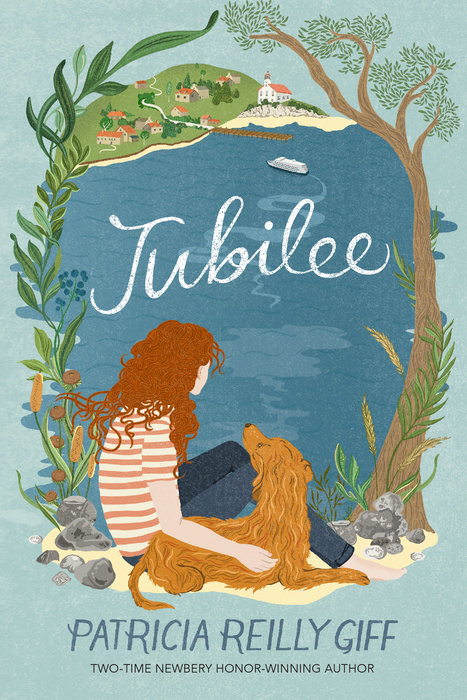

Jubilee

Newbery Honor–winning author Patricia Reilly Giff writes a tender, timeless story about a girl who stopped speaking long ago, and how she finds her way back to her voice. For fans of Listening for Lucca, Fish in a Tree, The Rules, and Mockingbird.

Judith lives with her beloved aunt Cora and her faithful Dog on a beautiful island. Years ago, when her mother left, Judith stopped talking. Now she communicates entirely through gestures and taps, and by drawing cartoons, speaking only when she’s alone—or with Dog.

This year, Judith faces a big change—leaving her small, special classroom for a regular fifth-grade class. She likes her new teacher, and finds a maybe-friend in a boy named Mason. But Jubilee’s wandering feet won’t stop until they find her mother. And now she discovers that her mother has moved back to the mainland, nearby. If Jubilee finds her, will her mother’s love be what she needs to speak again?

Judith’s cartoons, sprinkled throughout, add lightness and humor.

ILA-CBC Choices Reading Lists, Children’s Choices

Selected for the Kansas NEA Reading Circle Catalog

An Excerpt fromJubilee

Chapter 1

The last day of freedom. School tomorrow!

I sat on the edge of the wharf, legs dangling, holding my pad and pencils.

I drew a kid with red hair and green eyes, brows a little thick. I used quick lines for a pointy nose, and a squirrely nest of corkscrews for the hair.

It was turning out to be a girl like me, Judith Ann Magennis.

I tapped the pencil. What was missing?

Of course, the mouth.

My pencil hovered over the blank space. I tore the paper out of the pad, scrunched it up, and tossed it into the water.

Maybe like a mother who’d toss a kid away.

I hid my pad and pencils under a rock and slid down under the wharf to cool off. Water swished in, and I spread my hands like starfish to capture bits of shells.

Noise exploded above me—pounding on the wooden planks.

“I’m going to get you!” a voice yelled.

Me? I ducked under the water and came up dripping. I listened as feet barreled out to the deep end. Not me after all.

“Yeow!” someone yelled, and there was a huge splash.

I peered out from behind a splintery piling. What was going on?

“Serves you right, Mason!” the voice shouted. “Keep your hands off my books. Fingerprints all over them!”

Mason. I knew who he was. He was always a mess. Once I’d seen him rolling down the hill with his brother. He was on the bottom, then winning, on top, grass stains and mud all over him.

I glanced up through the spaces in the wharf and caught a glimpse of his brother, Jerry, who walked away, acting as if he owned the world.

In the water, Mason was a perfect cartoon, mouth open, sputtering, hair plastered to his head.

He swam around the side of the wharf and scrambled up onto the sand. Then he was gone.

I climbed up to the wharf and shook my hair dry. I loved this island. In the distance I could see the coast of Maine, a misty purple blur. And across from me were wooden walls that creaked and groaned when the ferry edged into the slip.

My mother had left on that ferry when I was a toddler, dropping me off at Aunt Cora’s as if I were a bundle of laundry.

She sent presents at Christmas and cards on my birthday, postmarked Oakdale, or Vista, or even Apple Valley. She signed them Mom, or Mother, or her name, Amber. She didn’t even know what to call herself.

A small boat sped by, sending up a curved wake. A man at the tiller turned off the motor and shouted back at me. “Hey, kid!”

I raised my hand to wave.

“Want a dog?”

Before I could move, he’d picked up a dog and dropped him into the water. “Can’t keep him.” He switched on the motor again and veered toward open water.

The dog struggled, paddling against the boat’s wake.

Poor dog.

Without thinking, I raced along the wharf and dived into the water.

There was a fierce riptide here. It made no difference to me. Gideon, the ferry boat captain, had taught me to swim by the time I was three.

“Swim with the tide, then around it,” he’d told me. “Don’t fight it.”

But the dog was fighting; I could see how tired he was. And soon he’d pass the end of the island and be swept out to sea.

