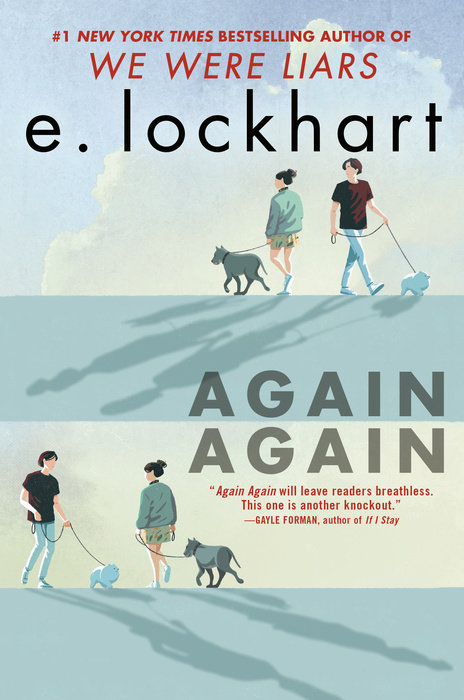

Again Again

Author E. Lockhart

Again Again

This twisty novel from the New York Times bestselling author of We Were Liars and Genuine Fraud asks: What if there were infinite universes and infinite ways to fall in love?

If you could live your life again, what would you do differently?

After a near-fatal family catastrophe and an unexpected romantic upheaval, Adelaide Buchwald finds herself catapulted into a summer of wild possibility, during which she will fall in and out of love a thousand times--while finally confronting the secrets she keeps, her ideas about love, and the weird grandiosity of the human mind.

A raw, funny story that will surprise you over and over, Again Again gives us an indelible heroine grappling with the terrible and wonderful problem of loving other people.

"Inventive, philosophical and romantic." --GAYLE FORMAN, #1 New York Times bestselling author of If I Stay

An Excerpt fromAgain Again

1

A Love Story

This story takes place in a number of worlds.

But mostly in two.

It was the third day of Adelaide Buchwald’s summer job, the summer after her junior year at boarding school.

That summer she would fall in and out of love more than once,

in different ways

in different possible worlds.

In every world, she was consumed with the intense contradictions of her heart.

Adelaide wanted to be rescued and

she wanted independence.

She was inclined to laziness,

curiosity, and

magical thinking.

She was all charm and yet deeply miserable. She was a liar and she hated liars. She loved both truly and wrongheadedly. She appreciated beauty.

Her job was to walk five dogs, morning and night. They belonged to teachers who were on summer vacation.

EllaBella,

Lord Voldemort,

Rabbit,

Pretzel, and

the Great God Pan.

Those were the dogs. The morning she met Jack, Adelaide took them all to the dog run on the Alabaster Preparatory Academy campus. The run was a sandy space, fenced in and surrounded by trees. Looking through the leaves, she could see the spire of the Alabaster clock tower. She unleashed the dogs and sat…

1

A Love Story

This story takes place in a number of worlds.

But mostly in two.

It was the third day of Adelaide Buchwald’s summer job, the summer after her junior year at boarding school.

That summer she would fall in and out of love more than once,

in different ways

in different possible worlds.

In every world, she was consumed with the intense contradictions of her heart.

Adelaide wanted to be rescued and

she wanted independence.

She was inclined to laziness,

curiosity, and

magical thinking.

She was all charm and yet deeply miserable. She was a liar and she hated liars. She loved both truly and wrongheadedly. She appreciated beauty.

Her job was to walk five dogs, morning and night. They belonged to teachers who were on summer vacation.

EllaBella,

Lord Voldemort,

Rabbit,

Pretzel, and

the Great God Pan.

Those were the dogs. The morning she met Jack, Adelaide took them all to the dog run on the Alabaster Preparatory Academy campus. The run was a sandy space, fenced in and surrounded by trees. Looking through the leaves, she could see the spire of the Alabaster clock tower. She unleashed the dogs and sat on a bench while they frolicked. She listened to podcasts about stupid celebrities she didn’t even care about, trying to stop thinking about Mikey Double L.

