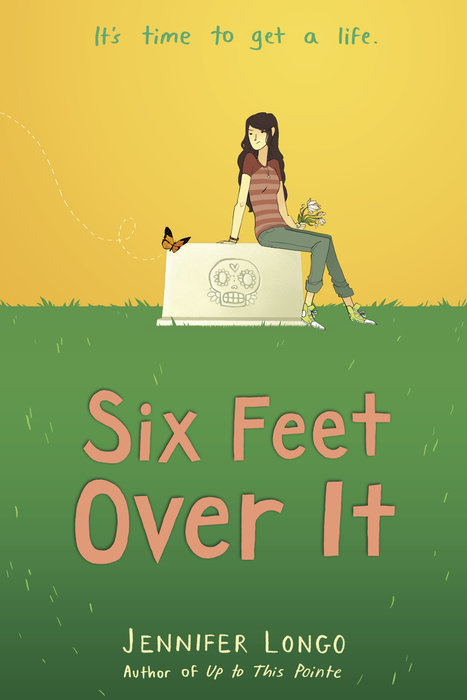

Six Feet Over It

Author Jennifer Longo

Six Feet Over It

A darkly humorous and heart-wrenchingly beautiful young adult novel about a girl surrounded by death that will change the way you look at friendship, love, and life.

“Like nothing you’ve read before.” —Bustle Online

No one is more surprised than Leigh when her father buys a graveyard. Less shocking is the fact that he’s too lazy to look farther than the dinner table for employees. Working the literal graveyard shift, she …

A darkly humorous and heart-wrenchingly beautiful young adult novel about a girl surrounded by death that will change the way you look at friendship, love, and life.

“Like nothing you’ve read before.” —Bustle Online

No one is more surprised than Leigh when her father buys a graveyard. Less shocking is the fact that he’s too lazy to look farther than the dinner table for employees. Working the literal graveyard shift, she becomes great at predicting headstone choice (mostly granite) and taking notes with one hand while offering Kleenex with the other.

Sarcastic and smart, Leigh should be able to quit this stupid after-school job. But her world’s been turned upside down by the sudden loss of her best friend and the appearance of Dario, the slightly-too-old-for-her gravedigger. Can Leigh move on, if moving on means it’s time to get a life?

“Darkly funny and deeply moving. An original, memorable voice.” —Jennifer L. Holm, New York Times bestselling author

“A wildly funny coming-of-age story about life, love, death, and everything in between.” —Sarah McCarry, author of All Our Pretty Songs

An Excerpt fromSix Feet Over It

One

I was born dead. Or died shortly after--Meredith’s story changes depending on her audience and her mood. “The first thing Leigh did after she was born was die!” she loves bragging to people, working her well-worn “tragedy + more tragedy = comedy” routine. And yes, I was born nearly three months early--a two-and-a-half-pound “micro preemie”--but I have since learned from watching medical dramas that premature babies flatline all the time, and these days reviving them is really no big whoop. Wade says it’s just bravado masking Meredith’s injured maternal pride over how I subsequently lived--thrived--without the protection of her womb, but most parents wouldn’t drag that chestnut out for laughs. Makes me cringe.

“Oh, Leigh,” she and Wade constantly moan. “Don’t be so dramatic, my God!”

If my eyes so much as mist up, get a little dewy over anything--epic Wade and Meredith eye rolling. Sighs are heaved. A person lucky enough to be brought back from a birth/death and go on to enjoy freakishly perfect health has nothing to cry about.

They buy graveyards on the sly…

One

I was born dead. Or died shortly after--Meredith’s story changes depending on her audience and her mood. “The first thing Leigh did after she was born was die!” she loves bragging to people, working her well-worn “tragedy + more tragedy = comedy” routine. And yes, I was born nearly three months early--a two-and-a-half-pound “micro preemie”--but I have since learned from watching medical dramas that premature babies flatline all the time, and these days reviving them is really no big whoop. Wade says it’s just bravado masking Meredith’s injured maternal pride over how I subsequently lived--thrived--without the protection of her womb, but most parents wouldn’t drag that chestnut out for laughs. Makes me cringe.

“Oh, Leigh,” she and Wade constantly moan. “Don’t be so dramatic, my God!”

