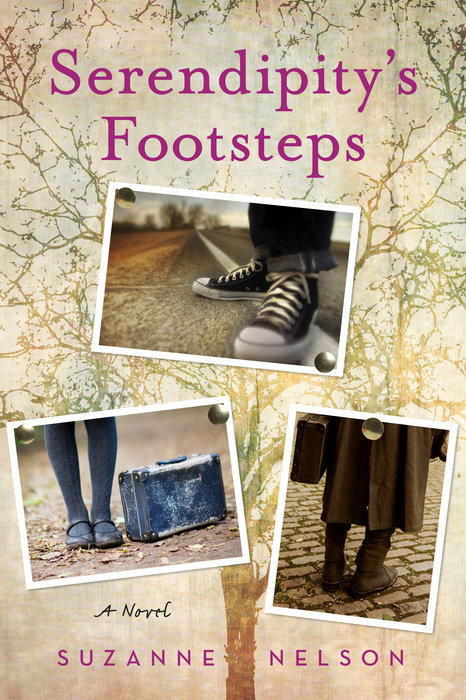

Serendipity's Footsteps

Author Suzanne Nelson

Serendipity's Footsteps

From Nazi Germany to a modern-day orphanage in the American South, three girls separated by decades and thousands of miles are about to give up when a single pair of shoes binds them all together.

Dalya is the daughter of a cobbler in 1930s Berlin, and though she is only fifteen, she knows she will follow in her father’s footsteps. When she is forced into a concentration camp one violent November night, she must…

From Nazi Germany to a modern-day orphanage in the American South, three girls separated by decades and thousands of miles are about to give up when a single pair of shoes binds them all together.

Dalya is the daughter of a cobbler in 1930s Berlin, and though she is only fifteen, she knows she will follow in her father’s footsteps. When she is forced into a concentration camp one violent November night, she must leave behind everything she knew and loved.

Ray is a modern-day orphan, jagged around the edges in every possible way. She sees an impulsive escape to New York as her only chance at happiness; there, she knows she’ll be able to convert her sorrows into songs.

Pinny is an unwavering optimist and Ray’s unintended travel companion on her passage to a new life. She inherited from her eccentric mother a fascination with shoes as a means of transformation and expression.

A single pair of shoes entwines these lives. How these women connect across different times and places is an unforgettable story of strength, love, bravery, memory, and the serendipity that binds us all together.

An Excerpt fromSerendipity's Footsteps

November 9, 1938

Berlin, Germany

Dalya

“It’s time.”

In a hushed tone, gentle but panicked, those were the words her mother spoke as the first tinkling of shattered glass came in the distance. She’d been looking out the window of their upstairs apartment, keeping watch, as she’d done each night for weeks now. Most nights, nothing of much importance happened. But today, Dalya had been sent home from school early. There were whispered rumors of something awful coming, though no one knew exactly what or when. As Dalya biked home that afternoon, dread crept through the streets of the West End, forcing her schoolmates inside long before dusk.

Now her mother turned from the window, her face waxen.

“They’re coming,” she said. “I’ll stay with your brother and sister. You go get your father from the shop.” She grabbed Dalya’s coat, mittens, and scarf from the coatrack. Quickly, she tucked several rolls of bread and a hunk of cheese into a hole she’d made days before in the lining of Dalya’s coat.

Dalya slid on the coat, the lumps of bread pressing…

November 9, 1938

Berlin, Germany

Dalya

“It’s time.”

In a hushed tone, gentle but panicked, those were the words her mother spoke as the first tinkling of shattered glass came in the distance. She’d been looking out the window of their upstairs apartment, keeping watch, as she’d done each night for weeks now. Most nights, nothing of much importance happened. But today, Dalya had been sent home from school early. There were whispered rumors of something awful coming, though no one knew exactly what or when. As Dalya biked home that afternoon, dread crept through the streets of the West End, forcing her schoolmates inside long before dusk.

Now her mother turned from the window, her face waxen.