Adelaide threw balls for the dogs. She threw sticks. She collected poop in small plastic bags, then threw them in the trash.

EllaBella said, You’re a gentle human. Can I lean on you? And Adelaide let the dog lean. She stroked EllaBella’s shaggy head.

She texted her mom about the breakup with Mikey. She had already told her dad the little she thought he needed to know.

Adelaide and her father, Levi Buchwald, had moved to Alabaster Prep for her junior year of high school. Adelaide lived in a dormitory, and Levi in Alabaster faculty housing. His new home was a small wooden house on the edge of campus. It was furnished with flea-market buys and overloaded with books. He was an English teacher.

Adelaide’s mother, Rebecca, and her little brother, Toby, had spent the year together in a rental house in Baltimore. Toby was very sick. Rebecca was taking care of him.

Rebecca was a knitter. She used to own a store called the Good Sheep Yarn Shop, where she taught classes. Much of her home was dedicated to wicker baskets overflowing with skeins of yarn. And plants, which she tended semi-obsessively. Rebecca was a person who focused very intently on the people, plants, and yarn in front of her.

She texted Adelaide back immediately about Mikey:

Oh blergh. I’m sorry. You okay?

Adelaide lied.

Yeah.

What happened?

The last thing Adelaide wanted to do was tell her mother the story of Mikey Double L.

…

…

Well, I’m here if you want to talk. Hug!

Rebecca often used the fat, spouting whale emoji. Adelaide had no idea what it was meant to symbolize. She wrote back.

Breakup was probably for the best anyway.

I was sad. But I slept it off and had eggs for breakfast, and now I’m feeling much better.

You’re very mature.

Adelaide was not at all mature. And the breakup wasn’t for the best. But she didn’t want her mother to spiral into anxiety. That was something Rebecca was inclined to do, with Adelaide off at boarding school. She wanted to hear that Adelaide ate well, stayed hydrated, got regular exercise, and slept enough.

When Rebecca spiraled into worry, the result was a series of phone calls filled with urgent requests for reassurance and connection that ended in Adelaide yelling at her mother, so Adelaide had devised a plan of regular texts giving evidence of those desirable behaviors.

“But I slept it off and had eggs for breakfast, and now I’m feeling much better” was what Rebecca needed to hear. Not

“I’m puffy and dehydrated from crying and

for breakfast I ate two Hershey bars and

truthfully I feel

unlovable

and ugly,

stupid

and broken.

I wish I could get a giant injection that would turn off my thoughts.

I would let a creepy doctor with a secret basement lab shoot a

random glowing substance into my ear if I knew it would stop me from feeling the way I do.

Last night, I tried binge-watching baking shows and then

I tried binge-watching zombie shows and then

I tried listening to happy music and

putting on a ton of makeup. So much makeup. Then my

eyebrows (with their makeup) looked scary and

their scariness made me depressed.

I was depressed by my own eyebrows.

I would have tried smoking cigarettes if I’d had any, and

I would have drunk Dad’s booze if he had any, but no luck on mind-altering substances, so

I passed out at three a.m. and when I woke up

I felt even worse and

my pillowcase was stained with lipstick.”

No. She couldn’t say that to her mother.

Adelaide just sent the text about the good breakfast and the night’s sleep. She added a zebra emoji for good measure, thinking Rebecca would like it. Then she put her phone in her pocket.

The Great God Pan lay on the ground, releasing gas.

EllaBella stayed close, pressing against Adelaide’s leg. I am thinking you have dog treats in your pocket, she said sweetly.

Lord Voldemort and Pretzel played chase. Rabbit growled at something on the other side of the fence.

And suddenly, a boy appeared. He was already in the run when Adelaide saw him, standing under a tree. He had a fluffy white dog on a leash.

Adelaide recognized the dog. It was B-Cake. B-Cake belonged to Sunny Kaspian-Lee.

A beat later, Adelaide recognized the boy as well, though she was sure she’d never seen him at Alabaster. He had a sweet V-shaped face and full lips. He was broad in the shoulders, with a narrow nose, smooth-shaven face, delicate ears. His light brown hair was wavy and a little wild. He was the sort of person you’d see immortalized in Roman statuary, his skin a warm Mediterranean olive, his chin and neck strong. He wore a light cotton jacket, a blue T-shirt, loose jeans, and green suede sneakers with blue stripes. The sleeves of the jacket were rolled up. His hands had the slight squashy look of leftover baby fat.

