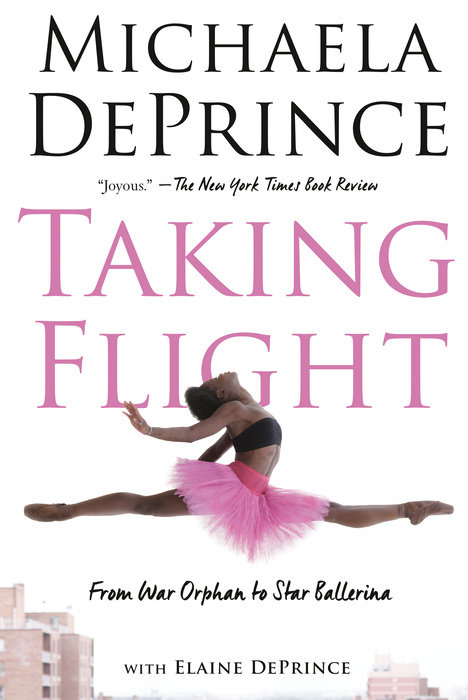

Taking Flight: From War Orphan to Star Ballerina

The extraordinary memoir of an orphan who danced her way from war-torn Sierra Leone to ballet stardom, most recently appearing in Beyonce’s Lemonade and as a principal in a major American dance company.

"Michaela is nothing short of a miracle, born to be a ballerina. For every young brown, yellow, and purple dancer, she is an inspiration!” —Misty Copeland, world-renowned ballet dancer

Michaela DePrince was known as girl Number 27 at the orphanage, where she was abandoned at a young age and tormented as a “devil child” for a skin condition that makes her skin appear spotted. But it was at the orphanage that Michaela would find a picture of a beautiful ballerina en pointe that would help change the course of her life.

At the age of four, Michaela was adopted by an American family, who encouraged her love of dancing and enrolled her in classes. She went on to study at the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School at the American Ballet Theatre and is now the youngest principal dancer with the Dance Theatre of Harlem. She has appeared in the ballet documentary First Position, as well as on Dancing with the Stars, Good Morning America, and Nightline.

In this engaging, moving, and unforgettable memoir, Michaela shares her dramatic journey from an orphan in West Africa to becoming one of ballet’s most exciting rising stars.

“Michaela DePrince is the embodiment of what it means to fight for your dream.” —Today

“Michaela DePrince is a role model for girls on and off stage.” —NYLON

An Excerpt fromTaking Flight: From War Orphan to Star Ballerina

Before I was the “vile” and “chilly” Odile, I was Michaela DePrince, and before I was Michaela, I was Mabinty Bangura, and this is the story of my flight from war orphan to ballerina.

In Africa my papa loved the dusty, dry winds of the Harmattan, which blew down from the Sahara Desert every December or January. “Ah, the Harmattan has brought us good fortune again!” he would exclaim when he returned from harvesting rice. I would smile when he said that because I knew that his next words would be “But not as good a fortune as the year when it brought us Mabinty . . . no, never as good as that!”

My parents said that I was born with a sharp cry and a personality as prickly as an African hedgehog. Even worse, I was a girl child--and a spotted one at that, because I was born with a skin condition called vitiligo, which caused me to look like a baby leopard. Nevertheless, my parents celebrated my arrival with joy.

When my father proclaimed that my birth was the high point of his life, his older brother, Abdullah, shook his head and declared, “It is an unfortunate Harmattan that brings a girl child . . . a worthless, spotted girl child, one who will not even bring you a good bride-price.” My mother told me that my father laughed at his brother. He and Uncle Abdullah did not see eye to eye on almost anything.

My uncle was right in one respect: in a typical household in the Kenema District of southeastern Sierra Leone, West Africa, my birth would not have been cause for celebration. But our household was not typical. First of all, my parents’ marriage had not been arranged. They had married for love, and my father refused to take a second wife, even after several years of marriage, when it appeared that I would be their only child. Secondly, both of my parents could read, and my father believed that his daughter should learn to read as well.

