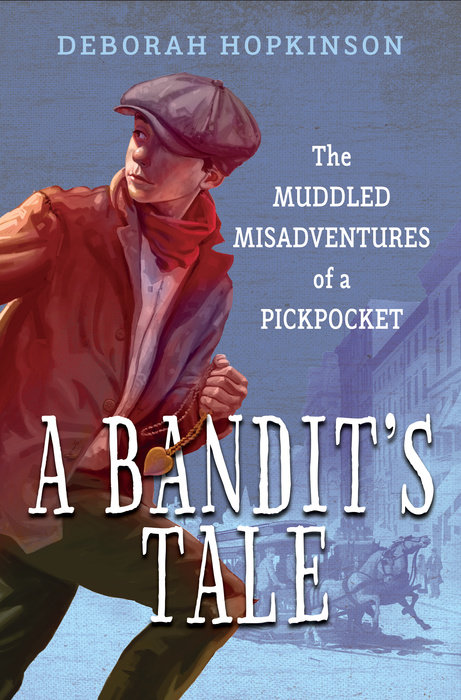

A Bandit's Tale: The Muddled Misadventures of a Pickpocket

Author Deborah Hopkinson

A Bandit's Tale: The Muddled Misadventures of a Pickpocket

From an award-winning author of historical fiction comes a story of survival, crime, adventure, and horses in the streets of 19th century New York City.

Eleven-year-old Rocco is an Italian immigrant who finds himself alone in New York City after he's sold to a padrone by his poverty-stricken parents. While working as a street musician, he meets the boys of the infamous Bandits' Roost, who teach him the art of pickpocketing. Rocco embraces his new life of crime—he's good at it, and it's more lucrative than banging a triangle on the street corner. But when he meets Meddlin' Mary, a strong-hearted Irish girl who's determined to help the horses of New York City, things begin to change. Rocco begins to reexamine his life—and take his future into his own hands.

An Excerpt fromA Bandit's Tale: The Muddled Misadventures of a Pickpocket

Chapter 1

In which my (mis)adventures begin

and many tearful goodbyes are said

These days, when anyone asks, I say I'm an American, New York City-born. And why not? Because, in a way, I was born here.

Right here, smack in the middle of this giant, swarming bees' nest of a place, is where I became me: Rocco Zaccaro, pickpocket, liar extraordinaire, and escaped convict, among other things. I'm a true guttersnipe--a scruffy and badly behaved street kid. I'm an alley rat of Mulberry Bend and Bandits' Roost.

And though it may not be exactly correct to say I was born in New York City, well, I ask you: Just what is truth? My adventures have taught me that truth isn't a solid thing, like a brick you can heft in your hand. Naw, it's more like a shadow that changes shape depending on the time of day. Your shadow looks one way in the morning, another in late afternoon. At noon on a sunny day? It just about disappears. But it's still your shadow.

Nonetheless, I'm guessing you do…

Chapter 1

In which my (mis)adventures begin

and many tearful goodbyes are said

These days, when anyone asks, I say I'm an American, New York City-born. And why not? Because, in a way, I was born here.

Right here, smack in the middle of this giant, swarming bees' nest of a place, is where I became me: Rocco Zaccaro, pickpocket, liar extraordinaire, and escaped convict, among other things. I'm a true guttersnipe--a scruffy and badly behaved street kid. I'm an alley rat of Mulberry Bend and Bandits' Roost.

And though it may not be exactly correct to say I was born in New York City, well, I ask you: Just what is truth? My adventures have taught me that truth isn't a solid thing, like a brick you can heft in your hand. Naw, it's more like a shadow that changes shape depending on the time of day. Your shadow looks one way in the morning, another in late afternoon. At noon on a sunny day? It just about disappears. But it's still your shadow.

Nonetheless, I'm guessing you do want to know some facts--basic, hard facts--so you can make up your mind about me. Am I a poor, misfortunate victim, whose parents sold him to a wicked villain? Or am I a young scoundrel, who deserves every bad turn that has come his way? Well, as I said at the beginning, you'll have to decide that for yourself. All I ask is that you keep an open mind.

As for those facts, I arrived in New York City in March 1887 at the age of eleven, plucked from the region in southern Italy we call Basilicata, province of Potenza, hill town of Calvello, a desperately poor place, where peasants like my parents struggled to survive.

It's also a fact that Mama named me Rocco because I was born on August 16, feast day of Saint Rocco, patron saint of the sick, dogs, and falsely accused people.

Mama said that Rocco was a rich man from Montpellier, France, who gave up his fortune to go on pilgrimage. While caring for others during an epidemic, Rocco fell ill. He was exiled to the forest, where a dog--and the dog's noble owner--befriended him and nursed him back to health. But when Rocco finally returned home, he was falsely accused of being a spy and put in jail, where he stayed for five years, until he died. Whew! Quite a story, don't you think?