She knew him. She was certain of it.

He nodded at her, walked over, and draped himself onto the bench. There was something unusual going on with one of his legs. He walked with a roll of his left hip, and the fabric of his jeans flapped around that leg.

She remembered his walk.

The boy released the clip on the leash. B-Cake zoomed over to Rabbit and Rabbit exploded into the air with an anxious yip.

The boy laughed, covering his mouth with his fist. “Poor puppy,” he said.

“Hey, do I remember you?” she asked.

“Me? I don’t know.”

“I’m pretty sure I do remember you,” she said. “From Boston. Two years ago. We met at a rooftop party when I was in ninth grade.”

“A party on whose rooftop?”

“I don’t know. A friend of my friend. It was cold and you let me wear your scarf. Remember?”

The boy shook his head. “I have a radically terrible memory. Sorry.” Then he took out his phone. “ ’Scuse me, I’ve got to make a call.”

“Hey, do I remember you?” Adelaide asked.

“Me?” he said. “I don’t know.”

“I’m pretty sure I do remember you,” she said. “From Boston.”

“I’ve never been to Boston,” he said.

“Hey, do I remember you?” Adelaide asked.

“Me? I don’t know.”

“I’m pretty sure I do remember you,” she said. “I’m

pretty sure, in fact, that you took my number at a party two years ago and

you never, ever texted me, is what I’m

pretty sure of. I’m

pretty sure you’re the kind of terrible human being who says

Give me your number

when he doesn’t actually want the number, and I’m

pretty sure that’s not the kind of human being I need to talk to ever again,

especially not right now, when Mikey Double L is off to Puerto Rico full of virtue and

my entire sense of myself is

quite frankly

on the verge of liquidation.”

“Okay then,” he said. “I don’t need to make conversation.”

“I’m pretty sure I do remember you,” Adelaide said. “From Boston. Two years ago. We met at a rooftop party.”

“Really?”

“You were writing in a notebook,” she explained. “We started talking.”

“What was I writing?”

Adelaide flushed. She

wanted to tell the boy the answer, and also, she

didn’t want to tell him.

“We talked about dinosaurs, I think, and which ones we’d like to turn into.”

“Velociraptor, obviously,” said the boy.

“That’s what you said, but you’re one hundred percent wrong,” said Adelaide. “Pterodactyl.”

“Oh, you’re right,” he said. “Pterodactyl is better. Flight is always better.”

“I used to have a fear of plesiosaurs,” she told him. “Do you know about plesiosaurs? They were like, giant naked turtles with sea-monster necks.”

He laughed.

“At the rooftop party, you gave me your scarf,” continued Adelaide. “A red and black one. You said I could use it but to give it back, because it wasn’t even yours, it was your cousin’s.”

“Was I wearing a terrible leather jacket? Like a trying-too-hard jacket?”

“Yes.”

“Then it was me,” he said. “But I can’t remember.”

“My ride was leaving and I gave the scarf back to you, and you ripped a page from your notebook. You gave me the page and you had written me a poem:

Cerulean dress and

wide eyes, like a lion.

A raging wave of disobedient hair.

She contains

contradictions.”

“I wrote you a poem?”

“You did.”

Adelaide was sad he didn’t remember. Maybe he gave poems to a lot of girls. Or maybe he just couldn’t be expected to recall a party from two and a half years ago, when they would both have been only fourteen.

“I think poems, sometimes,” she told him. “Often, actually. But I rarely write them down.”

“Do you still have the one I wrote you?” he asked.

It was in her wallet. “Maybe somewhere,” she told him.

Adelaide had asked people if they knew a boy of his description, a boy with a roll of his hip, a poet, a boy with soft-looking wrists and golden skin and bitten nails. She had looked for him again and again as she sat in coffeehouses, as she waited in line for a burrito. At parties or ramen places, she looked for his sweet, full mouth. She was holding on to the chance that something good might happen.

