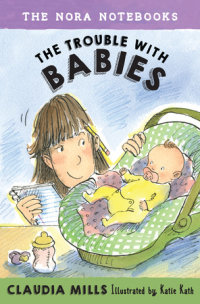

The Nora Notebooks, Book 2: The Trouble with Babies

Author Claudia Mills Illustrated by Katie Kath

The Nora Notebooks, Book 2: The Trouble with Babies

The Nora Notebooks, Book 2: The Trouble with Babies is a part of the Nora Notebooks collection.

"The thought-provoking reflections on personality and growth add insight and discussability."--The Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books

Fourth grade scientists are not meant to be babysitters. The second book in the Nora Notebooks finds Nora Alpers in unfamiliar territory.

Nora Alpers has just become a ten-year-old aunt. To prepare for the new arrival, Nora has been writing down baby-related facts in her special notebook, just like she does with her favorite subject: ants. She…

"The thought-provoking reflections on personality and growth add insight and discussability."--The Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books

Fourth grade scientists are not meant to be babysitters. The second book in the Nora Notebooks finds Nora Alpers in unfamiliar territory.

Nora Alpers has just become a ten-year-old aunt. To prepare for the new arrival, Nora has been writing down baby-related facts in her special notebook, just like she does with her favorite subject: ants. She likes the idea that someone who studies the A-N-T is also an A-U-N-T, even though she doesn’t know anything about taking care of babies.

A new family member isn’t the only thing stressing Nora out. At school, Nora has to write journals in the voice of a pioneer on the Oregon Trail and prepare for the annual science fair. Science is normally Nora’s best subject—until Nora ends up being paired with science-hating, cat-obsessed Emma! How will Nora ever learn to be a good aunt if she’s trying to survive the Oregon Trail and arguing against Emma’s unscientific science-fair ideas?

Readers will welcome the return of Nora who Publishers Weekly called “delightful[ly] enterprising” in a starred review.

An Excerpt fromThe Nora Notebooks, Book 2: The Trouble with Babies

1

Nora Alpers didn’t believe in luck. She believed in the laws of science, which left no room for luck, good or bad. But right now, on this Wednesday morning in March, she felt as if either luck or the laws of science had turned against her. Otherwise, she wouldn’t be stuck with Emma Averill as her science-lab partner.

“What if we get electrocuted?” Emma wailed as Nora prepared to connect one end of a copper wire to the positive terminal of their dry-cell battery.

“We won’t,” Nora said, trying to keep her voice even.

“We could,” Emma shot back. “This is exactly how people get electrocuted--by doing dangerous things with electricity.”

“This isn’t dangerous!” So much for keeping an even tone. “No one in the history of the world has ever been electrocuted by a ten-volt battery.”

“Well, I don’t want to be the first!”

Nora sighed. She didn’t mind doing the experiment all by herself; in fact, she preferred it. And Emma was a nice enough person, one of the friendliest girls in their fourth-grade class. But Nora was tired…

1

Nora Alpers didn’t believe in luck. She believed in the laws of science, which left no room for luck, good or bad. But right now, on this Wednesday morning in March, she felt as if either luck or the laws of science had turned against her. Otherwise, she wouldn’t be stuck with Emma Averill as her science-lab partner.

“What if we get electrocuted?” Emma wailed as Nora prepared to connect one end of a copper wire to the positive terminal of their dry-cell battery.

“We won’t,” Nora said, trying to keep her voice even.

“We could,” Emma shot back. “This is exactly how people get electrocuted--by doing dangerous things with electricity.”

“This isn’t dangerous!” So much for keeping an even tone. “No one in the history of the world has ever been electrocuted by a ten-volt battery.”

“Well, I don’t want to be the first!”

Nora sighed. She didn’t mind doing the experiment all by herself; in fact, she preferred it. And Emma was a nice enough person, one of the friendliest girls in their fourth-grade class. But Nora was tired of explaining to Emma that they weren’t going to receive a fatal shock by sitting two feet away from a low-voltage battery.

“I hate electricity,” Emma moaned.

“You use electricity to charge your phone,” Nora said.

This was the same phone on which Emma showed the other girls countless videos of her cat, Precious Cupcake. Nora’s own pets, a few dozen ants in her ant farm, were as different from Precious Cupcake as pets could be.

“You use electricity for . . .” Nora tried to think of another of Emma’s favorite electric-powered gadgets. “For your hair dryer.” Emma’s golden curls obviously benefited from electric-powered hairstyling equipment, unlike Nora’s straight brown hair, which dried by itself without any electrical assistance.

“My cousin knows someone who had a friend who had a neighbor who was electrocuted when her hair dryer fell into the bathtub,” Emma said triumphantly, as if this were reason to avoid touching any wire in any science lab ever.

Nora sighed again.

Across the room, her friend Amy Talia was busily working away with Anthony Tobias, a pleasantly serious boy who played the violin. Both of them were managing to hook up a wire to a battery without any fuss.

