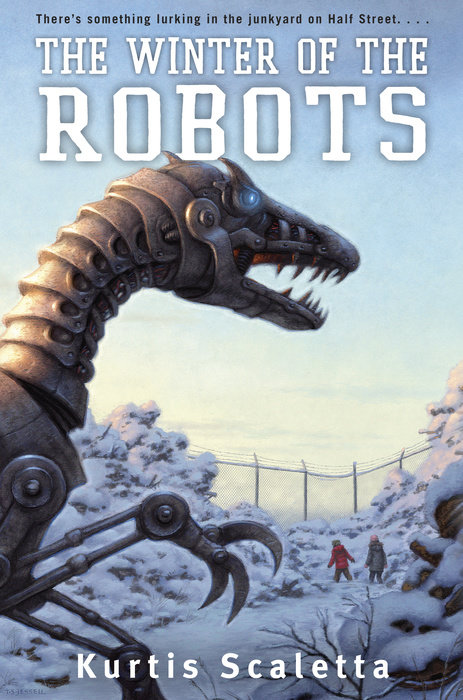

The Winter of the Robots

Seven feet of snow, four science-fair nerds, one creepy junkyard.

Get ready for the ultimate robot battle.

Jim is tired of being the sidekick to his scientific genius, robot-obsessed, best friend Oliver. So this winter, when it comes time to choose partners for the science fair, Jim dumps Oliver and teams up with a girl instead. Rocky has spotted wild otters down by the river, and her idea is to study them.

But what they discover is bigger—and much more menacing—than fuzzy otters: a hidden junkyard on abandoned Half Street. And as desolate as it may seem, there's something living in the junkyard. Something that won't be contained for long by the rusty fences and mounds of snow. Can Jim and Rocky—along with Oliver and his new science-fair partner—put aside their rivalry and unite their robot-building skills? Whatever is lurking on Half Street is about to meet its match.

An Excerpt fromThe Winter of the Robots

Chapter 1

None of this would have happened if I hadn’t picked a girl over a robot.

On the first day of school after winter break, Mr. Cole, our science teacher, hit us with a big assignment: the school science fair. We were supposed to pair up. As usual, my partner was Oliver. He’d been my best friend since we were toddlers.

“So what do you want to do, another robot?” I asked him on the bus ride home. Last year, our project was a three-foot-tall robot that steamrolled a papier-mache diorama of Minneapolis. Oliver made the robot, and I made the diorama. The project won an honorable mention, which was good for sixth graders. Now that we were in seventh grade, Oliver wanted to win a first-place ribbon and compete at the district science fair.

“Yeah, I want to make another robot,” he said. “A better robot.”

The bus rumbled to a stop, and the door opened to let in a blast of icy air, but nobody got off. The bus was mostly empty. There was a home basketball game, and all of the normal kids had stayed after school to watch it. All of the normal kids, that was, except for Rochelle. She lived on my block, but I didn’t know her that well. She caught me looking at her and waved. I looked back at Oliver.

“Can we do the same thing twice in a row?” I was only half interested in the conversation now. Rocky--that was what kids called her--Rocky waving at me was distracting. Girls didn’t usually wave at me. I wondered what it meant, if anything. Was she saying, “Hey, caught you checking me out”? Or was she was saying, “Howdy, neighbor”? Maybe it was nothing.

“We’re not doing the same thing,” said Oliver. It took me a moment to remember what he was talking about. “We’re going to make a completely new robot.”

“It’s the same idea.”

“That’s what scientists do. They revise an idea, evolve it, and make it better.” Both of Oliver’s parents were scientists, so he would know. He was a mad scientist in training. He already had the brilliant mind, the wild hair, and the thick glasses. All he needed was a hunchbacked assistant.

The bus turned onto the bridge across the Mississippi River. The houses were smaller on our side of the river, a bit more run-down and closer together. North Minneapolis is considered the worst part of Minneapolis, but we lived in the nicest part of North, in a neighborhood called Camden. Mom says it’s the Edina of North Minneapolis. You have to be from around here to get that joke.

Rocky looked intently out the window, searching the riverbanks. If I had any courage, I would have shouted out something witty--“Lose a contact lens down there?”--but I didn’t. She caught me looking at her again. This time she didn’t wave, but she did smile.

