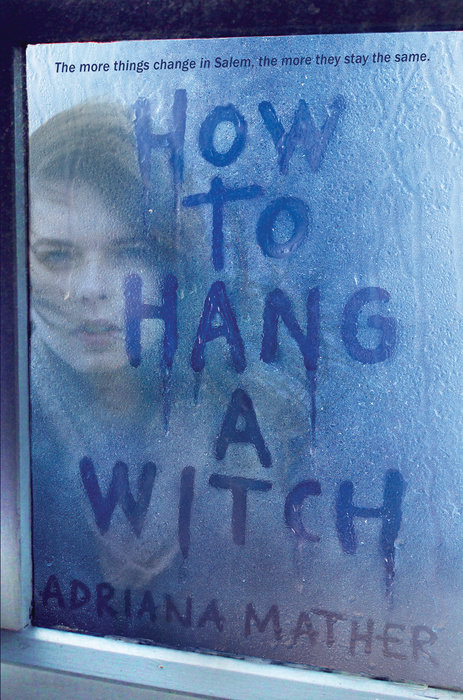

How to Hang a Witch

Author Adriana Mather

The #1 New York Times bestseller!

It’s the Salem Witch Trials meets Mean Girls in this New York Times bestselling novel from one of the descendants of Cotton Mather, where the trials of high school start to feel like a modern-day witch hunt for a teen with all the wrong connections to Salem’s past.

Salem, Massachusetts, is the site of the infamous witch trials and the new home of Samantha Mather. Recently transplanted from New York City, Sam…

The #1 New York Times bestseller!

It’s the Salem Witch Trials meets Mean Girls in this New York Times bestselling novel from one of the descendants of Cotton Mather, where the trials of high school start to feel like a modern-day witch hunt for a teen with all the wrong connections to Salem’s past.

Salem, Massachusetts, is the site of the infamous witch trials and the new home of Samantha Mather. Recently transplanted from New York City, Sam and her stepmother are not exactly welcomed with open arms. Sam is the descendant of Cotton Mather, one of the men responsible for those trials—and almost immediately, she becomes the enemy of a group of girls who call themselves the Descendants. And guess who their ancestors were?

If dealing with that weren’t enough, Sam also comes face to face with a real, live (well, technically dead) ghost. A handsome, angry ghost who wants Sam to stop touching his stuff. But soon Sam discovers she is at the center of a centuries-old curse affecting anyone with ties to the trials. Sam must come to terms with the ghost and find a way to work with the Descendants to stop a deadly cycle that has been going on since the first accused witch was hanged. If any town should have learned its lesson, it’s Salem. But history may be about to repeat itself.

“It’s like Mean Girls meets history class in the best possible way.” —Seventeen Magazine

“Mather shines a light on the lessons the Salem Witch Trials can teach us about modern-day bullying—and what we can do about it.” —Bustle

“Strikes a careful balance of creepy, fun, and thoughtful.” —NPR

I am utterly addicted to Mather’s electric debut. It keeps you on the edge of your seat, twisting and turning with ghosts, witches, an ancient curse, and—sigh—romance. It’s beautiful. Haunting. The characters are vivid and real. I. Could. Not. Put. It. Down.” —Jennifer Niven, bestselling author of All the Bright Places

An Excerpt fromHow to Hang a Witch

Chapter One

Too Confident

Like most fast-talking, opinionated New Yorkers, I have an affinity for sarcasm. At fifteen, though, it’s hard to convince anyone that sarcasm’s a cultural thing and not a bad attitude. Especially when your stepmother can’t drive, ’cause she’s also from New York, and spills your coffee with maniacal brake pounding.

I wipe a dribble of hazelnut latte off my chin. “It’s okay. Don’t worry about it. I love wearing my coffee.”

Vivian keeps her hand poised over the horn, like a cat waiting to pounce. “All your clothes have holes in them. Coffee isn’t your problem.”