On the other side of the room, Mason Dixon and Brody Baxter were working happily together. Somehow these two best friends had ended up in the same pod and had gotten to be science partners, too. Talk about luck! In the back of the room, Dunk Edwards was working with Sheng Ji, who had to be the unluckiest boy of all for ending up with Dunk as his science partner. At this moment, Dunk was poking a stray wire into Sheng’s somewhat chubby middle.

“Is Dunk electrocuting Sheng?” Emma asked nervously.

“The wire isn’t even connected to anything,” Nora pointed out. “It’s not conducting any electricity at all.”

Reassured, Emma giggled appreciatively at Dunk’s antics.

“Dunk!” Coach Joe called over to Dunk’s pod.

Coach Joe wasn’t a coach; he was their usually good-natured teacher who loved anything to do with sports the same way Nora loved anything to do with science.

Nora continued with the experiment, glad that Emma was distracted by watching Dunk redden under Coach Joe’s reprimand. Then Dunk poked the wire into Sheng’s tummy again, provoking more of Emma’s giggles.

At least Nora would be able to do her science-fair project all by herself. March was science-fair month at Plainfield Elementary School, so it was Nora’s favorite month of the school year. Now she had the delicious task of trying to decide what her project would be.

The obvious choice would be to do something involving the ants in her ant farm, but Nora had already done so many ant farm experiments over the past few months that she was ready for a change. Maybe her ants were ready for a change, too. Nora didn’t want them to live out their relatively short life spans as nothing but subjects of scientific experimentation.

After a few more minutes, Nora had completed the dry-cell battery experiment and written down the results in her science notebook. Nora loved notebooks: she loved having all her data neatly cataloged there, a record of her findings to save for the rest of the school year. Emma, who had done nothing on the experiment at all, copied every-thing Nora had written into her own notebook, which had a pink cover featuring a photo of a white kitten with an even pinker bow in its fur. Coach Joe had posted Dunk’s name on the chalkboard list labeled “Benched!” so Dunk was sulking. Science time was over.

“Huddle!” Coach Joe called out.

That was his word for an all-class meeting on the football-shaped rug in one corner of the classroom. Nora and Amy found seats on the floor next to Mason and Brody.

“I think our battery was a dud,” Mason said. “But then Coach Joe came over and made it work, so maybe we were the duds.”

“Or maybe Coach Joe is a battery genius,” Brody said.

Mason and Brody were inseparable even though they were complete opposites in personality. Mason always saw the glass as half empty; Brody saw it as half full. No, Nora thought: Mason saw the glass as bone-dry, and Brody saw it as overflowing. She herself was the kind of person who would want to measure the volume of water in the glass--in milliliters, of course, not ounces, because true scientists used the metric system--before coming to any conclusions about it.

“Science fair!” Coach Joe said once everyone was seated in the huddle, except for a scowling Dunk, who was still “benched” back at his desk in his pod.

Nora turned her full attention to her teacher.

“This year there are going to be a couple of differences from how you’ve done the science fair in the past,” Coach Joe began.

Nora wished she had brought her science notebook to the huddle so that she could take notes.

“Change number one,” Coach Joe said. “In the lower grades, the science fair was optional. You could choose whether to take a turn at bat or not.”

Nora had always done the science fair, but most of her classmates, including Amy, hadn’t.

“This year it’s mandatory. All of you are going to be working on a project to display at the fair two weeks from this Friday.”

Brody’s face brightened. Brody liked to do everything, although Nora couldn’t remember whether he had done a science-fair project in third grade or not.

Mason’s face darkened. Mason never liked doing anything.

Pouting, Emma raised her hand. “I don’t think that’s fair. Some people like science, and some people don’t. People who like science should get to do the science fair. And people who don’t like science shouldn’t have to.”

“In life, Emma,” Coach Joe said, “sometimes we have to do things we don’t want to do.”

Nora knew that Emma was the kind of girl who almost never had to do anything she didn’t want to do.

“In any case,” Coach Joe went on, “all of the fourth-grade teachers are in agreement on this one. And we’re in agreement on the second big change as well.”

Nora waited to hear what he said next.

“In the past, we’ve seen a lot of amazing science-fair projects.”

In all modesty, Nora thought her own science-fair projects had been pretty amazing, especially her third-grade project testing water quality from the creek that ran through the open space at the back of her house. It had won a blue ribbon at Plainfield Elementary and was one of the four projects from her grade selected to go on to the regional science fair.

“But,” Coach Joe said, “some of the projects have been too amazing.”

How could any science be too amazing? All of science was amazing when you let yourself think about it, which Nora did often.

“So amazing,” Coach Joe continued, “that the Plainfield Elementary student science fair was starting to seem more like the Plainfield Elementary parent science fair.”

Nora bristled. Her parents were both scientists, her nineteen-year-old brother was studying science right now at MIT, and her twenty-four-year-old sister was a scientist, too, although she was about to take off time from work to have a baby, due any day.

In preparation for being a ten-year-old aunt, Nora had started writing down baby-related facts in another special notebook she kept at home, where she saved fascinating information about ants and other marvels of the world. Now she was concentrating on finding facts about babies, like the statistic that a baby was born somewhere in the United States every eight seconds. Her father had told her that one.

