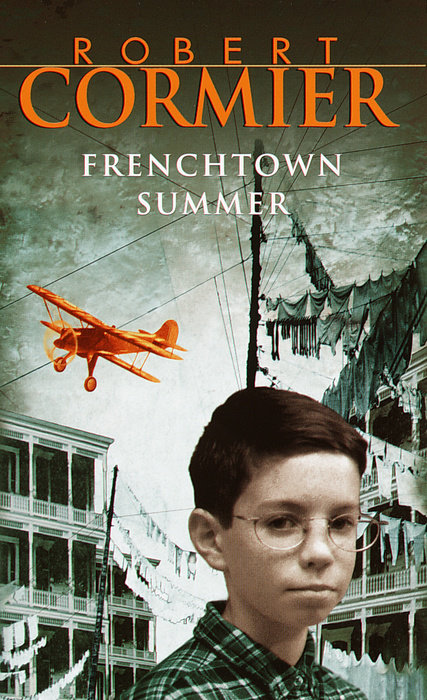

Frenchtown Summer

Eugene is remembering the summer of 1938 in Frenchtown, a time when he began to wonder “what I was doing here on the planet Earth.” Here in vibrant, exquisite detail are his lovely mother, his aunts and uncles, cousins and friends, and especially his beloved, enigmatic father. Here, too, is the world of a mill town: the boys swimming in a brook that is red or purple or green, depending on the dyes dumped that day by the comb shop; the visit of the ice man; and the boys’ trips to the cemetery or the forbidden railroad tracks. And here also is a darker world–the mystery of a girl murdered years before. Robert Cormier’s touching, funny, melancholy chronicle of a vanished world celebrates a son’s connection to his father and human relationships that are timeless.

An Excerpt fromFrenchtown Summer

Doorway Shadows

That summer in Frenchtown in the days when I knew my name but did not know who I was, we lived on the second floor of the three-decker on Fourth Street. From the piazza late in the afternoon I watched for my father, waiting for him to come home from the Monument Comb Shop. No matter how tired he was, his step was quick. He'd always look up, expecting to see me, and that's why I was there, not wanting to disappoint him or myself.

That was the summer of my first paper route, and I walked the tenement canyons of Frenchtown delivering The Monument Times, dodging bullies and dogs, wondering what I was doing here on the planet Earth, not knowing yet that the deep emptiness inside me was loneliness.

I felt like a ghost on Mechanic Street, transparent as rain, until the growling of Mr. Mellier's dog restored my flesh and blood and hurried me on my way. I was always glad to arrive home, where my mother, who looked like a movie star, welcomed me with a kiss and a hug. My mother filled the tenement with smells, cakes in the oven, hot donuts in bubbling oil, and hamburg laced with onions sizzling in the black pan she called the Spider. She loved books, lilac cologne, and me.

My mother was vibrant, a wind chime, but my father was a silhouette, as if obscured by a light shining behind him. He was closer to me waving from the street than nearby in the tenement or walking beside me. On summer Saturdays, the men gathered at the Happy Times bar or in Rouleau's Barber Shop and talked about the Boston Red Sox and the prospects of a layoff at the Monument Comb Shop while my brother, Raymond, swapped baseball cards in Pee Alley with his best friend, Alyre Tournier. I stood beside my father as he listened to what the men were saying, smoking his Chesterfields, and I wished I could be like him, mysterious, silent.

I was not famous in the schoolyard, or on the street corners, content to cheer for Raymond, who was a star at everything, baseball at Cartier's Field, Buck Buck How Many Fingers Up? in the schoolyard, while I read The Adventures of Tom Sawyer or A Study in Scarlet on the piazza, avoiding the possibility of dropping a fly ball in center field.

My paper route took me from the green three-decker next to the Boston and Maine railroad tracks where downtown Monument met Frenchtown, along Mechanic and all the numbered streets from First to Twelfth. My last customer was Mr. Lottier at the end of Mechanic Street next to the sewer beds. I held my nose as I tossed the paper to his piazza. He always smiled when he paid me on Friday, as if his nose didn't work.

That summer, Frenchtown was a place of Sahara afternoons, shadows in doorways, lingering evenings, full of unanswered questions and mysteries.

It was also the summer of my twelfth birthday, the summer of Sister Angela and Marielle LeMoyne (even though she was dead) And my brother, Raymond, and all the others, but especially my uncle Med and my father.

And finally it was the summer of the airplane.