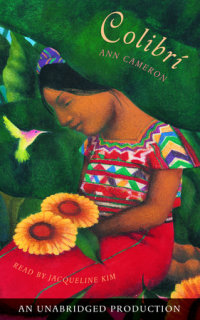

Colibri

When Tzunún was little, her mother nicknamed her Colibrí, Spanish for “hummingbird.” At age four, Colibrí is kidnapped from her parents in Guatemala City and ever since she’s traveled with Uncle, the ex-soldier and wandering beggar, who renamed her Rosa. Uncle told Rosa that he looked for her parents, but never found them.

An Excerpt fromColibri

1The ValleyMoss and bright grasses glistened around the spring. The earth smelled as if it were singing.I scooped up water in my hands and drank.We ate our last pieces of dry bread. I shook the crumbs out of my shawl, folded it into a square, and put it on my head to shade my eyes."Let's go, Rosa," Uncle said.He always called me Rosa. My real name, Tzunœn, was a secret I had almost forgotten.The road was narrow. We walked on, Uncle carrying our belongings on his back in the black suitcase with the broken zipper. So nothing would fall out, he'd stuffed the suitcase inside a rope bag with a carrying strap. The leather strap went around his forehead and left a mark there.We were in the Ixil Valley, in the high mountains of Guatemala where it rains a lot and sometimes there's frost in the winter. Beside us was a forest of tall pines with flowers in the sunlit spaces--tiny star-shaped red ones, shaggy purple ones with rough raggedy leaves, and seven-foot-tall yellow daisies. The daisies were my favorite, the way they bent their heads and seemed to smile at me.There were rocks all around, too--enormous boulders that had tumbled down the mountains in ancient times and got to flatter land and just hit a place where they stuck.Pinecone seeds sprouted on top of boulders, driving their roots into the rock. They'd cracked some boulders wide open.The seeds in pinecones are lighter than a grain of sand. Sometimes I'd held them in my hand and blown them away, as if they were fine grains of dust. Yet they had the power deep inside them to split rock. Power silent and invisible, but real as the mountains. What was it? Where did it come from?I wanted to ask Uncle, but I didn't. He disliked questions. Sometimes for whole days he hardly talked.Uncle said he was a ladino. That is, he claimed he had some Spanish ancestors way back, as well as Mayan ones--and he said that made him moody and gave him a blood disease. He said his Spanish blood hated his Mayan blood, and his Mayan blood hated his Spanish blood, and they were together in him fighting all the time.I didn't see how that could be. Blood is blood.We walked along by pastures where sheep were grazing--white ones and black ones, grown ones and little lambs just learning to walk. I thought they were sweet, but I kept that to myself. Uncle called the people he didn't like--which was most people--"stinking sheep." I figured that meant he didn't like sheep.Behind us a pickup tore up the road, the grinding of its motor eating the stillness of the forest. We moved out of the way and it rocked along beside us, drowning the smell of grass and pines in smoke. The driver glanced at us, slowing down to see if we wanted a ride. A lot of passengers were already in the back, holding on tight to an iron frame welded to the pickup bed, but there would have been room for us.Uncle waved the driver on.That was one of the hard parts of being with Uncle. I could never tell what he would do. Often he would accept a ride, and at the end, when the driver was collecting money from everybody, he would try to sneak away without paying. Other times, even if he had money, he'd turn a ride down and just keep walking as if he could walk to the end of the world.He was a fast walker. When I was little and couldn't keep up, he used to get mad and say he would give me away.My sandals were tight and hurt my feet. I was growing fast. Too fast, Uncle said.I didn't know exactly how old I was, because I had lost track. Uncle figured I was twelve.We kept walking, and pretty soon we were standing on a ridge, looking down into a valley where a town was spread out like the flat bottom of a bowl. We could see tile and tin roofs of houses, and a big white church in the center of town."Nebaj," Uncle said. It was a place I'd never heard of. He hadn't told me where we were going.Uncle got out his machete and hacked down a sapling at the side of the road. He trimmed it into a walking stick.We started the descent to Nebaj, Uncle striding along, swinging the stick. The town had looked close, but the road down was long and winding. We got to a scattering of houses, and the dirt road fixed itself up fancy, just as a person would going to town. It became a street of smooth paving stones, lined with low houses painted in yellows and reds and blues.The sun was low in the west, and the day was getting cool. We stood in the dark shadow of the houses. I took my shawl off my head and wrapped it around me. Uncle held out his walking stick, and I took hold of one end of it. I had to.He was starting in on being blind.I didn't mind so much when he got to a town and turned lame, or deaf and dumb. When he turned blind, that was the worst. He wouldn't tell me which way to go. But if I went the wrong way, he would get mad and poke at me with the stick."To the church," he said.I guessed which way it was and walked ahead of him. Uncle followed, holding the other end of his walking stick, his chin raised high and a dead look in his eyes.One day, we were in a town where I saw a girl helping her father, who was really blind, but you could hardly tell it.