the north come yelling up the lane all those days ago, and lain there cowering. Her uncle and the boys were away fighting the main army of the horsemen, but they must have caught her mother and her aunt. Maja couldn’t see what they did to them because of the smoke, but she’d heard their screaming. Then the smoke of the burning buildings had got into the den and overcome her. After that she didn’t remember anything for a while, and when she woke the savages were gone and the farm was ashes around her.

She had felt too ill to move, and too terrified of the savages, and her throat had been horribly sore, but at last she’d crept out and climbed up to the spring and drunk, and then stolen round the farm like a shadow and found her mother’s body and her aunt’s lying face down in the dung pit, and a lot of dead animals scattered around. Her aunt used to make her help with the butchering, so she cut open a dead pig with her knife and roasted bits of its liver on the embers of her home, and despite the soreness of her throat had managed to swallow it morsel by morsel. By the time she’d finished, it was beginning to get dark, so she’d crawled back into her den and curled up in her straw nest and slept there all night without any dreams at all.

She’d spent the next day collecting dry brushwood and straw and the burnt ends of rafters and beams and piling it all into the dung pit on top of the two bodies. As dusk thickened she’d used a still smoldering bit of timber to set the pile alight.

“Good-bye, good-bye, good-bye,” she’d whispered as the flames roared up, then turned away dry-eyed. She didn’t seem to feel anything. She was vaguely sorry about her mother, and vaguely guilty that she’d never learned how to love her. There hadn’t been anything there to love. She’d dreaded and hated her aunt, but her aunt had shaped her world and she felt a far greater sense of loss at her going. Now that shape was shattered and all she had was emptiness, until her uncle came back from the fighting, if he ever did.

The dead animals had soon begun to rot, but some of the chickens were still alive and hanging around because they didn’t know anywhere else to go. There was good barley out in the little barn in Dirna’s field, which her aunt grew there every year to feed to the unicorns, so the chickens learned to come to her again when she called to them, and she managed to coax some of them into laying. She ate the cockerels one by one and found a few things still usable in the vegetable patch and the orchard, and survived, afraid and lonely.

She had found her den long before. Ever since she could remember she had needed somewhere to hide. Hide from her uncle’s sudden, inexplicable rages, from her aunt’s equally savage tongue, from her boy cousins’ thoughtless roughness. Only occasionally did anyone hurt her on purpose. Indeed, once or twice when she was small and at the end of one of his outbursts her uncle had slammed out to the barn, her aunt had deliberately sent her out to call him in, despite her terror of him. It was one of her aunt’s ways of punishing her, though she’d never been told what for. So she’d crept through the barn door, tensed for his anger, but instead he’d called to her and put her on his lap and fondled her like a kitten for a while, and spoken gently to her, though she could feel his rage still roiling inside him—and it was the rage itself that had terrified her, not the fear that she herself might suffer from it. Usually it had been her big cousin Saranja who’d suffered, or the two boys—and they had been always angry too. Even her own mother had been too vague and feeble to notice her much, let alone stand up for her when she needed help. She must have had a father, of course, but she’d never known him, and had no idea who or where he was. She didn’t dare ask. Saranja had been the only person besides her uncle who had sometimes smiled at her, as though she had meant it.

But then there had come the day she had taught herself never to think of, and at the end of it Saranja had gone away and the rage had been ten times worse than before and her uncle had never spoken to her kindly again.

And it was all Maja’s fault. It always had been, even before that. Since she was born.

There was a bit of the heap of ashes that had been Woodbourne which she fed with fresh wood to keep the embers going, and then hid under layers of ash when she’d finished her cooking. She’d just done that when she’d spotted the woman trudging along the lane with an old horse trailing behind her, and a solitary figure limping along further back. They hadn’t looked dangerous, but all the same she’d clucked to the chickens, who’d come hustling over, imagining it was the start of the evening drill that kept them safe from foxes. She’d laid a trail of barley to lure them into the den and lain in the entrance to watch, letting the scorched branch of fig that screened it fall back into place.