Mama told me that statues of Rocco often show him with a dog. I've never had a dog myself. However, as you will discover later in this history, I have met a man who, like the saint himself, was befriended by a kindly canine. As for Saint Rocco being the patron of the falsely accused, well, I'll have more to say about that later too.

Calvello is like no place you'll find in America. Our village is perched on the side of a steep, jutting hill, which actually looks a bit like a molehill sticking up from the pastures and fields below. As for the town itself, it's no more than a jumble of limestone dwellings, all huddled next to one another like pigeons in a storm.

Each May, families would celebrate the festival of the Madonna del Monte Saraceno, honoring the Virgin Mary with songs and a procession that wound through the streets.

Come fall, we'd trail Mama like little chicks as we combed the forest for chestnuts: le castagne. Anna and Emilia and I would kick the leaves away, searching for the fallen treasure hidden beneath, with little Vito toddling behind us on his chubby legs. Chestnuts have spiky burrs, and it took days to pick them out of our skin. We didn't mind--the taste of roasted chestnuts was worth it.

But everyday life was hard. Children in Calvello didn't go to school beyond age eight or nine. We were needed to help our parents. Sometimes, when we were supposed to be asleep, I'd hear Mama and Papa talking anxiously, their voices sharp as those stinging prickles. They worried about paying rent in the form of grain to Signor Ferri. Mama fretted about having enough food to get through the winter.

We kept a goat, plus a few sheep and pigs. We tried to slaughter at least one pig each winter so Mama could make sausages. She spiced them with wild fennel and hung them from the rafters to dry.

We'd had our own donkey once, but poor crops and high taxes had forced Papa to sell it. Now Signor Ferri owned the only donkeys and mules in town, renting them out to Papa and the other peasants when there was a need to carry heavy loads. At ten, in addition to helping in the fields, I'd gotten an extra job working in the landlord's stable--the very job I'd lost in that public, shameful way.

All in all, our family's prospects were bleak when the stranger Giovanni Ancarola appeared in our midst, spinning a story bright as gold. Even if I hadn't embarrassed Papa, his proposition would have been hard for my parents to pass up. Signor Ancarola was a padrone--a boss man and patron--who held out a promise, a chance for things to be different someday.

Best of all, the padrone offered cash. Under the contract, Signor Ancarola would get me, a string bean of a boy (and a disgrace besides), and be my master. My parents would receive an amount equal to twenty American dollars each year for the next four years, so long as I kept working for him in America. Not only that, but there'd be one less mouth to feed with me gone.

Two days from that fateful night, Giovanni Ancarola returned to take me away. To my astonishment, he had Old Biter with him.

"Where'd you get that donkey?" I blurted out.

"Like him, do you?" Signor Ancarola grinned. "Signor Ferri sold him to me. He said you were good with donkeys, and you'd especially know how to handle this one."

I swallowed hard and felt my heart race with anger. That's when I realized how the padrone had chosen me: The landlord had sent him to our door. Signor Ferri wanted me gone from his village.

And I knew exactly why.

Signor Ancarola went inside to finish his business with Papa, leaving me holding Old Biter's rope. Six-year-old Emilia tried to hug me one more time, without getting too close to the donkey. Tears ran down her cheeks.

But Anna, the oldest of us at thirteen, and the boldest too, peered at me with dry eyes. Anna wouldn't have been frightened the way I was; she wouldn't have tossed and turned all night, imagining gigantic waves swallowing her on the passage.

Anna grasped my free hand with both of hers, pressing a pair of knit socks into it. She was clever, good at knitting, at cooking, at everything she did. Leaning forward, she whispered urgently, "Come back for us someday, Rocco. Come back for me."

I nodded, but that wasn't good enough for her. Anna squeezed my hand so hard it hurt. "You must promise. Will you do that, little brother?"

"Sì, I promise," I croaked.

Papa and the padrone emerged into the sunshine. The padrone took the donkey's rope from me and said, "Time to go, Rocco. You will do fine--if you listen and follow the rules."

He started off, leaving my family huddled in our doorway. I began to follow, then Vito started wailing, "Rocco, Rocco!"

I ran back and hugged Anna and Emilia. Even Anna was crying now. I swept up little Vito, who wrapped himself, spider-like, around my neck. He was only two, and as I tickled his warm belly, I wondered if he would even remember me.

Mama folded me in her thin, strong arms. "I'll pray to the saints for you. Saint Rocco will keep you well." That was always her biggest fear: that we would get sick.

I gave Papa a quick hug. He kept his face a mask. I almost whispered the truth then, all of it. But I swallowed the words. I had made a promise. Besides, it was too late.

I looked back once before we turned the corner, half hoping Papa would change his mind and call me back. He was patting his pocket, probably already thinking about the money. If he had other feelings, they were buried much deeper than a pocket.

A few streets away, we stopped to pick up two other boys. They were pathetic-looking creatures, ten-year-old cousins who didn't seem strong enough to walk to Naples, more than a hundred miles away, let alone embark on a perilous boat trip across a stormy ocean.

