And so it begins in front of the fire, the story of two twin sisters. One remains with her family in their lovely country house, where yellow roses perfume the air. The other waits for her in another house, where she stands alone at huge arched windows. She is restless, pacing wooden floors that creak in the night when a cat jumps down from the bed to chase at shadows.

“What are their names?” the girl asks. “The sisters.” “Arabella and Henrietta.”

“Are they lonely?” asks the girl.

“They belong together,” says the mother. “And it makes them sad to be apart.”

“Can’t you tell a happy story?” the girl asks.

“With puppies and a garden?”

“Yes!” says the girl.

“I’m only telling it the way my mother told it to me,” the mother says.

“And will there be puppies?” the girl persists. “Or only gloomy girls at windows?”

“Well, their dog, Muffin, wasn’t exactly a puppy, but she was very small. And, there was a beautiful garden. I can picture it perfectly.

And so it begins in front of the fire, the story of two twin sisters. One remains with her family in their lovely country house, where yellow roses perfume the air. The other waits for her in another house, where she stands alone at huge arched windows. She is restless, pacing wooden floors that creak in the night when a cat jumps down from the bed to chase at shadows.

“What are their names?” the girl asks. “The sisters.” “Arabella and Henrietta.”

“Are they lonely?” asks the girl.

“They belong together,” says the mother. “And it makes them sad to be apart.”

“Can’t you tell a happy story?” the girl asks.

“With puppies and a garden?”

“Yes!” says the girl.

“I’m only telling it the way my mother told it to me,” the mother says.

“And will there be puppies?” the girl persists. “Or only gloomy girls at windows?”

“Well, their dog, Muffin, wasn’t exactly a puppy, but she was very small. And, there was a beautiful garden. I can picture it perfectly. But we should start at the beginning.”

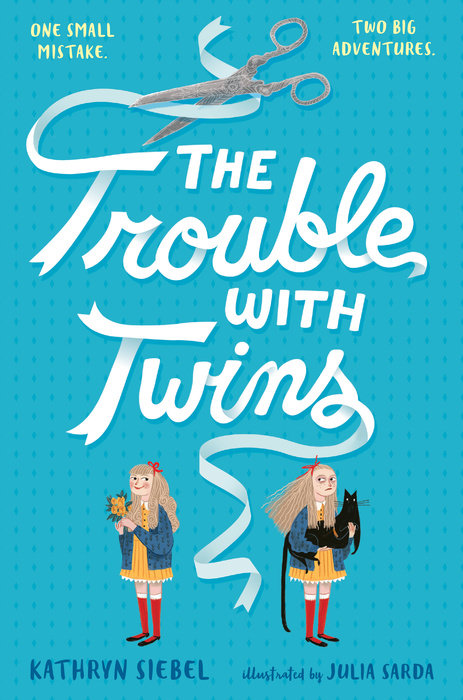

Henrietta and Arabella Osgood were born on the second and third days of April. When they were little, they were everything to each other. They slept in the same crib and wore matching baby outfits. They dreamed the same dreams and played together. People said they learned to talk their own secret language that no one else could understand. They were both beautiful girls, but from the start Arabella was somehow more beautiful than Henrietta. And that is where the trouble began.

Since everyone knew they were twins, nobody could understand why they seemed so different. Arabella was always smiling and laughing, her pink cheeks creased by deep dimples, a charming gap between her two front teeth. Her clothes were spotless, and her glossy blond hair was perfectly combed. Every day their nanny, Rose, arranged it in a new and elaborate hairstyle, tying off the ends with bits of colorful ribbon that blew gently in the breeze.

Henrietta, on the other hand, was as quiet and serious as an elderly professor. She seldom spoke, rarely smiled. Crumbs tumbled down the front of her clothes. And her hair! Well, Rose always meant to get to it, but she had such fun fixing Arabella’s that she never did.

Their differences had never mattered to the two of them, but they had always influenced how others treated them. When they were babies, Rose always fed Arabella first and held her more. When they grew older, Arabella was the one the girls’ parents asked to perform for guests. Arabella would recite a poem or sing a song for the grown-ups before they went off to dinner. The adults would smile at her and clap their hands in delight, and they barely noticed Henrietta as they passed her on the way to the dining room. And even when nobody else was around, Mr. and Mrs. Osgood were always praising Arabella. “Have you ever seen such blue eyes?” they would ask each other, gazing fondly at Arabella. “Doesn’t she have the most delicate fingers? Born to play the harp.” Of course they were never mean to Henrietta. At least not at first. But it was clear to everyone who ever met them that the Os-goods liked Arabella best. Watching them fawn over Arabella, Henrietta stood back, saying nothing and feeling too much.

At school the girls sat near each other: Arabella at a clean, perfect desk from which she unfailingly gave the right answer, and Henrietta at an older one with gum under the seat. Inside were forgotten peanut butter and jelly sandwiches that Henrietta hadn’t wanted to eat and smudgy homework papers that showed, as her teacher Mr. Stilton-Sterne was always saying, that Henrietta couldn’t be paying very much attention.

Outside the house, Arabella was always busy with friends. The other girls invited Arabella to their birthday parties, where they ate tiny, delicious chocolate candies from pink paper cups under birthday streamers and balloons. On the playground, they hopscotched together and gathered in tight circles, giggling, whispering, and pulling up their socks. Arabella didn’t mean to leave Henrietta out of all the fun; she just seemed to lose track of her sister, and Henrietta had to either find someone else to skip rope with or make peace with standing off in a corner all alone.

But at home they built their own world. They lined up dolls and stuffed bears, poured them invisible tea, and invented their conversation. When the sun shone, they dressed each other in their mother’s old dresses; they added paper crowns and wings and ran through the garden, playing fairy princess. When it rained, their heads were bent over drawing paper as they passed crayons to and fro in companionable silence. They were mirror images, touchstones. The sight of the other steadied each of them. They ate the same meals, listened to the same conversations between their parents at dinner, received the same gifts in different colors. Both sisters knew with a look what the other was thinking, and words were seldom necessary. They ended each day whispering good night across the short space between their matching beds.

Yet as soon as they arrived at school every morning, things changed. There was so much more going on there, and Arabella was always at the center of it all, encircled by her adoring friends. Henrietta, on the other hand, spent her days by the wrought-iron fence on the edges of the playground, staring at Arabella and her friends.

“Mother,” asks the girl by the fire, “if Arabella and Henrietta are twins, how could they be born on different days?”

“It does happen sometimes,” the mother insists. “Henrietta was born just before midnight at the end of April second. And Arabella was born a bit after, in the wee hours of April third.”

“Well, that’s very unusual, don’t you think?”

“They were very unusual sisters.”

“And that bit about dreaming the same dreams. How could anyone know that?” the girl asks.

“I know these two girls quite well,” the mother says.

“Do you want to hear their story or not?”