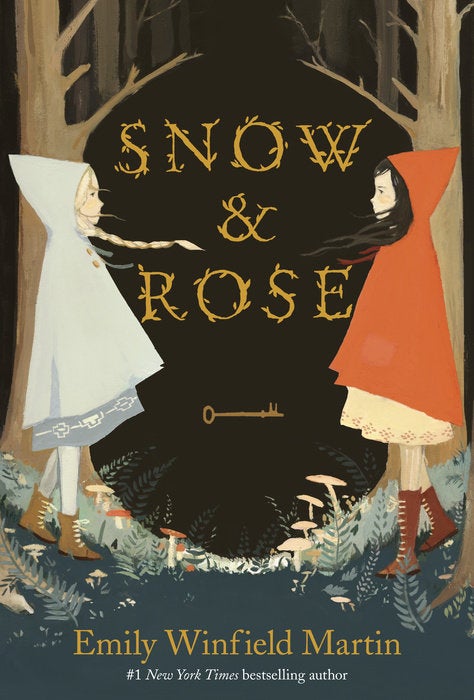

Snow and Rose

An Excerpt fromSnow and Rose

Once, there were two sisters.

Rose had hair like threads of black silk and cheeks like two red petals and a voice that was gentle and sometimes hard to hear. Snow had hair like white swan down and eyes the color of the winter sky, with a laugh that was sudden and wild.

They lived in a cottage in the woods, but it hadn’t always been so. “Tell me a story,” Snow called in the dark. She moved restlessly, wide awake in her bed.

“You’ll wake Mama,” Rose murmured. “Go back to sleep.”

Snow sat up, her bed creaking. “Rose?” Her whisper drifted in the dark. “Please?”

Their bedroom was a loft that lay above the hearth and kitchen and below a pointed ceiling. On one side were the sisters’ beds. On the other side was their mother’s bed. Rose peered through the gap in the faded screen that turned one small room into two very tiny ones. The blue light in the window showed the curve of their mother’s side rising and falling softly.

Rose sighed. “Okay, but I’ll come over there.” The hush of a match sounded as Rose lit the yellow beeswax stump between their beds, followed by a few soft tiptoed thumps as her feet padded across the floor. She climbed under the covers of Snow’s bed.

“Your feet are freezing,” Snow whispered.

Rose drew her knees up to her chest. “Which story do you want to hear?” Rose asked. Her dark hair glowed with glints of red and gold in the candle’s light. “The one about the magic lamp?”

“No,” Snow said, pulling the covers tightly around her shoulders. She smiled, her pale hair a messy tumble on the pillow.

“The mermaid and the monkey?” Rose asked.

“No,” Snow whispered impatiently. “Not that one.”

“Or the fairy tale about—”

“No, no fairy tales.” Snow tugged gently on the sleeve of Rose’s nightgown. “Tell the story of us.”

After another sigh, Rose began.

“Once upon a time,” Rose whispered in her best storyteller’s voice, “there were two girls, one with black hair and one with white. They were born to a nobleman who was as tall and as broad as he was gentle and kind. Their mother was from a common family, but she had a rare and delicate beauty, like—”

“Like a Siamese cat,” Snow offered.

“Yes, like a Siamese cat,” Rose continued softly. “And their mother was a painter and sculptor, who loved to wake up the things she said were asleep inside big slabs of marble, and her statues filled the sculpture garden. And their father loved to build places that didn’t exist until he imagined them. He loved to read about all the things that other people had imagined and built, so he had a library with shelves that reached to the ceiling.

“Their mother and father loved each other, too, of course, more than books or sculptures. But more than anything else, they loved their two daughters.

“And since love is something you cannot see, the mother and father tried their best to make an invisible thing visible. So when the girls were both still very small, their parents commissioned a spectacular garden, a wonder that people would come from miles and miles to see. Stretching the entire length of the house, this garden was like no garden that had ever existed or will ever exist again.