“What will the robot destroy this time?” I asked Oliver. His robots always destroyed stuff. His ideal project would probably be an eight-foot-tall robot that stormed around the auditorium smashing all the other projects to smithereens.

“That’s the great part,” he said. “We’ll pit it against last year’s robot.”

“You’d let Robbie get beat up?”

“It’s a machine, Jim. You can’t get sentimental.”

“I don’t see the point.”

“It’s more challenging. The cityscape tested the robot’s mobility, but it didn’t fight back. What I really like is robot battles. I would have done it last year, but I didn’t have time to build two robots.”

“I mean, I don’t see why it has to destroy anything. Why can’t it . . . fold laundry or something?”

“You sound like my mother,” he said.

“I sound like a guy who has to do his own laundry.” I stole another look at Rocky, but now all I could see was the back of her head.

“Battles are more theatrical,” he explained. “That’s all.”

“What am I going to do?”

“Good question.” He didn’t come up with an answer before the bus stopped to let him off.

“Do you want to come over?” he asked. “We could get started.”

“Nah. I have to move a snowbank before dark.”

“OK. I’ll email you some sketches.” As the bus pulled out again, I watched him hurry down the icy sidewalk toward home, with his hands stuffed in his pocket and his knit hat not quite straight on his head.

He did have an assistant, I realized. He had me.

I didn’t have a hunched back yet, but I would by the end of the winter. Dad made me do all the shoveling, and it was the snowiest winter in Minneapolis since I’d been born. There was a six-foot pile of snow by the driveway where I’d dumped all the snow so far. Now I had to move the entire mountain before it snowed again; otherwise, there would be no place to put the new stuff.

The next bus stop was right in front of my house. I dropped my backpack inside and went straight for the shovel. An hour later I was already hurting, and I’d barely made a dent. Why didn’t Oliver build a robot that shoveled snow? I wondered.

“Hey,” said a girl’s voice behind me. I lowered the shovel and turned around. It was Rocky.

“Hey,” I said. “You aren’t at the game?” Like I hadn’t even noticed her on the bus.

“Nah,” she said. “You don’t have a snowblower?” She eyed the metal storage shed sitting on our lawn next to the garage.

“Nope. That’s my dad’s stuff,” I said. “He sells--”

“Security systems, I know. He keeps trying to talk my dad into buying one.”

“Ha. Sorry about that.”

“Don’t be,” she said. “Do you want to borrow our blower?”

“Is it cool with your dad?”

“Oh, he’d freak if he knew, but he won’t be home until after midnight.”

“Um . . .”

“I’m kidding!” she said. “Seriously, it’s fine.”

“Thanks. Seriously, that would be awesome.”

“Just being neighborly,” she said.

Even if I’d known she was setting me up, I would have used the snowblower.

My little sister Penny was waiting for me inside. She’s in third grade.

“You cheated!” she said.

“Cheated on what?”

“You used the neighbors’ snow machine.”

“So what? Dad wants me to clear the driveway. He never said I had to shovel it.”

“So you don’t mind if I tell him?”

“Nope. Go right ahead.”

I saw her eyes dim and then brighten.

“What if I told the neighbor?”

“She said I could use the blower.”

“You talked to the girl. Not Mr. Battleship. It’s his machine.”

The neighbors’ name was Blankenship, but Battleship would have been a good name for Rocky’s dad. He was huge.

“All right. What do you want to keep your mouth shut?”

“I don’t know. Something good.”

“I’ll watch that DVD with you, if you want,” I suggested. She’d gotten one for Christmas we’d already seen a hundred times. Something about a princess and her champion horse who was really a guy who’d been turned into a horse by a witch. I sat through it twice in a row on New Year’s Eve so she wouldn’t tell Mom and Dad I watched a horror movie on cable.

“Nah,” she said. “I’ll decide later.”

Penny had a hole in her heart when she was born, but they didn’t discover it until she was three. She didn’t have the energy toddlers were supposed to have, so a doctor ran some tests. He could tell that her heart was pumping some used‑up blood back into her body before it got fresh oxygen. They did an X-ray and saw a tiny hole. Penny had to have surgery to patch it up. Mom and Dad and everybody else kept saying everything would be OK, and it turned out they were right, but it didn’t feel OK at the time--not to me. I figured they were telling me that because I was an eight-year-old.