“They’re coming,” she said. “I’ll stay with your brother and sister. You go get your father from the shop.” She grabbed Dalya’s coat, mittens, and scarf from the coatrack. Quickly, she tucked several rolls of bread and a hunk of cheese into a hole she’d made days before in the lining of Dalya’s coat.

Dalya slid on the coat, the lumps of bread pressing awkwardly against her side. She nearly argued that it was a ridiculous precaution. The Gestapo had made their searches for weapons and contraband a dozen times before. Yes, they’d arrested Herr Rozen, the neighborhood butcher, after he was caught selling kosher meat. But after they closed his shop, they released him. What was so different about tonight? Still, the fear in her mother’s eyes kept her silent.

Her mother slipped her rings from her hand, then set them in Dalya’s palm. “Remember what we talked about.”

“But I’m sure it’s nothing--”

Her mother raised a finger to Dalya’s lips, stopping her. “They set fire to the Schellers’ shop!” she whispered, making sure only Dalya would hear. “They’re destroying everything!”

“What?” Terror flared inside her. This was different from the boycotting of their store, from the ugly vandalism happening more and more often. It had never been like this.

“Tonight, liebchen, everything begins.” Her mother hugged her fiercely. “Beeil dich!” she whispered. “Hurry now! There isn’t much time.”

Dalya glanced at David and Inge, who were sitting at the table eating their abendbrot. Her mother was ushering them into their coats between mouthfuls, filling their pockets and liners with rolls, too.

“Where are we going?” David protested, shoveling in one last bite. “I’m not finished yet!”

Dalya swallowed thickly, her blood humming in her ears. Poor Inge and David. At five and seven, the most frightening thing they’d known so far was the prospect of losing their suppers.

“And Dalya promised me and Dolly a story,” Inge said, pouting as she hugged her doll. With chubby cheeks and tiny features, she still looked babyish, and she was doted on because of it. Her mother coddled Inge more than she ever had Dalya, letting her throw tantrums without punishment and escape household chores. Nearly every night, while her mother helped her father clean the store after closing, Dalya put Inge to bed with a story. At times, she resented being pulled away from the store, especially when Inge was difficult. To ease her own impatience, she wove shoes into every story she told so they’d never be far from her thoughts. When Inge’s eyes finally fluttered closed, though, Dalya loved the sweetness of that small hand resting in hers.

David was Inge’s playmate, but also her nemesis, and now he smiled mischievously at her. “I’m going to give your dolly a trim,” he said, making his fingers look like scissors. Inge shrieked and leapt behind their mother, cuddling her doll protectively.

“I’m sure we’ll be right back,” Dalya said. “And then, Inge,” she added, grinning, “maybe we’ll give David a trim of his own.”

David’s eyes widened as Dalya lunged to tickle them both, but then her mother snapped, “This is no time for teasing.”

Dalya straightened at her harsh tone. “I was trying to help,” she said, but her mother hustled her to the door with a stern “Go.”

With Inge and David looking after her in surprise, she ran downstairs and into the back of their shop. As soon as she stepped through the door, the musky scent of leather engulfed her. It was the smell that had encompassed her whole existence as a young child, when she’d sat behind the shop counter eating potato knishes and watching her mother and father work. It was the scent of the familiar, of the loved--a scent she hoped would be with her for life. Because just as her mother and father made shoes, so, she hoped, would she. Someday, she and her husband would run this store together, like her parents did now.

Her father sat on his stool, his lapstone perched across his thighs, hammering a sole. He glanced up absently with a half smile, an expression that he wore when he was thoroughly absorbed in his task.

“Vati,” she croaked. “Vati, they’re coming. Muti says they’re burning shops.”

His smile collapsed, his ruddy cheeks sallowing. He stood, and the sole he’d been holding fluttered to the floor. Peering out the large front window, he gasped. “But this . . . this is madness. . . . They can’t!” Sharp cracks split the air, making them both jump. “Gunshots,” he whispered. He rushed to the cash drawer and emptied it.

She ran to her father’s side, and together, they pushed the wooden display shelf across the floor, exposing an almost imperceptible panel cut out of the wallpaper. Her father slid a pocketknife into the seam and lifted the panel out from the wall, revealing a safe.

