Chapter One

The King of Connacht’s Daughter

I am too young to be a part of so many lies. I’d blame the bards for it, if I could. It would be easy to say that they never let the truth get in the way of a marvelous story, but my life’s tale is more complicated than that. Whose is not?

Though the bards I’ve known tell no lies, sometimes they will craft their songs without knowing all the facts. I am two summers shy of eighteen, yet they are already singing about me as if I were a grown woman and queen in my own right. (Well, I would like that, but I can’t say the same for all of their songs about me.) It almost makes me wish I were a bard myself instead of the royal princess of Connacht. Maybe then the whole truth would have a fair chance of being heard.

Above all, I hate the way they waste so much time praising how beautiful they think I am. Whether or not that’s so, it annoys…

Chapter One

The King of Connacht’s Daughter

I am too young to be a part of so many lies. I’d blame the bards for it, if I could. It would be easy to say that they never let the truth get in the way of a marvelous story, but my life’s tale is more complicated than that. Whose is not?

Though the bards I’ve known tell no lies, sometimes they will craft their songs without knowing all the facts. I am two summers shy of eighteen, yet they are already singing about me as if I were a grown woman and queen in my own right. (Well, I would like that, but I can’t say the same for all of their songs about me.) It almost makes me wish I were a bard myself instead of the royal princess of Connacht. Maybe then the whole truth would have a fair chance of being heard.

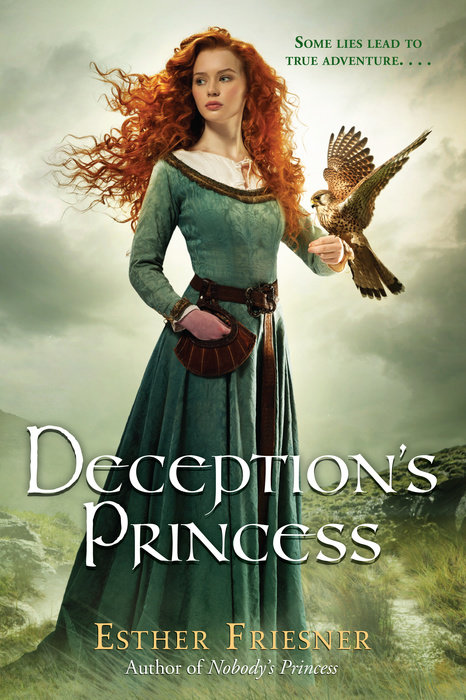

Above all, I hate the way they waste so much time praising how beautiful they think I am. Whether or not that’s so, it annoys me. The flash of sunlight on a sword blade is also beautiful, but it distracts you from seeing the worth of the steel. As if I were nothing but the sum of eyes and lips, height and grace, slenderness and strength, fair skin and fiery hair! I am much more than that: I am Maeve.

If I had my sister Derbriu’s gift for music, I’d make sure my true story reached every ear in the length and breadth of Eriu, from the High King’s seat at Tara to the humblest farmer’s hut. I know exactly how I’d begin it too. I’d start with what happened on that spring morning some dozen years ago when I danced with the black bull.

I didn’t think it was a matter of any importance when I did it, but what did I know? I was five years old. I’ve been called Maeve the Spoiled, Maeve the Proud, Maeve the Sneak, and, worst of all, Maeve Two-Tongues, Maeve the Liar. Nobody ever called me Maeve the Wise, then or now. One small adventure, done on a whim, and it changed my world forever.

The black bull was my father’s pride, a prize taken in one of the countless cattle raids he led against our neighbors. A king must show his strength as a warrior by capturing the cattle of lesser men. To me, that meant my father was obliged to steal every herd in the land. As far as I was concerned, all men were inferior to Eochu, royal lord of the realm of Connacht, which he ruled from within the ringfort of Cruachan.

In those days, I didn’t think of Cruachan as a fortress. It was simply my home. One could enter its walls of beaten earth only through a single narrow gateway. The king’s great house and many other buildings stood safe within. I knew nothing of the importance of making a stronghold hard to attack, easy to defend. As far as I was concerned, Cruachan’s battlements were placed atop a high mound strictly for my pleasure, so that I could enjoy a fine view of the surrounding countryside. And the armed men on watch? Obviously their sole purpose was to make sure I didn’t slip off the wall.

On the morning I crossed paths with the black bull, Father had set out on yet another raid, or so I thought. All the house rose early, a few of our warriors groaning pitiably from the effects of the previous night’s leave-taking feast. Too soon for me, Father finished breakfast and strode off, bawling for his chariot driver, Fechin, to attend him. The warriors of Connacht grabbed a few last mouthfuls of meat and bread before following their leader. They were as eager to race into battle as their high-spirited horses. I overheard some of them boasting about how they would shine in battle and come home to claim the hero’s portion, the best cut of roasted meat served at the victory banquet.

