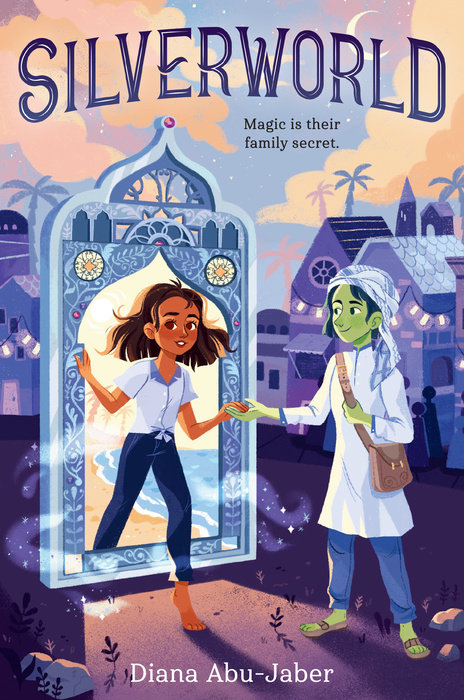

Silverworld

Sami would stop at nothing to save her Lebanese grandmother, Sitti. But family secrets lead to hidden worlds and more than just Sitti's fate hangs in the balance. The perfect read for fans of The Girl Who Drank the Moon.

Sitti, Sami's Lebanese grandmother, has been ill for a while, slipping from reality and speaking in a language only Sami can understand. Her family thinks Sitti belongs in a nursing home, but Sami doesn't believe she's sick at all. Desperate to help, Sami casts a spell from her grandmother's mysertious charm book and falls through an ancient mirror into a world unlike any other.

Welcome to Silverworld, an enchanted city where light and dark creatures called Flickers and Shadows strive to live in harmony. But lately Flickers have started going missing, and powerful Shadow soldiers are taking over the land.

Everyone in Silverworld suspects that Shadow Queen Nixie is responsible for the chaos, which is bad enough. But could Nixie be holding Sami's grandmother in her grasp too? To save Sitti and Silverworld, Sami must brave adventure, danger, and the toughest challenge of all: change.

An Excerpt fromSilverworld

I

“The moon was flat and white as a witch’s face.”

Teta leaned forward, her black eyes alight as she told her story.

“I could hear the hooves of the desert raiders as they crossed the sands. All the others slept soundly in their tents. I was all alone, twelve years old--the only one who knew they were coming!”

“Was your mother there? Why didn’t you wake her?” Sami whispered.

Teta threw out her arms dramatically: light glinted on her silver necklace and Sami caught a glimpse of one of the Bedouin tattoos that scrolled up her grandmother’s arms. “I tried! But we’d led our caravan all the way to Wadi Rum that day. Miles and miles over burning sand. Everyone was exhausted and sound asleep. And these were no ordinary bandits--the raiders were horrible brutes. I knew they would take everything--every horse and goat. And worse. I’d heard the whispers that they stole children, sold them into slavery. I shook my mother, I cried out, ‘The bandits are coming!’ All she did was mutter and roll back to sleep. Oh, it was awful--I was so scared.”

Sami leaned back on her grandmother’s soft silk carpet. The smell of jasmine and wild thyme faintly reached her from the shelves that lined the bedroom. “What did you do?” Even though she’d heard the story many times before, she still felt breathless.

For a moment, Teta’s lined face looked years younger, the light having shifted so her hair seemed to regain its black luster and the gray faded; she sat straighter, her neck lifting. She adjusted her sapphire ring. “I felt her.”

“Ashrafieh?” Sami whispered.

“My double.” Teta nodded slowly. “I’d always known she existed. My great-uncle had told me of her for years. But this was the first time I’d felt her--deep in my center.”

“What did she feel like?”

“Like courage. And cunning. A powerful current rising up from my center.” Teta placed one hand on her solar plexus and Sami touched her own chest, somehow feeling that same hidden something. “And a voice. Like it came from my own smartest self. Speaking from deep inside a hidden world. She said to me: Remember your training, Serafina. Call for an enchantment!”

“An enchantment--from the spell book, you mean?” Sami asked eagerly. “When can I see it?”

“Are you twelve yet?” Teta’s eyes widened.

“Practically! It’s just a few weeks--”

“When you’re twelve,” Teta cut in. “There are so many wonderful adventures ahead of you. As well as many . . . challenges,” she added. There was the briefest hesitation in her voice, then she waved her hand. “Let’s not rush into things.”

“But I’m ready now. I’ve been ready for ages,” Sami moaned.

“And you’re interrupting the story.” Teta shook her head. “Listen! I pushed back the tent flap--it was heavy, made of goat hair--very good for keeping out dust and noise. I always preferred sleeping under the night sky, but my mother wouldn’t let me. I stood--the raiders were coming so near I could see the smoke of the horses’ breath, the foam on their muzzles. I lifted my hands straight up to the stars. I was shaking, scared as a little chicken, but I’d heard my mother and great-uncle use the enchantment spell many times and I knew it by heart. I’d never spoken it out loud before, though, and I didn’t know if it would work for me--the magical ordering of words and sound. Still, I shouted it out with all my might.”