“I’ll take care of this,” he said. “You do as your mother wanted.”

Dalya nodded, then grabbed the tin box from its place at the back of the supply closet. She raised the lid, and there inside, exactly as she’d left them last night, were the shoes . . . her shoes. Even with her growing panic, she thrilled to look at them. The first pair of shoes her mother had let her make on her own, start to finish. She’d sketched them out in her notebook last spring. Normally, she hoarded her drawings, guarding them from her mother. Her mother doled out more criticism than compliments, constantly correcting Dalya’s handiwork, making her redo the stitching on an outsole or reconstruct a vamp that wasn’t absolutely perfect.

“The shoe,” her mother always said, “must be a second skin. It’s a resting ground for the foot, something that beautifies and cushions. A person must never feel they’re wearing the shoe. If it rubs, scrapes, or pinches the toes, then it is not well made.”

But when Dalya had first pictured these shoes in her mind, she’d sensed the inspiration was rare and should be put down on paper before it flittered away. She’d felt such intense affection for these shoes that she hadn’t wanted her mother niggling over them, picking them apart. One day, though, she’d left her notebook open at the kitchen table, and she’d come home from school to find her mother bent over the sketch of the shoes, studying it intently.

Dalya waited, holding her breath.

“This shoe . . .” Her mother traced the silhouette with a finger. “This shoe is fine. You may make this one.”

Her father made a new last for the shoe, one carved from oak and shaped from Dalya’s own foot. Dalya chose a champagne satin with a rosy sheen for the upper and spent hours embroidering it with a delicate floral design. Her mother rarely consented to such extravagance, but surprisingly, she had let Dalya choose the finest fabrics and materials for her shoes. A Louis heel paired with a rounded toe box gave the shoe a soft femininity, and a border of tiny pearl beading embellished its throat. Finally, the satin laces added above the vamp tied across the slight arch at the top of the foot like a silken bridge. Once, Frau Kaufmann had stopped by and seen Dalya working on the shoes. She’d wanted to buy them on the spot. Dalya had blushed with pride, but her mother said simply, “These shoes are for my Dalya. Someday, she will be married in them.”

Just like that, the fate of Dalya’s shoes was decided. Her mother had made the statement as if it were fact, and Dalya hadn’t even minded. As soon as she heard the words, Dalya knew they were true. She had no prospects for a husband and, at fifteen, no wish for one for years to come. Still, she knew that someday, when she found a young man worthy of the shoes, she would wear them for him on their wedding day.

Now, with the sound of shouts and shattering glass from the street outside growing louder, more insistent, Dalya lifted the right shoe from the metal box. She turned it over, then carefully tilted the heel back from the outer sole. A hidden hinge her mother had designed allowed the seat of the heel to pull away from the sole to reveal the tiny compartment hollowed out of its top.

The hiding place had been her mother’s idea.

“A place the Nazis will never look,” her mother had said. “We hope for the best but must plan for the worst.”

Dalya took her mother’s rings from her pocket. The wedding band was a muted gold, and the engagement ring had a center stone with six smaller diamonds surrounding it. The diamonds often threw rainbows around the shop while her mother worked. Dalya had never seen her take off her rings before, and she shuddered to think what would let her mother bear being separated from them. She tucked the rings carefully into the heel next to the thin piece of paper she’d slipped inside weeks ago, then sealed the heel with glue.

The shouts in the street had become deafening, and Dalya’s father was hurrying through the store toward her.

“You must finish!” His voice was stiff with urgency. “They’re next door already.”

She laid the shoes back in the tin box. Her quivering fingers struggled to latch the lid. When it was fastened, she bent over the floorboards behind the counter, scrambling for the right one. She edged her fingernail into a crease and eased the board up, then tucked the box underneath. The second the floorboard slapped back into its slot, her father was there with his hammer, nailing it into place. It was on this very board, over the shoes she’d lovingly handcrafted, that Dalya stood when the two soldiers burst into the store.

