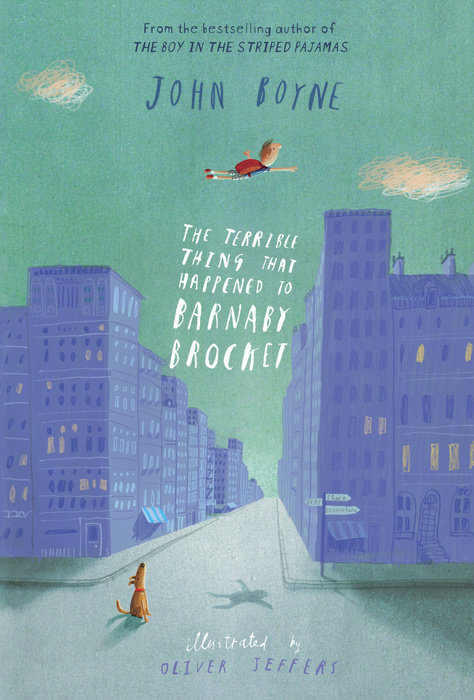

The Terrible Thing that Happened to Barnaby Brocket

Barnaby Brocket is an ordinary 8-year-old boy in most ways, but he was born different in one important way: he floats. Unlike everyone else, Barnaby does not obey the law of gravity. His parents, who have a horror of being noticed, want desperately for Barnaby to be normal, but he can't help who he is. And when the unthinkable happens, Barnaby finds himself on a journey that takes him all over the world. From Brazil to New York, Canada to Ireland, and even to space, the floating boy meets all sorts of different people—and discovers who he really is along the way.

This whimsical novel will delight middle graders, and make readers of all ages question the meaning of normal.

An Excerpt fromThe Terrible Thing that Happened to Barnaby Brocket

Chapter 1

A Perfectly Normal Family

This is the story of Barnaby Brocket, and to understand Barnaby, first you have to understand his parents: two people who were so afraid of anyone who was different that they did a terrible thing that would have the most appalling consequences for everyone they loved.

We begin with Barnaby's father, Alistair, who considered himself to be a completely normal man. He led a normal life in a normal house, lived in a normal neighborhood where he did normal things in a normal way. His wife was normal, as were his two children.

Alistair had no time for people who were unusual or who made a show of themselves in public. When he was sitting on a Metro train and a group of teenagers were talking loudly nearby, he would wait until the next stop, jump off, and move to a different carriage before the doors could close again. When he was eating in a restaurant--not one of those fancy new restaurants with difficult menus and confusing food; a normal one--he grew irritated if his evening was spoiled by waiters singing "Happy Birthday" to some attention-seeking diner.

He worked as a solicitor at the firm of Bother & Blastit in the most magnificent city in the world--Sydney, Australia--where he specialized in last wills and testaments, a rather grim employment that suited him down to the ground. It was a perfectly normal thing, after all, to prepare a will. Nothing unusual in that. When clients came to see him in his office, they often found themselves a little nervous, for drawing up a will can be a difficult or distressing matter.

"Please don't upset yourself," Alistair would say on such occasions. "It's perfectly normal to die. We all have to do it one day. Imagine how awful it would be if we lived forever! The planet would collapse under all that excess weight."

Which is not to say that Alistair cared very much about the planet's welfare; he didn't. Only hippies and New Age types worried about things like that.

There is a belief held by some, particularly by those who live in the Far East, that each of us--you included--comprises one half of a couple separated before birth in the vast and complex universe, and that we spend our lives searching for that detached soul who can make us feel whole again. Until that day comes, we all feel a little out of sorts. Sometimes completeness is found through meeting someone who, on first appearances, seems to be the opposite of who we are. A man who likes art and poetry, for example, might end up falling in love with a woman who spends her afternoons up to her elbows in engine grease. A healthy-eating lady with an interest in outdoor sports might find herself drawn to a fellow who enjoys nothing more than watching them from the comfort of his living-room armchair with a beer in one hand and a sandwich in the other. It takes all sorts, after all. But Alistair Brocket always knew that he could never share his life with someone who wasn't as normal as he was, even though that in itself would have been a perfectly normal thing to do.

Which brings us to Barnaby's mother, Eleanor.

Eleanor Bullingham grew up on Beacon Hill, in a small house overlooking the northern beaches of Sydney. She had always been the apple of her parents' eyes, for she was indisputably the best-behaved girl in the neighborhood. She never crossed the street until the crossing guard appeared, even if there wasn't a car anywhere in sight. She stood up to let elderly people take her seat on the bus, even if there were dozens of empty seats already available to them. In fact, she was such a well-mannered little girl that when her grandmother Elspeth died, leaving her a collection of one hundred vintage handkerchiefs with her initials, EB, carefully embroidered onto each one, she resolved one day to marry a man whose surname also began with B in order that her inheritance would not go to waste.