“Half of the garden was filled entirely with white flowers of every kind—with pale, delicate bells of lily of the valley, spires of vanilla foxgloves with speckled throats, climbing moonflower vines, and bright-eyed anemones, from the tiniest white daisy to ivory dahlias the size of dinner plates. And—”

“And it was called the Snow Garden,” Snow interrupted.

“And it was called the Snow Garden,” repeated Rose with a sad smile. “And the other half bloomed only in red: vermilion poppies and scarlet pansies and wine-colored snapdragons and Japanese lanterns the color of fire. And dozens and dozens of roses, each with a hundred red petals . . .”

Rose trailed off. She knew hearing the story made Snow happy; otherwise she wouldn’t ask for it all the time. But for Rose, in the telling of it, she was left with a hollow that grew with each word.

Rose knew her sister was the kind of person who wanted to see or hear or taste something she loved over and over again, to remind herself that it was real. Rose was another kind of person: she wanted to hold on to a thing she loved as tightly as she could. She wanted to keep it special and safe, for fear that it might get used up—or worse, that it might escape, like sand or sugar slipping between her fingers.

“You know a lot of words for red,” Snow whispered. Her eyes were closed. “Now tell about the swans.”

Rose looked at her sister’s face, a content pale moon in the dark.

Rose breathed in and pulled the quilt to her chest. She continued the story dutifully, her voice as low as she could make it, so low it was barely there. “And in the center of the Snow Garden and the Rose Garden was a pond ringed with willows, and tracing circles on the water were two swans, one white with a dark golden beak, and the other coal black with a beak of the brightest red.

“And this is where the girls were born, the place they grew up. This is where they had closets stuffed with dozens of beautiful dresses, where their porcelain dolls had so many lovely things to wear they needed closets of their own. This is where they had an extremely fat cat named Earl Grey, and where they had their lessons and acted out plays and had their tea. And when they played hide-and-seek, Snow would always hide in the sculpture garden and Rose would always hide in the library, so it wasn’t even that good a game. . . .”

Rose looked down to see if Snow was awake. Her sister’s eyelids fluttered, but she didn’t seem to notice that the story had stopped.

Rose went on, her voice even softer than before, as quiet as a breath. “And at night, this is where they were tucked into big brass beds wrought with flowers and birds, and where their father would read them to sleep or tell them stories about magic lamps and dragons and faraway places. . . .”

Gently, Rose climbed out of the warm covers and tucked them around Snow’s shoulders. “As their mother put out the lights, their father would say, ‘Go to sleep, my only Snow. Go to sleep, my only Rose.’”

She made her way back to her own bed and snuffed out the candle.

“The end.”

Rose had hair like threads of black silk and cheeks like two red petals and a voice that was gentle and sometimes hard to hear. Snow had hair like white swan down and eyes the color of the winter sky, with a laugh that was sudden and wild.

They lived in a cottage in the woods, but it hadn’t always been so. “Tell me a story,” Snow called in the dark. She moved restlessly, wide awake in her bed.

“You’ll wake Mama,” Rose murmured. “Go back to sleep.”

Snow sat up, her bed creaking. “Rose?” Her whisper drifted in the dark. “Please?”

Their bedroom was a loft that lay above the hearth and kitchen and below a pointed ceiling. On one side were the sisters’ beds. On the other side was their mother’s bed. Rose peered through the gap in the faded screen that turned one small room into two very tiny ones. The blue light in the window showed the curve of their mother’s side rising and falling softly.

Rose sighed. “Okay, but I’ll come over there.” The hush of a match sounded as Rose lit the yellow beeswax stump between their beds, followed by a few soft tiptoed thumps as her feet padded across the floor. She climbed under the covers of Snow’s bed.

“Your feet are freezing,” Snow whispered.

Rose drew her knees up to her chest. “Which story do you want to hear?” Rose asked. Her dark hair glowed with glints of red and gold in the candle’s light. “The one about the magic lamp?”

“No,” Snow said, pulling the covers tightly around her shoulders. She smiled, her pale hair a messy tumble on the pillow.