If my eyes so much as mist up, get a little dewy over anything--epic Wade and Meredith eye rolling. Sighs are heaved. A person lucky enough to be brought back from a birth/death and go on to enjoy freakishly perfect health has nothing to cry about.

They buy graveyards on the sly and perform stand‑up comedy routines about their kid’s near death and I’m dramatic?

I don’t remember when I started calling them Wade and Meredith.

So here we are. I am. Non-selling days I walk home as fast as I can from school, step on every crack I see. No, living here is not technically Meredith’s fault; Wade bought the graveyard without even telling her, saw a classified ad--Graveyard for Sale--and signed mortgage papers she never even saw. But still--come on.

I keep my eyes down all the way to Sierrawood, through our out-of-control Gothic black wrought-iron entrance gates, yet another genius Wade idea. They’re just stupid. Every single time I look at them, I think, “Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again . . .” and I’m in a Daphne du Maurier novel, alone behind the gates of a creepy estate coincidentally also presided over by a ridiculous man. Huh.

Just inside the Manderley gates, ducks paddle in a pond, beside which is a wooden sign, small and low to the ground, that reads: THIS IS A NON-ENDOWMENT CARE FACILITY. Non-endowment, according to Wade, means the families don’t pay extra into funds to maintain the graves; therefore everyone should be grateful he even gases up the mower and runs it at all. A little farther past the pond, another very small, carefully hand-printed sign reads: ALL FLOWERS, ARTIFICIAL AND REAL, WILL BE REMOVED ON TUESDAYS TO FACILITATE MOWING. Which everyone knows is a big joke--people are figuring out pretty quickly that most of the signage around Sierrawood, like Wade himself, is all talk, no action. GATES CLOSED AT DUSK? If we remember. NO MUSIC ALLOWED? Tell that to Mrs. Irvin, who hauls a boom box over to J 72 in Peaceful Glen so she can blast the sound track of the Broadway show Carousel for her sister week after week. Even with Wade’s mower running and my headphones on, every Wednesday I can hear Shirley Jones hollering about having “a real nice clambake.”

With all my attention concentrated on the gravel road beneath my feet, I pretend the graves away. Most of the headstones are flat, so if I squint it’s just a house, just a nice house near a nice park, just a park. But on digging days the pretense dissolves as I run to the house, my heavy backpack beating me senseless, away from the backhoe and the pile of soil beside it, Jimmy the contracted grave digger leaning casually on his shovel.

Today is an office day, Wednesday, so I do not run. I trudge from school, moving especially slowly so that I miss Real Nice Clambake. She honks and waves on her way out as we pass through the Manderleys. In the office, I toss my backpack beneath the desk and shove the dusty stack of back issues of Mortuary Monthly magazine to the floor. (Why do we continue to get this thing? We’re not a mortuary! I’ve called them twice to cancel already.) This stupid brown cave. Tiny building beside the pond, the hills of graves rising all around it. There are windows on every wall, large and well positioned for crow’s-nest-type spying, but the dark wood paneling, matted brown shag rug, and black vinyl wingback chairs seem to suck the light right out. Like the clientele aren’t depressed enough. The shag and walls are gummy with residual pipe smoke from the previous owner, who sat in here puffing for fifty-three years before selling Sierrawood to Wade and packing his pipe off to Maui. Who in the world who isn’t a British detective smokes a pipe? People who own graveyards, apparently. I bet he wore a monocle, too. The smell makes my head hurt.

I prop the door open and heave the ginormous English lit book we’ve been assigned onto the funeral-scheduling desk calendar.

The heartsick Ceres seeks her daughter / She searches every land, all waves and waters.

Okay. Here’s the thing about Ovid, about Metamorphoses: I do get it--Troy falls, Rome rises. The universal principle, nothing is permanent, everything changes, anything, anyone you may have to hold on to, take comfort or care from, will leave. Die. Which is awesome. But then really, Ovid? You need fifteen books of narrative poetry to present this worn-out thesis? That I don’t get. Beauty for beauty’s sake, Mrs. McKinstry says, and we’re not reading all fifteen books, just the greatest hits, so count your blessings. Keep reading. She keeps quizzing.

