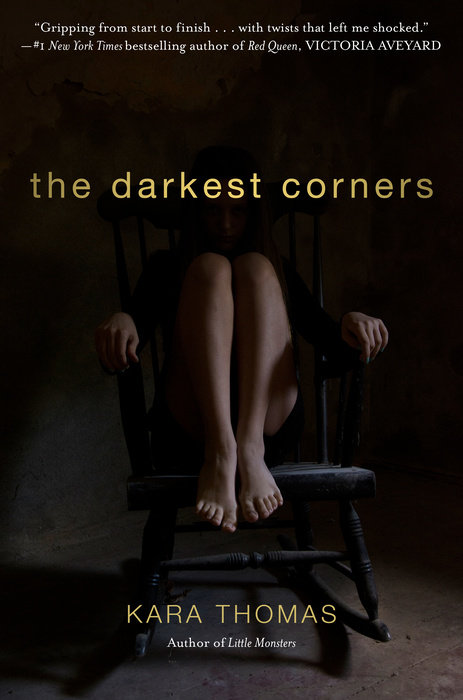

The Darkest Corners

Author Kara Thomas

"Gripping from start to finish . . . with twists that left me shocked."—Victoria Aveyard, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Red Queen

For fans of Gillian Flynn and Pretty Little Liars, The Darkest Corners is a psychological thriller about the lies little girls tell, and the deadly truths those lies become.

There are secrets around every corner in Fayette, Pennsylvania. Tessa left when she was nine and has been trying ever since not to think about what happened…

"Gripping from start to finish . . . with twists that left me shocked."—Victoria Aveyard, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Red Queen

For fans of Gillian Flynn and Pretty Little Liars, The Darkest Corners is a psychological thriller about the lies little girls tell, and the deadly truths those lies become.

There are secrets around every corner in Fayette, Pennsylvania. Tessa left when she was nine and has been trying ever since not to think about what happened there that last summer.

She and her childhood best friend Callie never talked about what they saw. Not before the trial. And certainly not after.

But ever since she left, Tessa has had questions. Things have never quite added up. And now she has to go back to Fayette—to Wyatt Stokes, sitting on death row; to Lori Cawley, Callie’s dead cousin; and to the one other person who may be hiding the truth.

Only the closer Tessa gets to what really happened, the closer she gets to a killer—and this time, it won’t be so easy to run away.

And don't miss Kara's next "eerie and masterly psychological thriller" Little Monsters—on sale now (SLJ)!

An Excerpt fromThe Darkest Corners

Chapter One

Hell is a two-hour layover in Atlanta.

The woman to my right has been watching me since I sat down. I can tell she’s one of those people who take the sheer fact that you’re breathing as an invitation to start up a conversation.

No eye contact. I let the words repeat in my head as I dig around for my iPod. I always keep it on me, even though it’s a model that Apple hasn’t made for seven years and the screen is cracked.

Pressure builds behind my nose. The woman stirs next to me. No eye contact. And definitely do not--

I sneeze.

Damn it.

“Bless you, honey! Hot, isn’t it?” The woman fans herself with her boarding pass. She reminds me of my gram: she’s old, but more likely to be hanging around a Clinique counter than at the community center on bingo day. I give her a noncommittal nod.

She smiles and shifts in her seat so she’s closer to my armrest. I try to see myself through her eyes: Greasy hair in a bun. Still in…

Chapter One

Hell is a two-hour layover in Atlanta.

The woman to my right has been watching me since I sat down. I can tell she’s one of those people who take the sheer fact that you’re breathing as an invitation to start up a conversation.

No eye contact. I let the words repeat in my head as I dig around for my iPod. I always keep it on me, even though it’s a model that Apple hasn’t made for seven years and the screen is cracked.

Pressure builds behind my nose. The woman stirs next to me. No eye contact. And definitely do not--

I sneeze.

Damn it.

“Bless you, honey! Hot, isn’t it?” The woman fans herself with her boarding pass. She reminds me of my gram: she’s old, but more likely to be hanging around a Clinique counter than at the community center on bingo day. I give her a noncommittal nod.

She smiles and shifts in her seat so she’s closer to my armrest. I try to see myself through her eyes: Greasy hair in a bun. Still in black pants and a black V-neck--my Chili’s uniform. Backpack wedged between my feet. I guess I look like I need mothering.

“So where you from?” she asks.

It’s a weird question for an airport. Don’t most people ask each other where they’re going?

I swallow to clear my throat. “Florida.”

She’s still fanning herself with the boarding pass, sending the smell of sweat and powder my way. “Oh, Florida. Wonderful.”

Not really. Florida is where people move to die.

“There are worse places,” I say.

I would know, because I’m headed to one of them.

I knew someone was dead when my manager told me I had a phone call. During the walk from the kitchen to her office, I convinced myself it was Gram. When I heard her voice on the other end, I thought I could float away with relief.

Then she said, “Tessa, it’s your father.”

Pancreatic cancer, she explained. Stage four. It wouldn’t have made a difference if the prison doctors had caught it earlier.

It took the warden three days to track me down. My father’s corrections officer called Gram’s house collect when I was on my way to work.