Like Alistair, she became a solicitor, specializing in property work, which, as she told anyone who asked her, she found frightfully interesting.

She accepted a job at Bother & Blastit almost a year after her future husband, and was a little disappointed at first when she looked around the office to discover how many of the young men and women employed there were behaving in a less-than-professional manner.

Very few of them kept their desks in any sort of tidy condition. Instead, they were covered with photographs of family members, pets, or, worse, celebrities. The men tore their used takeaway coffee cups into shreds as they talked loudly on the telephone, creating an unsightly mess for others to clean up later, while the women appeared to do nothing but eat all day, buying small snacks from a trolley that reappeared every few hours laden down with sweet treats in brightly colored packaging. Yes, this was normal behavior by the current standards of what was normal, but still, it wasn't normal normal.

At the beginning of her second week at the firm, she found herself walking up two flights of stairs to a different department in order to deliver a hugely important document to a colleague who needed it without a moment's delay or the whole world would grind to a halt. Opening the door, she tried not to stare at the signs of disorder and squalor that lay before her in case it made her regurgitate her breakfast. But then, to her surprise, she saw something--or someone--who made her heart give the most unexpected little leap, like an infant gazelle hurdling triumphantly across a stream for the first time.

Sitting at a corner desk, with a neat pile of paperwork before him separated into color-coded groups, was a rather dashing young man, dressed in a pinstripe suit and sporting neatly parted hair. Unlike the barely house-trained animals who were working around him, he kept his desk tidy, the pens and pencils gathered together in a simple storage container, his documents laid out efficiently before him as he worked on them. There wasn't a picture of a child, a dog, or a celebrity anywhere in sight.

"That young man," she asked a girl sitting at the desk closest to her, stuffing her face with a banana nut muffin, the crumbs falling across her computer keyboard and getting lost forever between the keys. "The one sitting in the corner. What's his name?"

"You mean Alistair?" said the girl, running her teeth along the inside of the wrapper just in case there was any sticky toffee sauce left behind. "The most boring man in the universe?"

"What's his surname?" asked Eleanor hopefully.

"Brocket. Rotten, isn't it?"

"It's perfect," said Eleanor.

And so they were married. It was the normal thing to do, particularly after they had been to the theater together (three times); a local ice cream parlor (twice); a dance hall (only once; they hadn't liked it very much--far too much jiving going on, too much of that nasty rock-and-roll music); and on a day trip to Luna Park, where they took photographs and made pleasant conversation until the sun began to descend and the lights gleaming from the clown's giant face made him look even more terrifying than usual.

Exactly a year after their happy day, Alistair and Eleanor, now living in a normal house in Kirribilli on the Lower North Shore, welcomed their first child, Henry, into the world. He was born on a Monday morning on the stroke of nine o'clock, weighed precisely seven pounds, and appeared after only a short labor, smiling politely at the doctor who delivered him. Eleanor didn't cry or scream when she was giving birth, unlike some of those vulgar mothers whose antics polluted the television airwaves every night; in fact, the birth was an extremely polite affair, ordered and well mannered, and nobody took any offense at all.

Like his parents, Henry was a very well-behaved little boy, taking his bottle when it was offered to him, eating his food, looking absolutely mortified whenever he soiled his nappy. He grew at a normal rate, learning to speak by the time he turned two and understanding the letters of the alphabet a year later. When he was four, his kindergarten teacher told Alistair and Eleanor that she had nothing good or bad to report about their son, that he was perfectly normal in every way, and as a reward they bought him an ice cream on the way home that afternoon. Vanilla-flavored, of course.

Their second child, Melanie, was born on a Tuesday three years later. Like her brother, she presented no problems to either nurses or teachers, and by the time her fourth birthday had arrived, when her parents were already looking forward to the arrival of another baby, she was spending most of her time reading or playing with dolls in her bedroom, doing nothing that might mark her out as different from any of the other children who lived on their street.

There was really no doubt: the Brocket family was just about the most normal family in New South Wales, if not the whole of Australia.

And then their third child was born.

Barnaby Brocket emerged into the world on a Friday, at twelve o'clock at night, which was already a bad start, as Eleanor was concerned that she might be keeping the doctor and nurse from their beds.