I couldn’t speak, but I could certainly swim! I took long, sure strokes and kicked hard and evenly.

When I was close to him, I grabbed the narrow blue collar around his neck, but it came apart in my hand. I gripped a handful of his thick fur; then, with one arm around his neck, I swam back to shore.

Chapter 2

We lay there on the warm sand, Dog’s great dark eyes on me. When his fur was dried and combed, it would be close to the color of my hair, only lighter. Now he was shivering and cold, but more than that, he was afraid. I rolled in close to him, hugging him to me, warming him.

Did I want a dog? Oh, yes! And I was sure Aunt Cora would be glad to let me have him. I put my mouth against that matted fur and whispered, “You’re home, Dog. You’ll never have to see the terrible man on the boat again.”

He couldn’t hear me. There was only one place I could speak loud enough to be heard, and it was all the way up the hill, deep inside Ivy Cottage. But I felt the syrup of happiness being with this dog. He was feeling it too.

Then I remembered. Aunt Cora had sat next to me at breakfast this morning. In her slow, deliberate way, she’d begun: “You’ll be in a new class this year, a regular fifth grader, with thirteen boys and girls.”

No more special class? No more Mrs. Leahy and four other kids?

“Why shouldn’t you be in a regular class?” Aunt Cora said. “Because you don’t speak? You do other things.” She counted on her fingers. “You’re a great reader. You do math problems faster than I can. Your cartoons are spectacular.” She gave me a quick hug. “And most of all, you’ll be with more kids. You’ll make friends, Jubilee.”

That’s what she called me: Jubilee. “You’re a celebration!” she always said.

Some celebration!

Mrs. Leahy, my old teacher, called me Judy. Gideon, the ferry captain, called me Red because of my Pippi Longstocking hair. And Sophie’s five-year-old brother, Travis, called me No-Talk Girl.

Sophie.

Before first grade, Sophie and I were best friends. We dug tiny gardens together. We gathered stones and built houses that toppled into each other and made us laugh.

But one day, I’d heard Jenna ask, “How can you be friends with a weirdo like Judith, who doesn’t talk?”

So no more building, no more friend.

I stood now and squeezed water out of my shorts. Dog stood next to me, shaking himself, drops of water flying.

It was time to look at that fifth-grade classroom. I pulled my pad from under the rock, then started toward Shore Road.

Dog didn’t follow. His tail wagged uncertainly.

I went back and ran my hands over his head, down his back. We belonged together. I wanted him to know that.

I walked a few feet, and still he watched. Then, at last, he took a step toward me. A moment later, we loped along the road together.

In back of the school, I raised myself on tiptoe to see inside my new room. Desks were scattered every which way, and the chalkboard was dusty.

A new teacher danced across the front, her sandy hair in ringlets. She glanced toward the window, then went to the chalkboard and wrote her name: Ms. Quirk. Underneath she wrote WELCOME.

Had she seen me? I raised my hand to wave, but a ball smashed into the windowsill, just missing me. It bounced back against the cement and rolled away across the yard.

I turned. Mason! Why would he try to hit me? No wonder his brother was after him.

I gave Dog a pat, and then we ran past the school and tore up the dirt road toward Windy Hill and Ivy Cottage.

It really wasn’t a cottage anymore. The roof had caved in and vines covered the whole thing, so no one else knew it was there. It was almost mine.

Halfway there, Dog paused, nose twitching, tail high. What had he heard?

Was Mason following us? Then I saw what Dog had spotted on the ground: old branches were piled together with a row of stones in front.

Someone’s hiding spot.

A very messy one.

A face peered out at me: a mop of pale hair, blue eyes, and more freckles than I could count. It was Sophie’s little brother, Travis. He grinned, showing a missing front tooth. With a rustle of leaves, he disappeared again.

Dog sat in front of the hiding spot, whining in a let’s play voice, until Travis poked his head out again. His finger went to his lips. “Shhh.”

I nodded. He’d escaped from Sophie. He did that all the time. I’d hear her calling, her voice loud, then whistling shrilly. Sometimes I’d hear him laughing.

“You can come in, No-Talk Girl,” he said. “It’s my best place. But it’s a secret. Sophie will make me go home and wash my face and say my numbers. She’s a bossy girl, and I’m not a baby, you know.”

Dog and I crawled inside. Next to Travis was a book with a torn cover, a bag of half-chewed orange slices, and a pencil and paper. “You can draw me while I read,” he said.

I smoothed out the paper and drew a cartoon—a boy with a swirl of a hair, laughing eyes, and an upside-down book—while he made up a story about a girl who didn’t speak.

Dog’s head went up again. Travis put his hand over his mouth.

Mason walked by, his feet crunching on old leaves. If he’d looked down he’d have seen us, but he kept going.

Why had Mason thrown the ball at me? Just mean, maybe. I’d stay away from him.

I signed the cartoon Judith Magennis, handed it to Travis, and went with Dog to hang out at Ivy Cottage.