To Adelaide, the boy was a promise. He promised her that

happiness could still exist,

could still be hers.

And that promise seemed even more important once the bad stuff started happening with Toby.

Then the Buchwald family left Boston. They moved to Baltimore for Toby’s treatment. Adelaide had accepted that she’d never see the boy in the leather jacket, ever again.

Now here he was.

He picked up a tennis ball that was lying in the sand. “Birthday! Come here, boy.”

“She’s a girl,” Adelaide said.

“Come here, girl.”

B-Cake ignored him.

“She doesn’t fetch,” Adelaide told him. “I know that dog.”

The boy laughed. “Okay. I don’t need to throw if she’s not into it.” He sat down.

“Did you hurt your leg?” Adelaide asked.

“No.” He didn’t speak for a moment. Then he said, “Actually, a plesiosaur bit me. I didn’t want to tell you because you seem to have a phobia.”

“Ha.” She chewed her lip. “Was that rude of me, asking?”

“A little.” He sighed. “I was born this way. It’s a skeletal limb abnormality.”

“I’m sorry. I asked without thinking.”

“You’re not entitled to the knowledge, is all. It’s my personal info. You know?”

“Okay.”

“Okay.”

“D’you want to ask me something intrusive now?” she said. “You can. I feel I owe you.”

“No thanks.”

“Ask me.”

“That’s all right.”

“Go on.”

“Fine. Ah, besides plesiosaurs, what scares you the most? Really, truly terrifies you?”

“My brother,” Adelaide said, the answer coming out before she had time to craft an amusing reply.

He picked up a tennis ball that was lying in the sand. “Birthday! Come here, boy.”

“She’s a girl,” Adelaide said.

“Come here, girl.”

B-Cake ignored him.

“She doesn’t fetch,” Adelaide told him. “I know that dog.”

The boy laughed. “Okay. I don’t need to throw if she’s not into it.” He sat down next to her. “I’m just taking her this weekend while the owner’s out of town. Are all of these yours?” He was talking about EllaBella, Rabbit, and the rest.

“I just walk them.”

He reached down to pet EllaBella, who was lying at Adelaide’s feet. “This dog is my favorite,” he said. “She has an excellent beard.” EllaBella was a bushy black mutt, nearly fifteen years old.

“She’s my favorite too,” Adelaide whispered. “But don’t tell the others.”

EllaBella was owned by Derrick Byrd, a single teacher of history. He’d come to Alabaster last year. He still had unpacked boxes in his house, which was two doors down from her dad’s.

“I never tell secrets,” said the boy. She liked the way his mouth moved when he spoke. He had blue paint underneath his nails.

“What did you paint?” she asked.

“I have access to the art studio for the summer. I’m painting abstract shapes, I guess you’d call them. Things that look like other things but aren’t those things.”

“Like what?”

“This one I’m doing--don’t laugh.”

“I won’t.”

“Well, you can laugh. It’s kind of a hippopotamus and it’s kind of a car. And also, it’s kind of a church. The meaning is what the viewer sees in it.”

“Hm.”

“I’m not getting the effect I want,” he said. “A lot of them look like blobs, not church hippos or whatever. It’s just the start of an idea.”

“What year are you?” she asked.

“Rising senior.”

“I’ve never seen you. On campus.”

He told her he had just transferred in. “My mother died six months ago.” She’d had leukemia. He and his father had just relocated from Spain. His dad used to teach at Alabaster and was now going to head the Modern Languages department.

“I’m so sorry,” Adelaide said. “About your mother.”

“Yeah, well. Thanks.” Lord Voldemort came up and wagged his stubby tail. “How come you walk so many dogs?”

“The teachers go away on summer travel. My father teaches English, but this summer he’s working in Admissions for extra money. I got the idea to collect people’s dogs and take them out, morning and evening. I feed them, too.”

“I’m gonna get Birthday to fetch,” he said. “Watch me.”

He chased after B-Cake, showing her the tennis ball. “You know you want it. Look at it, so yellow. Covered with awesome dog slime. Watch it, watch it!”