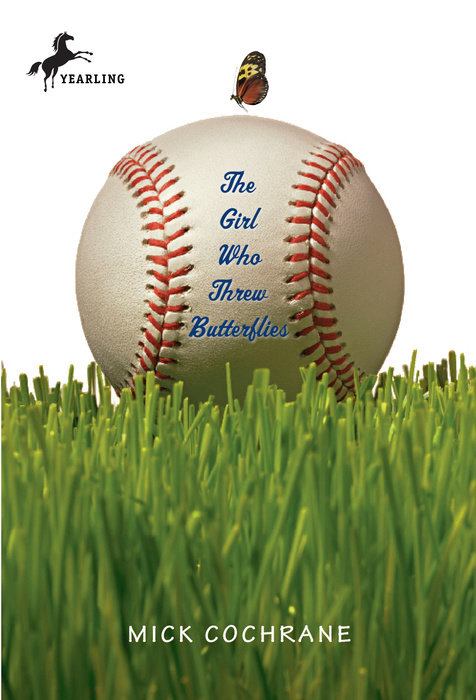

The Girl Who Threw Butterflies

For an eighth grader, Molly Williams has more than her fair share of problems. Her father has just died in a car accident, and her mother has become a withdrawn, quiet version of herself.

Molly doesn’t want to be seen as “Miss Difficulty Overcome”; she wants to make herself known to the kids at school for something other than her father’s death. So she decides to join the baseball team. The boys’ baseball team. Her father taught her how to throw a knuckleball, and Molly hopes it’s enough to impress her coaches as well as her new teammates.

Over the course of one baseball season, Molly must figure out how to redefine her relationships to things she loves, loved, and might love: her mother; her brilliant best friend, Celia; her father; her enigmatic and artistic teammate, Lonnie; and of course, baseball.

Mick Cochrane is a professor of English and the Lowery Writer-in-Residence at Canisius College in Buffalo, New York, where he lives with his wife and two sons.

An Excerpt fromThe Girl Who Threw Butterflies

1. A HEARTBREAKING DREAM ABOUT TOAST

On Monday, after band rehearsal and intramurals, when Molly got home from school, her mother was sitting at the kitchen table going through the day's mail. It was after six, daylight saving time now, and still light, thank god. Even in Buffalo, the snowiest, grayest place on earth, spring eventually came.

Her mother had changed from her work clothes into her white designer sweats, matching pants and top with padded shoulders, which made her look to Molly like a fencer--all she needed was a little red heart.

She had cable news playing low on the countertop portable, a bottle of water and a pile of catalogs in front of her. It was what her mother did after work. Her ritual unwinding. She'd page through the glossy daily stack of catalogs one by one, turning the pages mechanically, looking irritated, angry even, fierce lines on her forehead. It seemed mysterious to Molly. Was her mother mad at Eddie Bauer? At Pottery Barn and Talbots? Dissatisfied with L.L.Bean's selection of boots and raingear, with Williams-Sonoma's pots and pans? It didn't make any sense. Her mother occasionally bought stuff, blouses and sweaters usually, always the same color, teal, which was weird enough--how much teal-colored clothing do you need, really?

As far as Molly could tell, her mother almost always returned whatever she bought. The UPS guy brought packages, and her mother opened them, unpinned and unfolded and held things up, sometimes tried them on. But then she'd usually just reassemble the packages and readdress them. She drove them around in her car for a few days and eventually dropped them off at the post office. To Molly, it seemed like a lot of work. Why subject yourself to such misery? What was the point?

Molly had learned not to interrupt her. Her mother was in some distant, ticked-off, unreachable place--the Planet of Inexplicable Exasperation. Molly put down her backpack and saxophone case, grabbed an apple from the fridge, sat down, and waited. There was nothing that looked like dinner happening anywhere in the kitchen. Why bother cooking for just the two of us? her mother had gotten into the habit of asking. Sometimes, with her dad at work, they used to make dinner together, Molly and her mother. They used to wash and chop vegetables and talk and even joke a little. Molly liked it--it was like their own little cooking show. But no more, not for a long time. That show got canceled. Nowadays they mostly ordered out, subs or Chinese, pizza and wings. Molly missed her dad's cooking. He had only a handful of meals, spaghetti and stir-fry and omelets and meat loaf, that was his rotation, nothing fancy, but always tasty.