Gram said he might not make it through the night. So she picked me up from Chili’s, my backpack waiting for me on the passenger seat. She wanted to come with me, but there was no time to get clearance from her cardiologist to fly. And we both knew that the extra ticket would have been a waste of money anyway.

Glenn Lowell isn’t her son. She’s never even met the man.

I bought my ticket to Pittsburgh at the airport. It cost two hundred dollars more than it would have if I’d booked it in advance. I nearly said screw it. That’s two hundred dollars I need for books in the fall.

You’re probably wondering what kind of person would let her father die alone for two hundred dollars. But my father shot and nearly killed a convenience store owner for a lot less than that--and a carton of cigarettes.

So. It’s not that I don’t want to be there to say goodbye; it’s just that my father’s been dead to me ever since a judge sentenced him to life in prison ten years ago.

Chapter Two

Maggie Greenwood is waiting for me at the arrivals gate. She’s a few shades blonder and several pounds heavier than she was the last time I saw her.

That was almost ten years ago. I don’t like thinking about how little has changed since then. The Greenwoods are taking me in like a stray cat again. Except this time I’m well fed. I’m on the wrong side of being able to pull off skinny jeans. Probably all those dinner breaks at Chili’s.

“Oh, honey.” Maggie scoops me to her for a hug with one arm. I flinch but force myself to clasp my hands around her back. She grips my shoulders and gives me her best tragedy face, but she can’t help the smile creeping into her lips. I try to see myself through her eyes--no longer a bony, sullen little girl with hair down to her waist.

My mother never cut my hair. Now the longest I keep it is at my shoulders.

“Hi, Maggie.”

She puts an arm on the small of my back and herds me out to where she’s parked. “Callie wanted to come, but she had to get an early night.”

I nod, hoping that Maggie doesn’t sense how her daughter’s name inspires a sick feeling in my stomach.

“She has a twirling competition tomorrow morning,” Maggie says. I’m not sure who she’s trying to convince. I know it’s all bullshit and Callie wouldn’t have come if Maggie had dragged her.

“So she’s still into that?” What I really mean is, So people actually still twirl batons and call it a sport, huh? But I don’t want to be rude.

“Oh, yeah. She got a scholarship.” Maggie’s grin nearly cuts her face in half. “To East Stroudsburg. She’s thinking of majoring in exercise science.”

I know all this, of course. I know who Callie is still friends with (mostly Sabrina Hayes) and what she had for breakfast last week (cinnamon-sugar muffin from Jim’s Deli). I know how badly Callie is dying to get out of Fayette (pronounced Fay-it, population five thousand) and that she already parties harder than a college freshman.

Even though I haven’t spoken to her in ten years, I know almost everything there is to know about Callie Greenwood. Everything except the thing I desperately need to know.

Does she still think about it?

“Your grandmother told me you decided on Tampa?”

I nod and lean my head against the window.

When I told Gram I’d gotten into the University of Tampa, she said that I had better think real hard about going to college in the city. Cities chew people up and spit them out.

As Maggie gets off at the exit for Fayette, all I can think is that I’d rather be chewed up and spit out than swallowed whole.

Maggie pulls up outside a white, two-story farmhouse that was twice as big in my childhood memory. We shut the doors of the minivan, prompting the dogs next door to flip out. It’s almost one in the morning; in a few hours, Maggie’s husband, Rick, will be getting ready to start his bread delivery route. I feel bad, wondering if he’s waiting up to make sure Maggie got home okay. That’s the kind of husband he is.

My dad was the kind of husband who’d make my mom wait up, sick with worry, until he stumbled in smelling like Johnnie Walker.

The dogs quiet down once we’re on Maggie’s porch, already tired of barking. Neighborhoods in Fayette wear their emotions like people do. The Greenwoods’ neighborhood is tired, full of mostly blue-collar families who are up before the sun. The type of people who eat dinner together seven nights a week, no matter how exhausted they are.

When I think of my old neighborhood, I think of anger. Of crumbling town houses squashed together so tightly, you can see right into your neighbor’s kitchen. I think of angry old men on their porches, complaining about the cable company or the Democrats or their social security checks not arriving on time.

The Greenwoods used to live in my old neighborhood. They moved a year before I left to live with Gram, which meant I couldn’t run down the street to play with Callie like I’d been doing since I was six.

Maggie unlocks the front door, and I immediately smell the difference. I want to ask her if she misses her old house as much as I do.

But of course she doesn’t. And after what happened in that house, it’s the type of question that will definitely make me unwelcome here.

“Are you hungry?” Maggie asks, shutting the door and locking it behind her. “I know they don’t give you anything on the plane anymore. There’s some leftover lasagna.”

I shake my head. “I’m just . . . really beat.”

Maggie makes a sympathetic face, and I notice all the lines that weren’t there ten years ago. She probably thinks I’m upset about my father dying.

The Tessa she remembers would have been upset. She would have cried and screamed for her daddy like she did the day the cops broke the front door down and led him out of the house in handcuffs.

Maggie doesn’t know that the old Tessa has been replaced with a monster who just wants her father to hurry up and die so she can go home.