Through the open windows I hear the sound of tires on the drive. My hands go damp--Not today, just let me sit here with Ovid, please oh please--and thank God it’s not a customer, just the flower van. Rivendell Nursery. They seem to be Sierrawood’s number one provider of beauty-queen-contestant-sashed wreaths. Mother. In Memoriam. Miss Sierrawood Hills. A lady brings them, and she also does weekly and monthly bouquets for out-of-town relatives and infirm or lazy local family members. Birthdays, holidays. Paying a stranger to visit your dearly departed seems sort of beside the point, but whatever.

The van passes the pond, and halfway up Poppy Hill the lady hops out wearing denim overalls; her hair is tied in a knot on top of her head and she lugs heavy baskets of uninspired calla lilies across the grass. But then someone else climbs out the back of the van.

Emily.

My only friend, left behind at the ocean. Months since I’ve seen her and I thought she was gone forever, but now here she is.

Emily?

No. My brain loves to turn every small, dark-haired girl I see into Emily, but no. This girl is maybe a little taller, and she’s out there wearing a dress--a dress, for crying out loud--and tall black boots. She runs to help with the lilies. She heaves armloads of arrangements and potted plants, refers to a list, searches for headstones, places blossoms and baskets. That dress is going to get filthy.

Just some girl.

Not Emily.

I salt the wound, pick up the phone receiver. Dial Emily’s Mendocino house.

The number you have reached . . .

Same as the last hundred times I tried. Why do I do it to myself?

Back to Ovid.

Chill October air moves through the window and around the open door, swings the dust and stale pipe residue around my head full of Ceres searching for her daughter and a sound track of ducks quacking beneath the willows.

“Hello?”

I slam my hand into hardback Ovid, startled. In the doorway, Dress and Boots Girl winces.

“Oh God, sorry! Sorry!”

I rub my red knuckles and she steps in.

“Are you okay? Can I . . .”

“No, it’s fine, it’s . . . okay.” I squeeze my pink fingers, push Ovid aside.

Not Emily. Younger than me. Small. The knots of her dark hair are braided, wound and pinned above each ear. Her dress is cotton, pale blue stripes, and she has a white soil-stained apron tied around her waist. The black boots are leather, tall as her knobby knees. She should be herding Alpine goats. Instead, she’s just standing here smiling, shifting her weight. Maybe she has to pee.

“Can I help you with something?”

She turns her head sideways, reads the Metamorphoses spine.

“Are you reading that?”

I shrug.

“For fun?”

“School.”

She nods. “What do you think?”

“Um.” Why does she care? “Kind of depressing.”

“Sure.”

“And wordy.”

She smiles. “Yeah.”

“And he doesn’t seem to think much of the ladies.”

She leans against the desk. “How so?”

Uh. Okay, Mrs. McKinstry. I guess we’re doing this.

“Well,” I say, “he’s no fan of subtlety. His women are wallowing in grief and then--oh, look out, literal metamorphosis!--all of a sudden they’re mute. Or petrified, or turned into gold. Or a cow.”

She laughs. “You’re so right.”

Her laugh is not Emily’s, not bright and big. This girl’s is . . . lighter? Smaller.

“Okay,” she says, “but don’t you love the comfort of it?”

Clearly she has read it for fun. “The what?”

“Well, I mean the whole thing that it’s always been this way, it always will be, nothing is static, life is cyclical, no one ever really leaves. . . . It’s very . . . I don’t know. I love it.”

“Guess I’m not to the comfort part yet. People are still just . . .”

“Dying,” she says. “Yeah.”

She goes back to smiling.

“So,” I say again, “is there something I can--”

“Oh! Sorry, yes . . .” She hands me her list. “We’ve lost track of this guy.” Single depth in Serenity. “He’s new to us, maybe we got the row wrong?”

I nod, pull out the binders.

“Rockin’ the old school?” she says.

I frown, puzzled.

She nods at Pipey’s ancient binders. “No computer?”

I tap the landline phone with my pen. “Just upgraded from rotary. Pretty sure the binders are here to stay.”

“Oh my gosh,” she says, “my parents are practically Amish. Cell phones give you neck cancer, no TV because it murders your brain, and computers . . . People are so mad we don’t have a website to order from, but my dad is terrified, he’s all, ‘Computers have three purposes: porn, fifteen million ways for people to steal your identity, and government spying.’ ”

Sounds a lot like Wade’s asinine logic, except in our case there’s also the part about having no money. Which I don’t mention.

