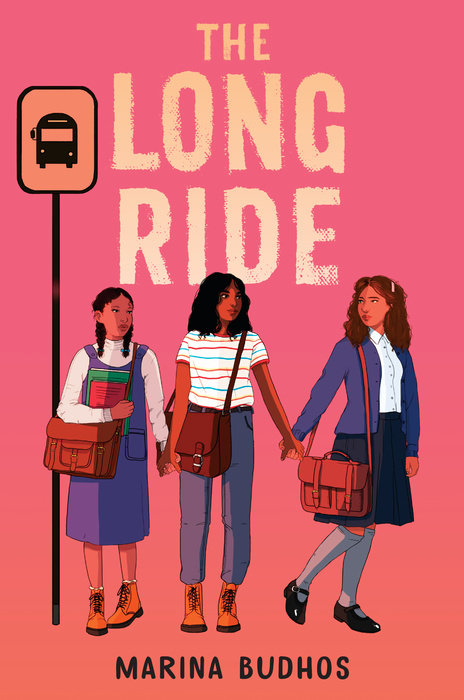

The Long Ride

In the tumult of 1970s New York City, kids are expected to figure out issues of race that adults haven't when seventh graders are bused from their neighborhood in Queens to integrate a new school in South Jamaica.

Jamila, Josie, and Francesca are three mixed-race girls who have always felt like outsiders in their mostly white neighborhood in Queens, but at least they have each other. Now it's seventh grade, and they're part of an experiment where kids will go on a long bus ride to integrate a new school in a black neighborhood. Maybe there the three girls can finally fit in.

But Francesca's parents put her in private school. And Jamila and Josie discover that they're not even in the same classes.

How do they find their place in a school divided between black and white? And what about the boys wanting to be friends--and maybe more? Can kids come together when grown-ups stay apart?

In this tender story of friendship and family love, award-winning author Marina Budhos captures what it's like to tip from twelve to thirteen and to try to carry the dreams of adults.

An Excerpt fromThe Long Ride

Twelve is the best and twelve is the worst.

It’s the breathless swoop at the top of the Ferris wheel, dangling and wishing you could stay. It’s the moment when the wheel’s about to drop, and you’re scared, but it’s thrilling too.

Because twelve is when you clutch for everything to stay the same. But it’s also when you’re tipped forward, ready for something new.

In the spring of sixth grade, our last year in elementary school, Francesca and Josie and me like to lean against the schoolyard fence and stare at the kids in front of the junior high across the street. Girls with long straight hair that swings at their butts. That’s going to be us! But how will I ever get from here to there? I still play with Josie’s dollhouse. I’m afraid of the dark. I sort of giggle about boys, but really I wish they’d leave us alone. When I think about thirteen and having a chest that shows beneath my shirt, my stomach hurts. I wish I could stay right here, fingers on the diamonds of twisted metal, looking out.

Almost-twelve is when I learn about our new school. When everything changes in Queens, and in New York City.

One day I come home with a mimeographed flyer.

“What’s this?” My mother starts reading. Her light brown hair is drawn back into a ponytail. Daddy always says that Mom still looks like the twenty-year-old he met studying at a coffee shop near Columbia University.

“It’s called a pairing.”

“What’s that mean?”

“The seventh graders will go to another school, a new one, in South Jamaica.”

“Why on earth? Our junior high is just a few blocks away!”

“Integration.”

Mom looks at Daddy standing in the door. He nods. Integration.

Integration. That’s a good thing. One of those banner words that snaps brightly over our heads. Last year we did a dance about Martin Luther King Jr. in the gymnasium, all the girls in maroon Danskins. We listened to the “I Have a Dream” speech crackling on speakers. My four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin . . .

Integration is what our family does in quiet and private ways. Mom grew up on Long Island, the daughter of a policeman; she met Daddy when she was studying social work, and he was an engineering student living in Harlem. When her brother, Joe, heard she was dating a man from Barbados, he showed up at her apartment, tapping a crowbar against his palm. Daddy gently invited him to eat keema that he’d cooked for Mom. Uncle Joe laughs now, says that he had to like a guy who cooked for his sister. Still, no one in the family came when they got married at city hall.