“Of course you are.” Maggie squeezes my shoulder. “Let’s get you to bed.”

The sun comes up the instant I fall asleep.

I really need a shower, but I don’t know where the Greenwoods keep their towels. In the old house, they had a linen closet inside the bathroom. Instead of going downstairs and asking Maggie for a towel, I splash some water on my face and pat it dry with a hand towel.

I have trouble asking people for things. I’ve been this way for as long as I can remember, but I think it got bad when Gram brought me to Florida. Before she turned her office into a bedroom for me, I slept on a pullout bed. There were no blinds on the windows, so every morning at six, the sunlight streamed in and I couldn’t fall back asleep.

I started sleeping under the pullout bed, because it was dark there. Gram didn’t catch me for more than a month. The windows in my room have blinds now, but sometimes, when I can’t sleep, I find myself crawling under the bed and staring at the bedsprings like they’re constellations.

I didn’t even bother trying to fall asleep last night. When I’m done washing my face I find some Listerine under the sink and swish a bit in my mouth. No reason to redo the bun I slept in. What’s the point? There’s no way I’ll look worse than my father.

Maggie is making French toast when I get downstairs. A coffeemaker gurgles on the counter.

“Milk or cream?” she asks, gesturing to the mug she’s left out for me. I don’t have the heart to tell her I hate coffee.

I shrug. “Either is fine.”

Maggie tilts the pan and flips a slice of bread. “I tried to get Callie up, but she’s not feeling well.”

I sit down at the kitchen table. I heard Callie sneak in at three this morning. I’ll bet anything she’s hungover. Once Callie started high school, the red Solo cups in her Facebook pictures started popping up like mushrooms.

“She’s missing her competition.” Maggie frowns, adjusting the heat on the stove. “But I figure I’ll let her slide. It’s the summer.”

My muscles tense up as I realize this means that Callie probably won’t be able to avoid me all day. Especially not if her mother has anything to do with it.

I called Callie every day for a week once I got to Florida. Every time, Maggie answered. Callie was either at twirling practice, or riding bikes with Ariel Kouchinsky, or finishing up her homework. Maggie’s voice became more desperate and apologetic every day. She didn’t want me to give up.

Eventually my calls stretched out to once a week, then once a month. Then they stopped altogether.

This past year, Maggie called on my birthday and sent us a card for Christmas. She didn’t mention Callie either time.

Three years ago, I spotted Callie in the last place I thought she’d be: an online forum dedicated to discussing the Ohio River Monster murder trial. She made only one post. It was two lines, telling the other posters to shut up--what did they know about the case, they were a bunch of wannabe lawyers living in their moms’ basements. She signed off with Wyatt Stokes is a murderer and never came back to defend herself against the swarms of people demanding, Prove it.

I know it was Callie; she used the same username she’s used for everything since we were ten--twirlygirly23.

I created an account and messaged her. It’s me, Tessa. I’ve been reading this stuff too. She never responded.

In any event, she can’t be thrilled that I’m back to remind her of the worst summer of our lives.

Maggie flops a piece of French toast onto my plate. I look up and return her wan smile. We have to be at the prison by eight.

Fayette, Pennsylvania, looks worse during the day. Worse than I remember. Maggie stops at the Quik Mart on Main Street to get gas. Half the businesses are boarded up, or are hiding behind Closed signs that are probably gathering dust.

A big part of Fayette died with the steel industry in the early nineties. Before I was born, my father worked at a mill in the next town over. Now Fayette looks as if it were clinging on for dear life. Probably because everyone here is so goddamn stubborn. No one will let Jim’s Deli or Paul the Tailor go out of business.

The people who are left refuse to pack up and leave. But with any luck, their kids will.

It takes us half an hour to get to the county prison. I don’t realize my leg is jiggling until Maggie puts the car in park and sets her hand on my knee.

“Honey, are you sure you want to do this?”

Of course I don’t. “It’s fine,” I say. “We won’t stay long.”

Maggie flips her mirror down and puts on a fresh coat of petal-pink lipstick. I return her tight smile, and we walk side by side to the security gate. She slips her arm around my back and doesn’t pull away when my muscles tense.

Gram isn’t touchy-feely. For years, every night I’d linger in the hall, watching her do her crossword puzzle in the den while muttering the answers to the questions on Jeopardy! under her breath. I’d wait right there, like some pathetic affection beggar, until she’d finally look up at me. She’d nod and say, “Well, good night, kiddo.” And that was it.

I kind of have a thing with people touching me now. Maggie doesn’t seem to notice that my reaching into my bag for my phone is really my way of trying to wriggle away from her.

“They’ll probably make you leave that up front.” She nods to my phone. “And hospice . . . they may not let me go in with you.”

I swallow away the bitter taste the coffee has left in my mouth. I guess I should be getting sad right about now, weighed down with memories of my father. Instead, I’m curious. I wonder what he looks like, whether his skin is rice-paper thin and sunken around his high cheekbones. In my memory, he was always healthy. None of us ever went to the doctor; my mom never liked them, and my dad swore that there was no affliction a shot of whiskey couldn’t fix.