On television the square-headed security czar seemed to be changing the threat level while baseball scores crawled across the bottom of the screen. The Cubs had beaten the Pirates, 12-1, which pleased Molly, because it would have pleased her father. They were his team. He'd grown up listening to their games on the radio. The Cubs were lovable losers. They hadn't won the World Series for something like a hundred years. No matter. Her dad had always paid attention to the scores, and now, out of habit, Molly couldn't help but do the same.

"So how was your day?" her mother asked, her eyes still scanning the Sharper Image catalog in front of her--ionizing air cleaners, massage chairs, turbo-groomers.

"Fine," Molly said. Most days this was the right answer. It meant that she had negotiated another day without disaster, steered her little boat through the rocky waters of eighth grade without capsizing. She hadn't failed anything, she hadn't been given detention. In the past ten hours she'd done nothing to ruffle her mother's sense of well-being.

"What about rehearsal?" her mother asked. Sometimes she wanted more. What her English teacher called "supporting detail." She needed to "show" not "tell" her mother about the fineness of her day. Specifics. Molly would offer up something, a success, a little academic triumph she'd been saving--"You know that social studies test I was studying for? I got a ninety-eight!"

This was just what her mother wanted: evidence that Molly was a Good Kid on the Right Path, a girl making Smart Choices, the daughter of a Good Mother. Yes, her father had died six months ago--exactly six months ago; today was the anniversary, the fourth of April. But she was doing fine, she was resilient. Molly understood her part in this story perfectly: She was the brave-hearted poster girl, Miss Difficulty Overcome.

"We're playing a movie medley for the pops concert," Molly said. "Star Wars, The Pink Panther. I might get a solo."

"That's great," her mother said.

"And I lent Ryan Vogel my last reed. I need to get some more.”

"That was nice of you."

What Molly didn't tell her mother was that Ryan, the other tenor player, who had toxic BO and dog breath, who was a volcano of rude eruptions and nasty remarks, had pointed toward her case with his own last, wrecked, saliva-covered reed and grunted something--she'd recognized only "gimme." She'd tossed him her entire pack and hoped he'd leave her alone. There was nothing nice about the transaction; it felt like a holdup, a mugging.

"Very nice of me," Molly said, and smiled a dopey, mock-charming smile. She framed her face with her fingers and tilted her head. "I'm a very nice person."

There was so much she couldn't tell her mother. How, for example, she had dreamed about her father again the night before. It was nothing especially dreamlike, nothing weird or unusual, nothing symbolic. On the contrary, it was beautifully ordinary. Her dad, sitting across from her at the kitchen table, spreading jam on a piece of toast, wearing his favorite plaid shirt, frayed at the collar, his weekend shirt.

In the dream her dad smiled, a little sadly, maybe, as if he knew something she didn't, and handed her a plate with the toast on it, two slices, strawberry jam, cut diagonally, and it looked perfect, the most delicious thing imaginable. She could smell that warm-toast smell, even in her dream, the best, coziest smell in the world. And when she was wrenched out of her dream and back into the world--her mother rapping on her bedroom door as she walked by, "Six-thirty, Molly, time to get up"--it was terrible, like another death, just as cruel.

What would be the point? Maybe her mother had her own dreams. In the past six months, Molly had come to understand that the most important stuff, what was closest to the bone, was just what you never talked about. There were no words for it. A heartbreaking dream about toast. The trivial and silly is what you spend your day chattering about. You could ask your friends how they liked your hair, but you could never ask them what you really wanted to know: Is there hope for me, yes or no?