"I do apologize for this," she said, perspiring badly, which was embarrassing. She had never perspired at all when giving birth to Henry or Melanie; she had simply emitted a gentle glow, like the dying moments of a forty-watt bulb.

"It's quite all right, Mrs. Brocket," said Dr. Snow. "Children will appear when they appear. We have no way of controlling these things."

"Still, it is rather rude," said Eleanor before letting loose a tremendous scream as Barnaby decided that his moment was upon him. "Oh dear," she added, her face flushed from all these exertions.

"There's really nothing to worry about," insisted the doctor, getting himself into position to catch the slippery infant--rather like a rugby player stepping back on the field of play, one foot rooted firmly in the grass behind him, the other pressed forward in the soil, his two hands outstretched as he waits for the prize to be thrown in his direction.

Eleanor screamed again, then lay back, gasping in surprise. She felt a tremendous pressure building inside her body and wasn't sure how much longer she could stand it.

"Push, Mrs. Brocket!" said Dr. Snow, and Eleanor screamed for a third time as she forced herself to push as hard as she could while the nurse placed a cold compress on her forehead. But rather than finding this a comfort, she began to wail loudly and then uttered a word she had never uttered in her life, a word that she found extremely offensive whenever anyone at Bother & Blastit employed it. It was a short word. One syllable. But it seemed to express everything she was feeling at that particular moment.

"That's the stuff," cried Dr. Snow cheerfully. "Here he comes now! One, two, three, and then a final giant push, all right? One . . ."

Eleanor breathed in.

"Two . . ."

She gasped.

"Three!"

And now there was a terrific sensation of relief and the sound of a baby crying. Eleanor collapsed back on the bed and groaned, glad that this horrible torture was over at last.

"Oh dear me," said Dr. Snow a moment later, and Eleanor lifted her head off the pillow in surprise.

"What's wrong?" she asked.

"It's the most extraordinary thing," he said as Eleanor sat up, despite the pain she was in, to get a better look at the baby who was provoking such an abnormal response.

"But where is he?" she asked, for he wasn't being cradled in Dr. Snow's hands, nor was he lying at the end of the bed. And that was when she noticed that both doctor and nurse were not looking at her anymore, but were staring with open mouths up toward the ceiling, where a newborn baby--her newborn baby--was pressed flat against the white rectangular tiles, looking down at the three of them with a cheeky smile on his face.

"He's up there," said Dr. Snow in amazement, and it was true: he was. For Barnaby Brocket, the third child of the most normal family who had ever lived in the Southern Hemisphere, was already proving himself to be anything but normal by refusing to obey the most fundamental rule of all.

The law of gravity.

Chapter 2

The Mattress on the Ceiling

Barnaby was discharged from hospital three days later and brought home to meet Henry and Melanie for the first time.

"Your brother's a little different from the rest of us," Alistair told them over breakfast that morning, choosing his words carefully. "I'm sure it's only a temporary thing but it's very upsetting. Just don't stare at him, all right? If he thinks he's getting a reaction, it will only encourage his foolishness."

The children looked at each other in surprise, unsure what their father could possibly mean by this.

"Does he have two heads?" asked Henry, reaching for the marmalade. He liked a bit of marmalade on his toast in the mornings. Although not in the evenings; then, he preferred strawberry jam.

"No, of course he doesn't have two heads," replied Alistair irritably. "Who on earth has two heads?"

"A two-headed sea monster," said Henry, who had recently been reading a book about a two-headed sea monster named Orco, which had caused any amount of mayhem beneath the Indian Ocean.

"I can assure you that your brother is not a two-headed sea monster," said Alistair.

"Does he have a tail?" asked Melanie, gathering up the empty bowls and stacking them neatly in the dishwasher. The family dog, Captain W. E. Johns, a canine of indeterminate breed and parentage, looked up at the word tail and began to chase his own around the kitchen, spinning in a circular direction until he fell over and lay on the floor, panting happily, delighted with himself.

"Why would a baby boy have a tail?" asked Alistair, sighing deeply. "Really, children, you have the most extraordinary imaginations. I don't know where you get them from. Neither your mother nor I have any imagination at all, and we certainly didn't bring you up to have one."

"I'd like to have a tail," said Henry thoughtfully.

"I'd like to be a two-headed sea monster," said Melanie.

"Well, you don't," snapped Alistair, glaring at his son. "And you aren't," he added, pointing at his daughter. "So let's just get back to being normal human beings and make sure this place is spick-and-span, all right? We have a guest coming this morning, remember."

"But he's not a guest, surely," said Henry, frowning. "He's our little brother."

"Yes, of course," said Alistair after only the briefest of pauses.