“And the bandits stopped,” Sami said, grinning.

Teta nodded. “Maybe twenty meters away. The ones who were jumping off their horses just flopped to the ground. Others fell asleep while they were still up on their horses. Their headscarves unwinding, all their gold teeth showing. They were dreadful, these monsters with their daggers drawn.”

“And their horses fell asleep too.”

“Yes,” Teta said with a wide smile. “I hadn’t learned my own magicking strength yet. I didn’t know how to control my spell casting. By then my great-uncle Kashmir had risen--he was still wrapping his headscarf over his hair. He ran out, looked at the fallen raiders, and said, ‘Ya Allah, child, you have the touch of the Ifrit!”

The Ifrit. Sami shivered with delight. Ifrit were magical sprites--sometimes called fairies, mermaids, angels, genies--that Teta said you could summon through dreams and visions and spells. They were creatures from the Other Worlds--places that Teta hinted at and promised to tell her about . . . someday. Always another day. “Did you tell him? Did he know about your guide, Ashrafieh?” Sami rolled forward onto her knees, the question urgent.

“Ashrafieh was a Flicker, not an Ifrit,” Teta reminded Sami.

“What’s the difference again?”

“Oh, the Ifrit serve no one, and they create as many problems as they solve! But a Flicker? Well now . . .”

But before Teta could say another word, the bedroom door swung open.

2

“Serafina? Oh dear. Will you look at that plate. Why aren’t you eating your eggs?” Aunt Ivory came into the bedroom, followed closely by Sami’s mother, Alia. Ivory pointed her long nose at the plate full of cold scrambled eggs on Teta’s nightstand. “Your daughter made them special--just the way you like them.”

For the past two years, Teta had eaten all her meals in her room and mostly refused to leave, except when her daughter dragged her out to the doctor. Easing back in her corner chair under the reading light, Teta said a few words to Alia in her nonsense language. Sami gritted her teeth in frustration. Why did her grandmother have to make things so much harder on herself?

Alia sighed and gave her sister-in-law an apologetic look. “She had a bad night,” Alia said. “I could hear her tossing and moaning. When I got up to check on her, she’d fallen back asleep.”

“It’s completely understandable.” Ivory lifted her eyebrows. “These sorts of things happen more often as we get older.”

These sorts of things. Leaning against the heavy wardrobe, Sami sighed deeply. She knew what her aunt was referring to--the fact that Teta didn’t seem to know how to speak clearly anymore. A year ago--actually, longer--Sami’s grandmother, her teta, had stopped talking. Well, she talked--she just didn’t use words that other people could understand. It happened slowly. First there would be one or two of these strange words that sort of popped up as she spoke. If you asked Teta what this or that meant, she would frown like you were being difficult and just keep talking. Over time, though, the nonsense words started to drown out the regular words. Sami used to beg her, “Why are you doing that? Can’t you just talk regular?”

The really weird part was that when they were alone, just the two of them in the room, Teta spoke perfectly clearly. No impossible words or nonsense. Sami told her mother, her brother, even her slightly horrible aunt, but none of them believed her. They said that was ridiculous--how could anyone deliberately keep up an act like that for so long? Sami couldn’t even understand it herself. All she knew was that whenever she asked Teta about the nonsense words, she didn’t seem to know what Sami was talking about. “I talk just fine,” she said indignantly. “It’s the others with a problem!”

Ivory bustled around Teta and picked up the plate of eggs. To Sami’s dismay, her aunt speared some eggs on a fork and held them up to Teta’s face. “Come now, dear, just a bite. For me.”

Teta made a big annoyed, abrupt gesture with her hands, as if she wanted to sweep Ivory out the door, but the back of Teta’s hand accidently hit the plate of eggs and sent them flying.

“Agh!” Ivory flinched. There was egg speckled all over the front of her silk blouse.

“Mother,” Alia snapped. She rushed to Ivory. “I’m so sorry! Oh, your beautiful blouse. Come, come--let’s see if we can’t get that out. . . .”

The two women hurried away, leaving Sami and her grandmother. Teta’s palms were pressed to the sides of her face. Her round black eyes turned to Sami. “Sseb-ssebb,” she garbled. “Aaal . . . feeek farab aam. . . .”

“It’s okay, Teta.” Sami crouched beside her grandmother and started picking up bits of egg. “It was an accident. They know you didn’t mean it.” At least, she thought, I hope they do. It broke Sami’s heart to see Teta looking hurt and upset. That’s what it feels like to not be able to defend yourself.

“Truly, just a stupid--a mistake. . . .” Teta stared at the door, returning to normal language again. “So clumsy.”