My mother, Cloithfinn, matched Father pace for pace all the way to his waiting chariot, her hip-length waves of golden hair swinging like a heavy silken cloak. My five sisters were already there, lingering beside the king’s horses. There were kisses for us all. I wanted to cry, but the air was already loud with the wailing of many young women, clinging to their sweethearts. Mother wouldn’t embarrass Father like that. She carried herself tall and proud, with a cheerful face, and held us to her example. We knew this might be the last time we would see our father alive, but we were a king’s daughters and we had to be brave.

As Father’s chariot passed through the gateway and down the steep side of Cruachan’s mound, Mother led us to the top of the wall. We stood with the other women, shouting encouragement to our departing heroes. The weather cut short our farewells; a barrier of fog settled over the land, so that Father and his followers vanished from sight quickly, as if the Fair Folk had risen from the Otherworld and swathed them in capes of silk, cold and gray.

My favorite sister, Derbriu, squeezed my hand as we all began our descent from the battlements. “Are you all right, Maeve, dearest?” She often spoke to me in that motherly way. If there’s one truth I know in the world, it’s this: five sisters are four too many if they tease you all the time for being the baby of the family. Derbriu never did. Until my birth, three years after hers, she’d been the youngest, so she knew how much those taunts of “Baby!” stung.

I smiled, just for her. “I’m fine.”

She knew I was lying. “You mustn’t fret while Father’s gone. Think of how happy we’ll be when we see him home safe again.”

“I’ll be happy for that,” I said solemnly. “And because of the cows.”

Derbriu laughed so hard it drew our eldest sister’s attention. “What’s so funny?” Clothru asked.

“Maeve’s eager to get the cows Father promised us.”

“Well, so am I,” said Eithne and Eile in chorus. Our twin sisters often spoke with one voice. It always made me giggle.

“And I!” our middle sister, Mugain, exclaimed. “Five cows apiece for doing next to nothing? It’s a windfall.” She grinned with delight.

Mother overheard. “Don’t count your cows too soon, my girls--not with the easy way you all fall to bickering. Your father’s so fed up with it, he’s willing to buy peace. Five cows for each of you if he finds you little she-wolves lying down in friendship when he comes home.” The severe look she gave us added: See that it happens.

“Do we get to choose?” I piped up.

“Choose?” Mugain echoed, raising her eyebrows.

I folded my arms. “They’ll be my cows. I want to pick them.”

She snickered. “You can hardly wipe your own nose, Maeve. When did you become a judge of cattle?”

“Tame your tongue, Mugain,” Mother snapped. “This is how quarrels start. Maeve has a good point: you girls should have a hand in matters that affect your future. I’m not raising you to be helpless or lazy or to expect you’ll lead perfect lives simply because you’re princesses. My daughters will not be empty bowls, waiting idly for someone else to decide if you’ll hold the hero’s portion or scraps for dogs. It’s not enough to be given things. You must also--”

“So you want us to pick our own cows, Mother?” I interrupted, grabbing her arm and bouncing up and down. “Can we? Will you promise?”

“She can’t do that, Maeve,” Clothru said in her most annoying I-know-everything voice. “She has to ask Father.”

Mother’s eyes flashed at my eldest sister. “Beg his permission to give my word? Your father will honor my pledge because he honors me. And if you girls wish to be respected by your husbands when you’re grown up, gone, and managing your own households, you will take care to--”

I didn’t linger to hear the rest of Mother’s lecture. Whenever she started talking of husbands, I knew she couldn’t mean me. I didn’t want one, not if being married meant leaving home, not as long as my life held so many more interesting things to do.

I might never want a husband, but I did want a knife, and now. I stole away so nimbly that not even Derbriu noticed my departure. I sneaked into the great hall and spirited off a small, keen-edged blade from the place where the women prepared our meals. My plan was simple: find five cows that I’d be proud to own and cut off half the tuft of coarse hair at the end of their tails to mark them as mine.

The need for haste blinded me to all else. If I waited, one of my sisters might get a cow I wanted. I didn’t spare a moment to take off the fine clothes I’d worn for Father’s leave-taking or waste a thought over how dangerous cattle could be.

As I said, no one ever called me Maeve the Wise.

I plunged into the fog that had swallowed up Father’s raiding party, happy to have it conceal my departure from Cruachan, but once I reached the grazing fields, my elation faded. The mist wasn’t burning off fast enough to suit me. How was I supposed to choose cows I couldn’t see? I wanted to stamp in frustration, but cold droplets soaked the hem of my tunic and dense grass hampered my feet. I scowled into the haze and struggled on. The thick, unmistakable smell of cattle was all I had to guide me along.