If it’s possible for someone to never have an awkward moment, socially or otherwise, then that someone is my stepmother. When I was little, I admired her ability to charm roomfuls of people. Maybe I thought it would rub off on me—an idea I’ve since given up on. She’s perfectly put together in a way I’ll never be, and my vegan leather jacket and torn black jeans drive her crazy. So now I just take joy in wearing them to…

Chapter One

Too Confident

Like most fast-talking, opinionated New Yorkers, I have an affinity for sarcasm. At fifteen, though, it’s hard to convince anyone that sarcasm’s a cultural thing and not a bad attitude. Especially when your stepmother can’t drive, ’cause she’s also from New York, and spills your coffee with maniacal brake pounding.

I wipe a dribble of hazelnut latte off my chin. “It’s okay. Don’t worry about it. I love wearing my coffee.”

Vivian keeps her hand poised over the horn, like a cat waiting to pounce. “All your clothes have holes in them. Coffee isn’t your problem.”

If it’s possible for someone to never have an awkward moment, socially or otherwise, then that someone is my stepmother. When I was little, I admired her ability to charm roomfuls of people. Maybe I thought it would rub off on me—an idea I’ve since given up on. She’s perfectly put together in a way I’ll never be, and my vegan leather jacket and torn black jeans drive her crazy. So now I just take joy in wearing them to her dinner parties. Gotta have something, right?

“My problem is, I don’t know when I’ll see my dad,” I say, staring out at the well-worn New England homes, with their widow’s walks and dark shutters.

Vivian’s lips tighten. “We’ve been through this a hundred times. They’ll transfer him to Mass General sometime this week.”

“Which is still an hour from Salem.” This is the sentence I’ve repeated since I found out three weeks ago that we had to sell our New York apartment, the apartment I’ve spent my entire life in.

“Would you rather live in New York and not be able to pay your father’s medical bills? We have no idea how long he’ll be in a coma.”

Three months, twenty-one days, and ten hours. That’s how long it’s already been. We pass a row of witch-themed shops with dried herbs and brooms filling their windows.

“They really love their witches here,” I say, ignoring Vivian’s last question.

“This is one of the most important historical towns in America. Your relatives played a major role in that history.”

“My relatives hanged witches in the sixteen hundreds. Not exactly something to be proud of.”

But in truth, I’m super curious about this place, with its cobblestone alleys and eerie black houses. We pass a police car with a witch logo on the side. As a kid, I tried every tactic to get my dad to take me here, but he wouldn’t hear of it. He’d say that nothing good ever happens in Salem and the conversation would end. There’s no pushing my dad.

A bus with a ghost-tour ad pulls in front of us. Vivian jerks to a stop and then tailgates. She nods at the ad. “There’s a nice provincial job for you.”

I crack a smile. “I don’t believe in ghosts.” We make a right onto Blackbird Lane, the street on the return address of the cards my grandmother sent me as a child.

“Well, you’re the only one in Salem who feels that way.” I don’t doubt she’s right.

For the first time during this roller coaster of a car ride, my stomach drops in a good way. Number 1131 Blackbird Lane, the house my dad grew up in, the house he met my mother in. It’s a massive two-story white building with black shutters and columned doorways. The many peaks of the roof are covered with dark wooden shingles, weathered from the salty air. A wrought-iron fence with pointed spires surrounds the perfectly manicured lawn.

“Just the right size,” Vivian says, eyeing our new home.

The redbrick driveway is uneven with age and pushed up by tree roots. Vivian’s silver sports car jostles as we make our way through the black arched gate and roll to a stop.

“Ten people could live here and never see each other,” I reply.

“Like I said, just the right size.”

I pull my hair into a messy ball on top of my head and grab the heavy duffel bag at my feet. Vivian’s already out of the car, and her heels click against the brick. She makes her way toward a side door with an elaborate overhang.

I take a deep breath and open my car door. Before I get a good look at our new home, a neighbor comes out of her blue-on-blue house and waves enthusiastically.

“Helllloooo! Well, hello there!” she says with a smile bigger than I’ve ever seen on a stranger as she crosses a patch of lawn to get to our driveway.

She has rosy cheeks and a frilly white apron. She could have stepped out of a housekeeping magazine from the 1950s.