But none of Nora’s scientist relatives had helped her with the science fair one little bit. She had done every project all by herself. Grown-ups never believed that kids could do awesome things without their help.

On the other hand, Nora did remember a couple of projects by kids in her class that looked as if they had been done mainly by their parents, like Dunk’s beautifully presented research on the effect of different materials on a magnetic field. Dunk had done that?

“So this year,” Coach Joe said, “we’re not going to be doing our science-fair projects at home with our parents. We’ll be doing them here at school. Of course, you may need to do some parts outside of the classroom for practical reasons, but we expect you to work without parental assistance.”

That was completely fine with Nora.

“And,” Coach Joe continued, “each of you will be working with a partner.”

Nora’s heart sank.

But it would be all right if she could work with Amy. Amy didn’t love science as much as Nora did--few people loved science as much as Nora did--but Amy wanted to be a vet when she grew up, and she was wild about animals. Nora wouldn’t mind doing a project on animal behavior with Amy. Nora’s parents were always telling her that science was collaborative. That meant that scientists cooperated with one another to achieve their results. Most grown-up scientists conducted their experiments in huge labs with lots of other people, not alone in their own houses.

Nora looked over at Amy. Amy’s eyes met hers with the same question. Nora answered it with a big grin, which Amy returned.

The Nora-Amy team would be unbeatable! With Amy as her partner, Nora would be sure to be picked for the regional science fair again this year.

“Because you’ll be doing your science-fair projects here at school during our science time,” Coach Joe went on to explain, “it will be easiest if you work with your current science partner.”

No!

Nora would have to work with Emma?

Mason and Brody were already high-fiving each other.

Amy and Anthony exchanged smiles. Anthony would be a good second-best choice as a partner for Amy. But as a partner for Nora, Emma would be the worst choice in the world!

Nora wanted to raise her hand in protest, echoing Emma’s comment from five minutes ago: “I don’t think that’s fair!”

But she knew already what Coach Joe would say in reply: “In life, Nora, sometimes we have to do things we don’t want to do.”

Maybe Nora should start believing in luck.

Because right now her luck was terrible.

Approximately 130 million babies are born each year. That means that 4 babies are born in the world every second. A baby is going to be born in my family very soon. But I hope it’s not today. I have enough else to worry about right now!

2

As soon as Nora got home after school the next day, she could hear her mother talking on her cell phone. Nora’s parents were both professors at the university. Her mother was an astrophysicist, studying the rings of Saturn. Her father was a biochemist, studying extremely tiny molecules with extremely long names. But they worked in their home offices a lot, too.

Nora and Emma hadn’t talked yet about the science fair; they wouldn’t have science time in school again until tomorrow, Friday. But Emma certainly hadn’t squealed with rapture at the thought of being Nora’s partner, either.

“How far apart are they?” Nora’s mother said into the phone.

How far apart were what?

“Ten minutes?” her mother said. “Have you called your doctor? What did she say?”

Nora’s mother waved hello to her in a distracted way, mouthing the word Sarah.

Nora should have guessed that her mother was talking to her sister about the baby, the baby, the baby. When the baby comes had become her mother’s favorite expression. It was fast becoming Nora’s least favorite expression.

When the baby comes, Sarah and the baby were going to stay at Nora’s house for a few weeks because Sarah’s husband, Jeff, was away on active duty as an air force pilot.

When the baby comes, Nora was going to become Aunt Nora. She liked the grown-up sound of her new name. And it was pleasing that someone who studied the a-n-t was also going to be an a‑u‑n‑-t. But she didn’t know anything about how to take care of babies, and surely an aunt shouldn’t be as clueless about babies as . . . as Emma was about batteries. But maybe some of the facts she was collecting about babies to write in her fascinating-facts notebook would come in handy.

When the baby comes, they were going to find out whether it was a boy or a girl. Sarah and Jeff still didn’t know; they didn’t want to know. That seemed ridiculous to Nora. If something was knowable, if all the doctors and nurses knew it, why would you want to be the only ignorant one? Nora wanted to know everything that could be known in the entire universe.

“I want it to be a surprise” was all Sarah would say.

Nora tuned back in to what her mother was saying on her end of the conversation.

“Yes . . . yes . . . Definitely . . . I’ll meet you at the birthing center as soon as I can get there.” Sarah lived about an hour’s drive away. “All right . . . Oh, sweetie . . . I’m leaving now.”

Clicking off the phone, her mother gave Nora a shaky smile.

“She’s starting to have contractions. Her doctor said to go to the hospital. So I’m heading there now. I’ll text Amy’s mom to see if you can stay with Amy until your dad finishes work. He has a late meeting.”

Nora liked spending time at Amy’s house, with Amy’s extensive menagerie: two dogs, two cats, two rabbits, and two parakeets. But she also thought she’d be fine at home by herself with her ants for company. Somebody who was about to become Aunt Nora could surely stay at home alone for an hour or two. But her mother was a worrier.