Two nights after getting the flyer, Daddy and Mom go to the school meeting, Mom with her cardigan draped over her shoulders and a pleated skirt. Daddy in his usual suit and tie. My parents always get dressed up. One of Mom’s many rules for me and my brother, Karim: “You have to give a certain kind of impression because they’re not used to families like us.” Meaning a tall black man with a hint of East Indian in his face, and his pale, thin wife.

I’m finishing my homework when they come back, arguing softly in the living room about the new plan.

“It’s not that bad,” my mother says.

“Penny, I didn’t work so hard and get myself out of a village school for my daughter to go to school in a poor neighborhood. That’s going backward.”

“It’s all new teachers,” Mom says. “A new building.”

“But why now?”

“Our schools are as segregated as ever.”

He sighs. “I know. But have you ever driven by those streets? The boarded-up windows?” He shakes his head. “My child is not an experiment.”

“If those words came out of our neighbors, you’d be upset.”

“There’s a difference.”

“Is there?”

He doesn’t answer.

*

Me and Josie and Francesca, our families, we’re a link of firsts. No one ever says that exactly. Francesca’s mom, Mrs. George, who has strawberry-blond hair and high cheekbones, and was once a model, often boasts how her husband was the first “someone of his background, growing up on the wrong side of Philadelphia, to sell fine antiques.” He even opened his own shop on the Upper East Side in Manhattan with “the very best quality.” And Daddy was the first one in his family to move off his island to become a geologist and engineer.

Josie’s dad, Mr. Rivera, who wears the same cotton shirts with the big embroidered pockets that my dad likes, has the best “first” story. Mr. Rivera is light-skinned—“café con leche, with lots of the leche,” he teases—while Mrs. Rivera, who grew up on the island of Jamaica, is ebony dark. When the Riveras first came to the rental office here in Cedar Gardens, they were told there were no apartments, and to check back. Every other Monday at nine a.m. Mr. Rivera would call. After a whole year of calling he just showed up at the office. That very day, an old couple who was retiring to Florida had come to hand in their keys. “Why, thank you,” Mr. Rivera said, holding his palm open. The Riveras were the first nonwhite family to live in Cedar Gardens.

We moved in a few years later. Francesca’s family came next and bought the Tudor across the street from our garden apartments. Mr. George said he always dreamed of owning a house like that, and Mrs. George said it reminded her of England. Francesca told me that six months after they moved in, two For Sale signs went up on the block. The first time my mother and father showed up for a block party with a casserole, Daddy said, “You shoulda seen their mouths drop open!” He wasn’t laughing the time we had the N-word scrawled on our milk box, the bottles broken. Or the time a group of boys chased my brother, Karim, home with stones. He still has a tiny pale scar over his right eye.

Our mothers met in the playground, pushing us on swings, watching our older brothers. “If I have a son,” Mrs. George said to Mrs. Rivera, “I hope he looks like yours.”

Our parents always tell us: Don’t wander too far. Stay close, where we can find you. They never say why exactly. But we know. The hot stares from stoops. The neighbor who called the police on Mr. George when they saw him unlocking his own door. Josie’s brother, Manuel, getting chased home from school with boys calling, “Run fast, chocolate bunny!” The worst was when another family like us moved in and someone slipped a lit rag in their basement window. Our dads went over to talk; my mom and Mrs. Rivera made casseroles for the neighbors. But that family didn’t stay long.

Once, I was with my mother buying groceries, when the cashier said, “She’s your daughter? I thought maybe she was your maid’s girl!”

“Are you blind?” I blurted. “We have the same face!”

I know I shouldn’t shoot my mouth off. But it stung. After, my mother told me, “Jamila, don’t ever let something like that get to you. She’s a girl who will never go to college.”

That’s my parents’ answer for everything: grades and school. That will shield you from the hurts from people who aren’t ready for us.