I didn't know them well. Their mothers were twins, which might be why I had trouble telling them apart at first. They had shaggy black hair and dark round eyes. Marco was slight, Luigi slender as a reed.

"Call me Padrone. If anyone asks, I'm your uncle," Padrone told us. He would repeat this instruction many times.

"You don't look like us," I murmured under my breath, though I knew it was a mistake as soon as it was out.

Ever since I can remember, Mama had warned me about speaking without thinking first. "Your words shouldn't rush out of you like a hasty stream," she would say. "You must try to be more like Papa."

I understood what she meant; I just had a hard time doing it. Often, as soon as a thought dropped into my head, it popped out of my mouth.

Padrone did not appreciate my comment. He gave me a quick cuff on the side of my head. "When I give you orders, you don't talk back. That goes for all of you. Understand?"

"Sì, sì, signore," we all chimed in unison.

"Here, Rocco," said Signor Ancarola, tossing the donkey's rope to me. "Take charge of your friend."

And so we set out.

Chapter 2

Giving an account of a dusty journey by foot;

another goodbye

Marco and Luigi wouldn't stop crying. It was plain to see they'd never left home before. Their parents must have been desperate, because the two had the look of chicks pushed out of the nest too soon. Snot dripped from their noses. Rivulets of grimy tears stained their cheeks.

In short, it was disgusting.

"Wipe your noses," I hissed as we snaked down to the valley floor. "Stay behind the donkey and stop sniveling. No one wants to hear you."

Without a word of protest, they did exactly as I ordered, falling silently into place behind Old Biter like pocket-sized soldiers heading off to war. I was glad. If they'd kept up their whimpering and sniffling, I was afraid I might start too. Their tears reminded me that every mile took me away from the only home I had.

Still, even on that first, bewildering day, as each twist and turn of a dusty mule path brought the sight of something new, I couldn't help feeling a tiny shiver of excitement. I was off on an adventure, even if I was leading a bad-tempered donkey. Who could tell what might happen next?

Now, you might think that even a donkey might also be a little excited, in a donkeyish sort of way, about being on a journey and seeing new things. Well, you would be wrong. In fact, it was as if Old Biter blamed me that he was plodding along a dusty road instead of munching hay contentedly at home.

The night before we'd set off, while I'd tossed and turned with fear about what lay ahead, I'd fingered the scar on my arm. The only good thing about being sent away, I'd decided, was that I'd never have to look at Old Biter's ugly yellow teeth or feel them tear into my flesh again.

And here he was--teeth and all. That spiteful creature lit into me as soon as Padrone called a halt to our first day's walk. I'd begun to unload the bags from his back when he whipped his neck around. In the blink of an eye, he went for my left arm, no doubt hoping to add another half-moon scar to the one he'd already given me.

I should have been more careful, I suppose. I should have talked to him gently and moved more slowly. I was just so tired, inside and out. My feet were sore. My heart was sore. Luckily, I was able to jump back in time to get just a nip, not a bite. I yelped and stamped my feet. I almost kicked him, then thought better of it. Old Biter would definitely kick back.

"I thought you were supposed to know about this beast," said Padrone. "I hope the skin isn't broken. I can't afford for you to get sick from a wound.

"Leave the old boy to me," he added, taking the rope from my hand. "Go collect firewood."

It occurred to me that Giovanni Ancarola might be as vicious as my ill-tempered four-legged friend, but he wouldn't trample us entirely. Marco, Luigi, and I were, after all, valuable property.

Our journey soon settled into a pattern. We followed rugged shepherds' paths and well-worn mule tracks, winding our way up and down hills, through villages, and onto the main road to Naples. Padrone had warned that it might take us at least a week, and that we had no time to lose.

"We will walk all night if we have to," he told us. "We cannot be late."

Luigi and Marco continued to sob themselves to sleep each night, though where they got the energy, I have no idea. Still, they walked--I'll say that for them. We all did, from early light until it was too dark to see. We carried bread, cheese, and water and ate outside, sitting on the ground. On occasion our padrone would plant us outside of a little tavern so he could drink some wine. There was no danger of us running away. Where would we go in a strange town with no friends or family?

Padrone pushed us. It couldn't have been easy with his limp, but he never slowed down. He never mentioned his leg or why it dragged. Whatever else he was, Signor Ancarola wasn't a complainer. Perhaps that was why he couldn't stand grumbling in others. We learned to hold our tongues no matter how hungry or thirsty we were, or how big the ugly blisters blossoming on our feet became.

"Come on, the ship will not wait," Padrone would bark at Luigi whenever he began to lag behind, which was often. Luigi seemed to live in a world of his own, a dreamy place where he might stop for a minute to stare up at a cloud, mouth open, or bend down to count ants in the dirt. Sometimes I wondered if he truly grasped what was happening to him or where we were heading.