Hangtown is a black hole for cell service, so I don’t actually mind the landlines. We had a computer in Mendocino, but Wade opened some Trojan horse thing, janked it up with a virus too expensive to fix so he turned it off . . . and just didn’t ever turn it back on again. His current gospel runs the way of “If binders were good enough for Pipey, they’re good enough for us!”

The girl lingers in the doorway. “Otherwise things going well?”

I turn the stiff pages of maps. Where is this guy?

“Hasn’t been long, right?” she says. “Few months?”

I nod.

“We were kind of friends with the Hoegreffs before they sold it. I haven’t met--is it your dad?”

I nod.

“Oh, so that’s fun. Family business!”

I feel myself visibly blanch.

“Well, not fun, I just mean . . . like, we have the nursery, my parents . . .” She waves at Overalls Mom, at the van out in the graves. “So I work with them instead of having to get a job at a . . . like, a taco shack or something.”

Taco shack?

“I was gone most of the summer, Habitat for Humanity internship, so now I can build anything you want with a drill and some drywall, no joke. And I’m normally only on morning deliveries when I guess you’ve been in school, so it’s . . . We’ve been ships passing in the night! But my mom told me she’s seen you. My stupid brother’s at space camp all week, so I’m filling in for him and . . . I’m just really happy to finally meet you. I’m Elanor.” She extends a small, pale hand. I scribble row M, space 81 on her list and draw a little map. Put it in her open hand. She folds it into her apron pocket.

I should say my name. Introduce myself.

“Well. Thanks,” she says. “Sorry I scared you.”

I shrug.

She leans back in the doorway.

“Smells okay in here. Better. The Hoegreffs were nice but that pipe was out of control.”

I nod.

“Okay,” she says. “Maybe I’ll see you later? Are you here a lot? Like a schedule?”

I nod.

Cold air swirls around her in the open doorway.

She pulls the list from her pocket, memorizes the plot number. “Thanks again.” She jogs back through the graves.

I watch her find the space I’ve mapped, watch her mother fill the flower can with late-season imported daffodils--expensive!--and then watch as they turn the van around and head back out through the Manderleys.

The side of the van reads: SERVING HANGTOWN--AND THE SHIRE--SINCE 1958. What on earth is “the Shire”? And how is she here in the morning--doesn’t she go to school? Not the high school anyway; there is only one in this town and I would not have missed so close an Emily doppelganger, not noticed that Princess Leia hair.

I’m so tired.

She talks so much.

But smart.

Like Emily. Too much.

Out my spying windows, I watch the ducks float aimlessly. The plain brown female ambles from the murk and takes a stroll through the babies’ headstones, the small section of lawn reserved just for infants and children, a little graveyard day care. The worst. People’s kids. That duck is stupid.

Despite Wade’s piecrust promise of “Jeez Louise, that’ll never happen on your shift, it’s all Pre-Need, old people dying in their sleep, don’t worry about it!” it’s already happened once. A kid from school. A couple of years older. I didn’t know him, but he was an idiot. I know this because he died driving drunk with a drunk bunch of other idiots, but still, how much did that suck for his parents to have to come here and buy his grave from some random kid younger than their dead son? Sixteen used to seem so old to me.

The duck strolls from the babies’ graves and nearly gets hit by a truck coming fast, gravel pinging the Manderleys. It parks at the office door.

Oh, man.

I almost wish the Rivendell van would come back.

Two men climb from the truck, shuffle in, sit heavily before me, and one of them says, “I need to bury my boy.” Then he huddles over his lap and begins to sob while I fantasize about other after-school jobs I would rather have.

That duck has cursed me.

This is At Need. At the Time of Need. It will be a single grave, single depth. The father chooses a bronze headstone that will be etched with the boy’s name, birth and death dates, and kind of a dumb poem the boy wrote last year, which at the time may have held no more significance than the obligatory fulfillment of a lame homework assignment but is now imbued with a sincere reverence. The boy is ten years old. Was.

Okay. This is the worst. Somewhere in the middle: old enough for people to really get to know him, young enough to not be a drunk-driving idiot.