“Samantha,” she says, and beams. She holds my chin to inspect my face. “Charlie’s daughter.”

I’ve never heard anyone call my dad by a nickname. “Uh, Sam. Everyone calls me Sam.”

“Nonsense. That’s a boy’s name. Now, aren’t you pretty. Too skinny, though.” She steps back to get a proper look. “We’ll fix that in no time.” She laughs a full, tinkling laugh.

I smile, even though I’m not sure she’s complimenting me. There’s something infectious about her happiness. She examines me, and I cross my arms self-consciously. My duffel bag falls off my shoulder, jerking me forward. I trip.

“Jaxon!” she bellows toward her blue house without saying a word about my clumsiness. A blond guy who looks seventeenish exits the side door just as I get hold of the duffel strap. “Come take Samantha’s bag.”

As he gets closer, his sandy hair flops into his eyes. Blue. One corner of his mouth tilts in a half smile. I stare at him. Am I blushing? Ugh, so embarrassing. He reaches for the bag, now awkwardly hanging from my elbow.

I reposition it onto my shoulder. “No, it’s fine.”

“This is my son, Jaxon. Isn’t he adorable?” She pats him on the cheek.

“Mom, really?” Jaxon protests.

I smile at them. “So, you know my dad?”

“Certainly. And I knew your grandmother. Took care of her and the house when she got older. I know this place inside and out.” She puts her hands on her hips.

Vivian approaches, frowning. “Mrs. Meriwether? We spoke on the phone.” She pauses. “You have the keys, I assume?”

“Sure do.” Mrs. Meriwether reaches into her apron pocket and retrieves a set of skeleton keys rubbed smooth in places from years of use. She glances at her watch. “I’ve got chocolate croissants coming out of the oven any minute now. Jaxon will give you a tour of—”

“No, that’s alright. We can show ourselves around.” There’s a finality in Vivian’s response. Vivian doesn’t trust overly friendly people. We had a doorman once who used to bring me treats, and she got him fired.

“Actually,” I say, “do you know which room used to be my dad’s?”

Mrs. Meriwether lights up. “It’s all ready for you. Up the stairs, take a left, all the way down the hall. Jaxon will show you.”

Vivian turns around without a goodbye. Jaxon and I follow her to the door.

Jaxon watches me curiously as we go inside. “I’ve never seen you here before.”

“I’ve never been here before.”

“Even when your grandmother was alive?” He closes the door behind us with a click.

“I never met my grandmother.” It’s weird to admit that.

In the front foyer are piles of boxes—all of our personal belongings from the City. Vivian sold everything heavy when she found out this place was furnished.

We step past the boxes into an open space with glossy wooden floors, a wrought-iron chandelier, and a giant staircase. Vivian’s heels click somewhere down the hallway to the left—a sound that follows her around like a shadow. As a child, I could always find her by listening for it, even in a roomful of women in high heels. I wouldn’t be surprised if she slept in those shoes.

I take in our home for the first time. Paintings in gold frames hang on the walls, separated by sconces with bulbs shaped like candles. Everything’s antique and made of dark wood, the opposite of our modern apartment in NYC. This is some fairy-tale storybook business, I think, looking at the curved staircase with its smooth wooden banisters and Oriental rug running up the middle.

“This way.” Jaxon nods toward the staircase. He lifts my bag off my shoulder and starts up the stairs.

“I could’ve carried that myself.”

“I know. But I wouldn’t want you to fall again. Stairs do more damage than driveways.” So he definitely saw me trip. He smiles at my expression.

This guy is too confident for his own good. I follow him, holding the banister in case my clumsiness makes a second appearance.

Jaxon turns left at the top of the stairs. We pass a bedroom with a burgundy comforter and a canopy that any little girl would go bonkers over. After the bedroom, there’s a bathroom with a giant claw-foot tub and a mirror with a gold-plated frame.

He stops at the end of the hall in front of a small door that looks like it could use a fresh coat of paint. The doorknob’s shaped like a flower with shiny brass petals. A daisy, maybe? I twist it, and the wood groans as the door swings open.

I gasp.