“If my brother is right and no one will wish to marry a girl with skin like the leopard, it is important that our daughter go to school. Let’s prepare her for that day,” my father told my mother. So he began to teach me the abjad, the Arabic alphabet, when I was just a tiny pikin, barely able to toddle about.

“Fool!” Uncle Abdullah sputtered when he saw Papa molding my little fingers around a stick of charcoal. “Why are you teaching a girl child? She will think that she is above her station. All she needs to learn is how to cook, clean, sew, and care for children.”

My spots scared the other children in our village. Nobody would play with me, except my cousins on occasion, so I would often sit alone on the stoop of our hut, thinking. I wondered why my father worked so hard panning for diamonds in the alluvial mines, diamonds that he would not be allowed to keep. It was hard, backbreaking work to stand bent over all day. Papa would hobble home at night, because his back, ankles, and feet ached. His hands would be swollen and painful from sifting the heavy, wet soil through his sieve. Then, one night while Mama was rubbing shea butter mixed with hot pepper into Papa’s swollen joints, I overheard a conversation between them, and understood.

“It is important that our daughter go to school to learn more than we are capable of teaching her. I want her to go to a good school.”

“If we are frugal, the money from the mines will eventually be enough to pay her school fees, Alhaji,” my mother said.

“Ah, Jemi, count the money. How much have we saved so far?” Papa asked.

Mama laughed. “This much, plus the amount I counted the last time you asked,” she said, holding up the coins he had brought home that evening.

I smiled a secret smile from my small space behind the curtain. I loved to listen to my parents’ voices at night. Though I cannot say the same for the voices of Uncle Abdullah and his wives.

Our house was set to the right of my uncle’s house. Uncle Abdullah had three wives and fourteen children. Much to his unhappiness, thirteen of his children were girls, leaving my uncle and his precious son, Usman, the child of his first wife, as the only males in the household.

Many nights I would hear cries and shouts of anger drifting across the yard. The sounds of Uncle Abdullah beating his wives and daughters filled my family with sadness. I doubted that Uncle Abdullah ever loved any of his wives, or he would not have beaten them. He certainly didn’t love his many daughters. He blamed any and all of his misfortunes on their existence.

My uncle cared only about his one son. He called Usman his treasure and fed him delicious tidbits of meat while his daughters looked on, hungry and bloated from a starchy diet of rice and cassava, that long, brown-skinned root vegetable that lacks vitamins and minerals. And nothing was more galling to my uncle than finding me outside, sitting cross-legged on a grass mat, studying and writing my letters, which I copied from the Qur’an. He could not resist poking me with the toe of his sandal and ordering me to get about the duties of a woman.

“Fool!” Uncle Abdullah would sputter at my papa. “Put this child to work.”

“What need does she have of womanly chores? She is only a child herself,” Papa would remind his brother, and then couldn’t resist adding: “Yes, not even four years old, and yet she speaks Mende, Temne, Limba, Krio, and Arabic. She picks up languages from the marketplace and learns quickly. She will surely become a scholar.” Papa didn’t need to rub any more salt in Uncle Abdullah’s wounds by reminding him that Usman, who was several years older than me, lagged far behind me in his studies.

“What she needs is a good beating,” Uncle Abdullah would counter. “And that wife of yours, she too needs an occasional beating. You are spoiling your women, Alhaji. No good will ever come of that.”

Perhaps Papa should not have bragged about my learning. The villagers and my uncle thought that I was strange enough with my spots, and my reading made me even stranger in their eyes and made my uncle hate me.

The only thing that my father and his brother had in common was the land that fed us, sheltered us, and provided the rice, palm wine, and shea butter that we sold at the market.

At night, when I heard the cries coming from across the yard, I’d turn my ear toward my parents resting on the other side of the curtain. From there I heard sweet words of love and soft laughter. Then I would thank Allah because I had been born into the house on the right, rather than the one on the left.