“The mermaid and the monkey?” Rose asked.

“No,” Snow whispered impatiently. “Not that one.”

“Or the fairy tale about—”

“No, no fairy tales.” Snow tugged gently on the sleeve of Rose’s nightgown. “Tell the story of us.”

After another sigh, Rose began.

“Once upon a time,” Rose whispered in her best storyteller’s voice, “there were two girls, one with black hair and one with white. They were born to a nobleman who was as tall and as broad as he was gentle and kind. Their mother was from a common family, but she had a rare and delicate beauty, like—”

“Like a Siamese cat,” Snow offered.

“Yes, like a Siamese cat,” Rose continued softly. “And their mother was a painter and sculptor, who loved to wake up the things she said were asleep inside big slabs of marble, and her statues filled the sculpture garden. And their father loved to build places that didn’t exist until he imagined them. He loved to read about all the things that other people had imagined and built, so he had a library with shelves that reached to the ceiling.

“Their mother and father loved each other, too, of course, more than books or sculptures. But more than anything else, they loved their two daughters.

“And since love is something you cannot see, the mother and father tried their best to make an invisible thing visible. So when the girls were both still very small, their parents commissioned a spectacular garden, a wonder that people would come from miles and miles to see. Stretching the entire length of the house, this garden was like no garden that had ever existed or will ever exist again.

“Half of the garden was filled entirely with white flowers of every kind—with pale, delicate bells of lily of the valley, spires of vanilla foxgloves with speckled throats, climbing moonflower vines, and bright-eyed anemones, from the tiniest white daisy to ivory dahlias the size of dinner plates. And—”

“And it was called the Snow Garden,” Snow interrupted.

“And it was called the Snow Garden,” repeated Rose with a sad smile. “And the other half bloomed only in red: vermilion poppies and scarlet pansies and wine-colored snapdragons and Japanese lanterns the color of fire. And dozens and dozens of roses, each with a hundred red petals . . .”

Rose trailed off. She knew hearing the story made Snow happy; otherwise she wouldn’t ask for it all the time. But for Rose, in the telling of it, she was left with a hollow that grew with each word.

Rose knew her sister was the kind of person who wanted to see or hear or taste something she loved over and over again, to remind herself that it was real. Rose was another kind of person: she wanted to hold on to a thing she loved as tightly as she could. She wanted to keep it special and safe, for fear that it might get used up—or worse, that it might escape, like sand or sugar slipping between her fingers.

“You know a lot of words for red,” Snow whispered. Her eyes were closed. “Now tell about the swans.”

Rose looked at her sister’s face, a content pale moon in the dark.

Rose breathed in and pulled the quilt to her chest. She continued the story dutifully, her voice as low as she could make it, so low it was barely there. “And in the center of the Snow Garden and the Rose Garden was a pond ringed with willows, and tracing circles on the water were two swans, one white with a dark golden beak, and the other coal black with a beak of the brightest red.

“And this is where the girls were born, the place they grew up. This is where they had closets stuffed with dozens of beautiful dresses, where their porcelain dolls had so many lovely things to wear they needed closets of their own. This is where they had an extremely fat cat named Earl Grey, and where they had their lessons and acted out plays and had their tea. And when they played hide-and-seek, Snow would always hide in the sculpture garden and Rose would always hide in the library, so it wasn’t even that good a game. . . .”

Rose looked down to see if Snow was awake. Her sister’s eyelids fluttered, but she didn’t seem to notice that the story had stopped.

Rose went on, her voice even softer than before, as quiet as a breath. “And at night, this is where they were tucked into big brass beds wrought with flowers and birds, and where their father would read them to sleep or tell them stories about magic lamps and dragons and faraway places. . . .”

Gently, Rose climbed out of the warm covers and tucked them around Snow’s shoulders. “As their mother put out the lights, their father would say, ‘Go to sleep, my only Snow. Go to sleep, my only Rose.’”

She made her way back to her own bed and snuffed out the candle.

“The end.”