The first thing she noticed was the red band with its black swastika on their gray uniforms. The sight of it withered her insides. The second was their boots. Polished to a glossy black, they were meant to impress, or intimidate. When Dalya looked at them, she saw a garish, skeletonized reflection of her face in the gleaming toes. And she suddenly hated the boots--hated them for bringing terror into this place she loved.

“We are looking for Herr Amschel,” the taller soldier said.

Her father nodded. “You’ve found him.”

The soldier stepped forward. “You are charged with being an enemy of the state. You and your family must come with us.”

“An enemy of the state?” Dalya locked eyes with the soldier, her heart striking against her ribs. “That is ridiculous.” His mouth thinned into a line. “My father has done nothing--”

“Shhhhh.” Her father gave her arm a squeeze.

She waited for him to protest, to plead his innocence. But her father, who had never broken eye contact with any man in his life, bowed his head to stare at the floor.

“Of course we will come with you,” he said in a polite, supplicating tone foreign to Dalya. “Please, I need a few moments to collect my wife and children.”

“Three minutes,” the tall soldier snapped.

“Thank you.” Her father bowed his head appeasingly, then pulled Dalya up the back stairs, clutching her hand so firmly that it ached.

“They can’t arrest you,” Dalya whispered. “What have you done?”

Her father stopped on the top stair, his face pained. “We are Juden. That alone is a crime to them.”

Opening the door to their small apartment, they found her mother, brother, and sister waiting. Gone were David’s playful teasing and Inge’s melodrama. Their eyes were wide and scared.

“We must go with them, but we will be back.” Her father kissed her mother on her forehead. “This will pass soon enough.”

Together, they walked downstairs to the shop, where the soldiers waited. The tall one stood near the counter, inspecting her father’s shoemaking tools, his lips curled in distaste. And then Dalya saw it--the pot of glue she’d been using earlier, perched on the counter, within perfect range. As she moved past the soldier, she pretended to stumble. She grabbed the counter to catch herself, deftly knocking the pot off the edge.

It overturned, pouring thick yellow glue all over the soldier’s boot.

“Schwerfällig!” the soldier growled. “Clumsy!”

Dalya covered her mouth, feigning horror. “I am so sorry,” she said. “I slipped.”

Her mother yanked her out of the soldier’s way. “Forgive her,” she said quickly. “She is just a young, absentminded girl.”

The soldier’s eyes burned, and he raised his hand, ready to strike. But a wail broke from Inge’s throat, surprising him. The hand dropped.

“Take them outside,” he said through clenched teeth. “Now.”

Dalya was hurried out, her mother risking one scolding glance in her direction that said she knew the glue wasn’t clumsiness. But Dalya didn’t care. She was glad she’d done it. Even if his hand had come down on her, she’d still have been glad. There was a hidden smile inside her as she watched the soldier trying in vain to wipe the glue from his boot. Finally, he gave up and joined them outside, his face a blister of rage.

“Get in line.” He nodded toward the other side of the street, where their neighbors stood in one trembling huddle. There were the Buttenheims, the Felsbergs, the Rozens. There was Aaron Scheller, one of her classmates, with his mother, father, and little sister. Chava Scheller was her mother’s best friend, and their families often got together for Shabbos dinner. Dalya had known Aaron since the two of them were toddlers. As a child, he’d often followed her from room to room like a parched animal following a cloud. She’d never tried to hide her annoyance with his devotion. She remembered putting on countless puppet shows and dance performances, laughing and twirling around him as he sat watching somberly on the floor. Though part of her appreciated the attention, there was always too much adoration in his penetrating gaze. It vexed her that he granted it so easily when she felt she hadn’t earned it. Now here he was, watching her again with those same inquisitive chestnut eyes.

Dalya stepped into the street, glass crackling under her shoes. Shopwindows up and down Kurfürstendamm sat gaping, their glass shattered. The street was one of the busiest in the Charlottenburg district, usually bustling with shoppers, but tonight it was desolate and broken. Whimpers and sobs from neighbors she’d known most of her life, people she’d never seen cry, were an undercurrent to screams and gunshots echoing from the surrounding streets.