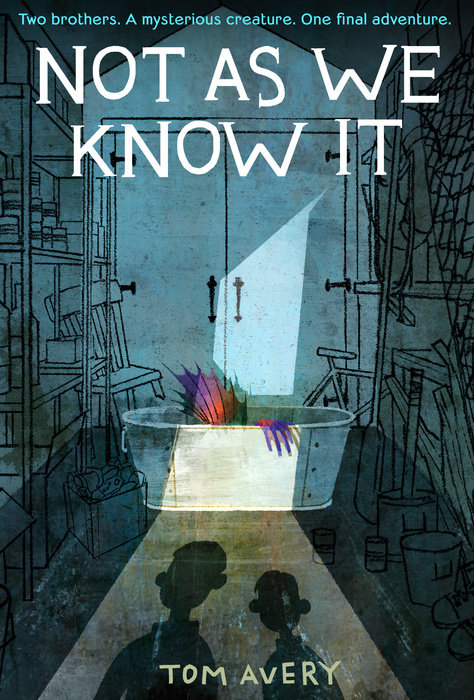

Not As We Know It

For fans of David Almond’s Skellig and Patrick Ness’s A Monster Calls, here is a lyrical, atmospheric, and deeply emotional middle-grade novel with a touch of magical realism.

Twins Jamie and Ned do everything together, from watching their favorite show, Star Trek, to riding their bikes, to beachcombing after a storm. But Ned is sick with cystic fibrosis, and he may someday leave Jamie behind. One day the boys find a strange animal on the beach: smooth flesh on one end, scales at the other, and short arms and legs with long webbed fingers and toes. Could it be a merman, like in the old stories Granddad tells?

Together, the boys name the creature Leonard and decide to hide him in a tub in their garage. But . . . why is Leonard here? Jamie hopes he might bring some miracle that will stop his brother from going where he can no longer follow. But Ned, who grows closer to Leonard every day, doesn’t seem to be getting any better. . . .

"An elegant story of courage and loss." —The Wall Street Journal

"A heartrending but ultimately uplifting adventure novel." —School Library Journal, Starred

"A hauntingly beautiful story about brotherly bonds, wrenching grief, and the untethered hope that everything will somehow work out." —Publishers Weekly, Starred

"Captivating." —Shelf Awareness, Starred

An Excerpt fromNot As We Know It

Treasure

A storm came to Portland. In the night it threw itself against our windows. The thunder called to us. Black clouds gathered across the island. The days were dark.

When storms are finished, Chesil Beach—the stony bank that connects our tiny island in the English Channel to the mainland—is always littered. Driftwood, tangled balls of fishermen’s nets, glass bottles and plastic packets, all lie like God’s rubbish, spilt from a heavenly bin bag.

There’s treasure too. Ned and I go searching amongst the junk. We claim the choicest gems, make them our prize and take them home to our trove.

Dad’s low garage has never been big enough for his van. It’s a low brick building that doesn’t hold a car either. Instead, it’s bursting with the salvage of a dozen storms.

We have collected shoes in all sizes—from a baby’s leather bootie to a yellow rubber wader. There’s a box of bones that sits on a high shelf, topped with a cow’s skull. In an old paint tin stands a rusted and broken knife as long as my forearm. Three forks rattle in the tin when we fetch it down; we are always on the lookout for spoons.

Hats and a leather bag with a golden clasp. A little whale carved from bone. Unopened cans of food, all label-less. A hairbrush. Children’s toys, and books swollen and cracked by the sea’s waves and the sun’s rays. All kinds of fishermen’s tackle hangs about a life-ring that probably saved no one’s life.

Some things took both of us to drag back along the beach: a bicycle frame; a chair with a missing leg; a long, thick oar; a metal tub, like a small bath, that sat in the very middle of the garage.

Once we found the rotted carcass of a seal. Ned said we should take it home as part of our “mission to seek out new life.” The light was failing by the time we got it off the beach and up, up the coast path to our stone cottage and brick garage. Mum made us bury it.

As ever, with this latest storm, we’d waited, watched the lightning, whooped at the crack of thunder. The storm passed and Dad left early for work. One fence panel was down. Mum said to fix it before I thought about doing anything else. I pushed it into place and nailed it to the post. I could hear Ned, inside on the sofa, coughing his lungs up as Mum beat on his chest. I hammered harder and hummed the Star Trek theme tune.

Tony, one of our neighbors, Dad’s mate, beeped his horn as he drove past. I waved. He winked and nodded, his policeman’s helmet bobbing up and down.

From next door, Mrs. Clarke called over the fence, “Will you keep it down!”

“Sorry. I’m nearly finished.”

She huffed, closed the door and returned to her kitchen, glaring from the window.

I hammered the last nail in place as Ned, his treatment over, flew through the front door. Free! We mounted our bikes and coasted down the long hill before leaving them where the beach began.

“Come on,” my brother called, crunching along the top of the bank.