“But, um, Teta?” Sami interruped. “Seriously, you do have to eat something. I mean, I think Mom’s starting to get, like, worried about you and all.” A couple of months ago, she had noticed that her grandmother was eating less and less of the food they brought to her room. Sami tried to cover for her, taking a few extra bites before she returned the dishes to the kitchen, where her mother would sigh over them. But lately, Teta was eating so little that there was no disguising it--she looked thin and frail. And now Aunt Ivory had to get right into the middle of things. She’d started talking about sending Teta out to an old folks’ home ever since they’d gotten to Florida. Sami remembered the sour lemon expression on her aunt’s face as she brushed off egg crumbs.

Teta hummed and looked away in that aggravating I-don’t-want-to-talk-about-it way of hers--like Sami was the seventy-year-old and Teta was the one about to turn twelve. Sami sighed and placed the plate of spilled eggs on the nightstand. Voices reached her from downstairs. Through the walls, she could hear a sound of water rushing, maybe arguing? Then a door slammed.

“If you would just--talk normally to them!” Sami pleaded with her grandmother for the hundredth time. “They think you’re losing it, Teta.”

Ten minutes ago, Teta’s eyes had flashed with daring as she recalled her nights in the desert. Now her face looked pinched and white. Terrified. And at that moment, Sami had the weirdest, most chilling sensation--the feeling that Teta didn’t speak any differently when she was with her granddaughter, that she spoke the same way to Sami that she did with everyone else. Maybe Sami wasn’t supposed to be able to understand her grandmother any more than anyone else did. And yet for some reason she did.

With this thought in her head, she jumped up from the floor. “Excuse me, Teta, I’ve gotta go talk to Mom for a second.”

She felt her grandmother’s eyes on her, as if Teta wanted--needed--to tell her something. And yet lately it seemed harder and harder for Teta to tell even her stories. Her memory seemed increasingly misty and her handwriting had turned into an indecipherable series of scratches and dashes. Still, even though Teta had lapsed into silence, Sami could see some urgent, unspoken thought, right there on her grandmother’s face. And she knew Teta would open up only when she was good and ready to.

3

Sami went down the stairs cautiously, looking over both shoulders for her aunt, but there was no sign of Ivory. She found her mother sitting alone at the dining room table, her head in her hands. Alia looked up with a soft smile. “Hi, honey. Aunt Ivory went home. Um, to clean up.”

“Teta totally didn’t mean to do that, Mom. It was just a dumb accident. You know that.”

“Oh, I know. It’s too bad it was such a . . . messy one.” She laughed sadly.

Sami sensed there was something else that her mother wanted to say--something that she didn’t want to hear--but Alia was going to try to pretend that there wasn’t. “Hey, let’s think about your birthday plans,” her mom said, straightening up. “What do you say--let’s go up to Disney! You, me, and Tony. We’ve never gone--it’ll be fun!”

“You’re forgetting someone,” Sami said.

“Well . . . we really couldn’t take your grandmother along,” Alia said in a gentle voice. “She’s just--she’s unsteady--these days.”

Sami shook her head. “Teta is fine. She’s being weird about some stuff right now. But basically she’s really, really fine.”

Alia took a deep breath. In the silence, Sami could hear the soft tick, tick, tick of her brother’s basketball bouncing in the driveway, the scuffle of his feet. “Sami. We need to talk.”

Sami sighed as quietly as she could.

Alia went on: “Your grandmother--she isn’t fine, honey. When people get older, sometimes they start to have problems. They get frail, they can’t think clearly.”

“But she isn’t like that. I know, I know--she’s doing this weird thing with the way she talks. But you have to listen. When Teta and I are alone? She talks completely normally!”

Alia held her hands open. “Sami, if your grandmother has been speaking nonsense to me and the entire world--everyone but you--for over a year--is that behaving normally?”

Sami’s eyes prickled with tears; she gritted her teeth, refusing to cry. She didn’t know how to explain things to her mother so she’d understand. She barely understood it herself.

“I’d like to show you something.” Alia was already standing, removing an envelope from a stack of papers on the kitchen counter. She returned to the table and placed a brochure in front of Sami. It had a picture of a smiling white-haired woman with a nurse standing behind her, and said silver beaches manor. “Your aunt Ivory and I have been talking quite a bit and--well--sweetie--we both feel like Teta is starting to need more help. More than we can give her at home.”

“So you just want to, what? Stick her in one of those places? Where you don’t have to think about her?”

“Sami.” Now her mother was using her attorney voice. “This is about what’s best for Teta. She’s losing weight; she’s becoming a shut-in. I don’t like this any better than you do. In assisted care she’ll be able to socialize more, get therapy. They’re doing amazing things with dementia patients. . . .”

“Dementia?” Sami shook her head. “Teta doesn’t have dementia!” She kept her voice lowered, worried her grandmother would hear them, but she couldn’t help the tears that started to well up. “Why do you even listen to Aunt Ivory so much, anyway? Just because she’s Dad’s sister. Sometimes I think you care more about what she thinks than what Tony or I do.”

“Samara, you know that’s not true,” Alia said sternly.

“I don’t know anything!” Sami wailed, and ran out of the room.