And then, between one step and the next, I met the bull. He loomed through the slowly thinning fog like one of the Fair Folk’s stone monuments leading to the Otherworld. A feeble glimmer of sunlight made his black-tipped horns glow with an unearthly light. He was less than seven paces away and seemed unconcerned by my presence. I could have flung a pebble and hit his flank easily, but I would have died before committing such sacrilege. His glorious strength and lordly presence stole my breath. I knew that I had to have him.

The bull was grazing as I crept closer. From time to time he lifted his heavy head and turned it slowly from side to side as if sifting the different scents on the morning air. When he did this, I froze in place, willing him to mistake me for a part of the landscape. I wasn’t a complete fool: I understood that what I wanted to do was perilous. Now that I saw the full measure of the beast before me, I recognized him. This was not just any of my father’s cattle. This was Dubh, the fire-hearted black bull whose horns had laid open a man’s leg from hip to knee when Father first brought the creature home. This was the one whose blood ran so hot that our cowherds had to keep him far from the other cattle outside of breeding time.

This was the bull I was born to own.

I slipped off my tunic and tied the sleeves loosely around my neck. If I suddenly had to turn and run, I couldn’t have that dew-drenched garment holding me back. But it wasn’t just any tunic of wool or linen, to be dropped in the field and retrieved later--if the bull’s hooves spared it. I’d chosen to wear my best one for Father’s leave-taking, a family treasure made from silk the deep blue of twilight.

The tunic’s soaking hem fell against the backs of my thighs and clung there. That didn’t matter; my legs were free. I was ready. My palms grew damp, my mouth dry. I licked my lips; it didn’t help. The bull continued grazing. I edged closer, coming up behind him. A misstep plunged my right foot into one of his droppings. I think the familiar stink of his own waste masked my true scent just long enough for me to lift his tail and slash a chunk free with my blade.

Oh, how I ran after that! I raced through the grass, one foot a reeking mess, one hand clutching the precious spoils of my adventure. My heart pounded in my ears, but not half as loud as the rumble of the bull’s hooves. I’d struck swiftly, but not swiftly enough to escape undetected. Great Dubh knew he’d been challenged, and he bawled his outrage to the skies. I didn’t look back, but I could hear him closing the gap between us. Now the morning mist was lifting and I could see Cruachan’s high earthen walls in the distance. A stand of trees sprang up to my right, but too far off for me to reach them before the black bull reached me. From the left I heard the lowing of many cows as the king’s herds were driven to milking. Those were the beasts I’d been seeking when I found the bull. If I could reach them and lose myself in the herd, I might survive Dubh's charge. Could my small legs cover so much distance in time?

I clenched my teeth and drew in deep, desperate breaths through my nostrils. As hard as I ran, as dire as the fate at my heels, I never let go of the tuft of bull’s hair in my left hand. I won’t give it up! I thought angrily. It’s proof he’s mine! And if he overtakes me, I’ll . . . I’ll . . . My right hand closed more tightly on the little knife. In my heart I knew that even if I managed to stab the maddened bull with that pitiful blade, it would be no more to him than a fly’s bite. Still I clung to false notions that I was not entirely helpless. I stoked my fury like a blacksmith’s fire until it blazed away the panic in my bones.

The sound of many voices raised in fear came from across the fields: my father’s cowherds. The sun had erased the last of the mist, giving them a clear view of my wild, hopeless dash. They were horrified but too far off to help me. Even if they could have conjured wings and covered the space between us, would they have been able to stop the beast? They’d have had better luck using a reed to hold back a thunderstorm!

My chest tightened and burned. I stepped on a tuft of grass and staggered sideways, stumbling halfway to my knees but recovering quickly. Something tugged at my left foot as I rose. I kicked backward violently, thrusting clear of whatever had snared me, and ran on.

It wasn’t until I’d covered forty strides that I became aware of the change all around me. The cowherds’ cries of alarm had turned to cheers. The bull’s ever-closer presence was fading. The sun and wind poured over my back, which was now bare as an egg, and my neck was no longer encircled by the silk tunic’s sleeves. What was happening? I couldn’t resist the temptation to pause in my flight and turn around. Dubh the Mighty, Dubh the Fierce, Dubh the Bull of Bulls, my father’s most valued beast, no longer chased me. Instead of plunging on, eager to avenge his clipped tail with my blood, the huge animal was trampling and goring and tearing the life out of . . . my tunic. Most of it lay in a damp wad under his hooves, the rich blue silk a muddy brown. A scrap of fabric trailed from one of his horns, forever just out of reach, tormenting him. He bawled and shook his head, but it was there to stay.