The sky is always deepest blue after nights of wind and rain. I could see only blue and blue and Ned’s scrawny body, scrabbling away from me.

My brother began the usual introduction to our hunt, borrowed from our favorite program: “These are the adventures of Ned and Jamie.”

I joined in, laughing and putting on my best Star Trek voice. “Their continuing mission to explore strange new places, to seek out new life and junk on the beach. To boldly go—”

“Where no man has gone before,” Ned finished, and we chuckled as we kept on trekking.

Our sack was empty. Our eyes scanned the shoreline. Ned’s thin plimsolls kicked through the flotsam.

“Get off,” he said to a strand of brown seaweed that clung to his leg. He shook it till a coughing fit took over.

The gulls crawked above us. Maybe if I’d listened carefully, I’d have heard them call a warning. Beware.

When Ned was done, I knelt and peeled the weed from his bony ankle. “Home? We could try again later,” I said. I didn’t want to go home, but some things are more important than what I want.

Ned pulled the face that said he was fine: eyebrows up, big smile drawn from ear to ear. “We haven’t got anything yet,” he said.

I eyed my brother, scratched my chin, then nodded.

We climbed back to the top of the bank. We stood a while, breathed the salty air and watched the cars, ferrying people on and off the island along the road parallel to the shore. Then our searching gazes followed the long curve of the beach to where the frothy sea met pebbles.

A fisherman, his long pole spiking up and out to the sea, stood within shouting distance. A couple, hand in hand, trudged towards us from the island. Apart from those few, the beach was ours.

We stared at a murky patch of browns and greens, beyond the fisherman. A tangled web of seaweed like that could hold treasure. Or it could be ten minutes wasted, picking through slime.

“Let’s do it,” Ned said.

We kept to the crest of the gravel wave, taking slow steps. The beach moved beneath our feet, stones running away down each side, toward the English Channel on our left and Weymouth Harbour on our right.

“Mornin’,” the fisherman called as we passed above him.

“Morning,” I said in my voice.

“Mornin’,” Ned said in the fisherman’s voice, deep and gravelly.

The fisherman turned away and shook his head as Ned giggled.

When we got to the patch, we saw the weeds were deep. They swamped our shoes as we used our feet to search, pushing the plants aside, uncovering the beach beneath. There were the usual nets and scraps of rubbish, plastic and glass and string.

I waded deeper, squelching through the murky brown till my left foot fell on something that was neither rock nor weed.

“Maybe something here,” I called, taking a step back.

Ned coughed toward me. I prodded with a rubber toe. It was soft, fleshy. I pushed the weeds aside. Beneath was dark brown, smooth and shimmering.

“What is it?” Ned said at my elbow.

I crouched and put a finger to our find. Smooth to the eye but some roughness to the touch, like skin. I pushed harder and felt movement beneath.

“It’s alive,” I hissed at my brother. “Maybe another seal.”

Ned lowered himself beside me and we gently plucked away the layers of seaweed. The brown skin became scaled with green and red in one direction and a deeper brown—almost black—the other.

“Some sort of fish?” Ned whispered.

We pulled at the weeds, uncovering a rectangle of flesh, smooth at one end, scaled the other. It’s the creature’s back, I thought. This gave way to limbs and joints not like a fish’s. They were tiny, no longer than a baby’s. They looked shrunken, connected to long hands and feet—as long as Granddad’s, longer than most men’s. But where Granddad’s hands were wide fillets, these were slim and the bones beneath stick-thin.

Ned and I were silent. The sea fell silent. Above, the seagulls no longer spoke. Maybe they stared down too. A few strands of green and brown weed remained, where a head should be, could be.

“Wait,” I hissed as my brother reached forwards. “What is it?”

Ned grinned. “Let’s find out.”

My heart hammered. I wanted to pile the seaweed back over our find, turn and crunch away to discover old shoes and maybe that missing spoon. I wanted things to stay as they were.

But my brother wanted adventure. He always did. He pulled back the last thin fronds.

My stomach rose and stopped my breath. I was filled with terrible fear and thunderous excitement.

I’d never seen a head like this. The creature was on its side. Its eyes were human in shape, but bigger, bulbous beneath the closed lids. The nose was the small button nose of a child. There the human ended and the fish began. Its mouth was wide, stretching round from one side of the face to the other. Below this and the long narrow jaw were closed gills. On the top, where hair should have been, was a row of three pronged fins. No ears.

We crouched and stared as the tiny back rose and fell and the creature breathed long, silent breaths.

With my eyes wide and my heart pounding against my chest, like one of the massive drills Dad used at the quarry, I glanced at my brother. Ned’s face was alight with excitement.

I looked back to the creature. Neither of us spoke.

We stared as an eye cracked open, an eye as black as the deepest sea, and one of those long, thin hands shot out and grabbed Ned’s wrist. Our creature pulled itself toward him with the faintest croak and perhaps a flickering of recognition.

We both screamed. Ned wrenched away and we fell back into the mess of slimy weeds. The creature fell back too. And the eye closed.