I didn’t see her at the hospital until after the operation. I spent the night with Aunt Ingrid, and we went to see Penny the next day. She looked so small and scared in the kid-sized bed. She had wires and tubes coming out of her. Until then I’d been jealous of her and annoyed by her and occasionally awed by her, but that was the first time I realized I loved her. I knew I was supposed to, but that was the first time I felt it. She’s fine now, but she gets checked up once a month to make sure her blood is getting enough oxygen and her heart is beating right. Anyway, that’s why I don’t mind letting her push me around. Besides, she only asks me to do stuff with her. It’s not like she asks me for money. It’s not like I had any to give her, if she did.

Oliver IM’d me that evening.

Oliver: I know what u can do! U can make dummy robots. New robot can battle them. Save Robbie for the district competition.

Jim: Make them out of what?

Oliver: Shoeboxes & tinfoil. I’ll put a little motor in so they can run away, etc.

Jim: Why is my part always arts & crafts?

Oliver: lol

Jim: Not kidding.

Oliver: lol anyway.

Jim: W

Oliver: Just trying to help.

Jim: Maybe I’ll come up with my own project.

Oliver: Come on.

Jim: Srsly.

Oliver: We need partners. U know that. Teams of 2.

Jim: I know. I mean w/someone else.

Oliver: Like who?

A second chat window popped up.

Rochelle: Do you have a partner for science fair?

Jim: Talking to Oliver about it now. Nothing def.

Rochelle: I have a cool idea. Want in?

Jim: Srsly? U want to be partners?

I waited for the explanation. “Rochelle is typing,” the status bar told me, but nothing came up. I checked the chat with Oliver in the meantime. He’d left a series of messages.

Oliver: Who is ur partner?

Oliver: There’s nobody. Admit it.

Oliver: Where are you?

Oliver: Fine, be that way.

The last message told me he was now off-line. I closed the window and went back to the chat with Rocky.

Rochelle: You have something I need.

Jim: Like what?

There was another pause. I was about to fire off a “?” when she came clean.

Rochelle: I need cams. U prolly have some.

It all made sense now. Why she lent me the snowblower. The way she eyed the storage shed.

Rochelle: Is that doable?

Jim: Maybe. What for?

Rochelle: I want to monitor urban wildlife.

Jim: Like what? Squirrels? Crows?

Rochelle: Otters. They live right here in the Miss. River. It would be super cool to study them.

I thought it over. I needed more friends in my life. Plus, I wanted to be equal partners with someone instead of taking orders from Oliver. On the other hand, there was no way Dad would let me use the cameras. On the other other hand, being seen with a girl would improve my status by about 8,000 percent. Plus, we’d hang out together. The thought made my heart pound.

Dad wouldn’t give me permission to use the cameras, but I could borrow them for a few days and put them back. He would never know they were gone.

Jim: I’m in.

Rochelle: Terrific. It’ll be fun, I promise.

Chapter 2

“Your science project is to look at fuzzy little animals?” said Oliver. I’d waited until lunchtime to tell him that I was swapping partners.

“What’s wrong with studying animals?”

“It doesn’t sound very scientific.”

“We’re observing animals and studying their behavior. Scientists do that, you know. Ever heard of Jane Goodall?”

“Obviously,” he said, flicking the question away with his hand. “But it’s not a science project unless you’re trying to prove something.”

“Says you.”

“Says the rules,” he said. He dug through his backpack and found the handout Mr. Cole had given us. “ ‘Hypothesis,’ ” he said, pointing at the top of the project description. “That’s what you’re trying to prove. It says right here: ‘You should solve a problem or test a theory, not simply report information.’ ”

“So we’ll come up with a hypothesis,” I told him.

“How are you going to do it, anyway?” he asked. “Camp on the riverbank? Wait until the otters accept you as one of their own?”

“Why are you being such a jerk about this?”

“Because now I don’t have a partner,” he grumbled.

“Ask someone else. They’d be happy for the easy A.”

“I don’t want to work with anyone else. Besides, they all have partners by now.”

“There are twenty kids in the class,” I reminded him. “Somebody needs a partner.”

“Great. Watch me get stuck with the dumbest kid in class.”

“Too late for that,” I said. “I have a partner, remember?”

“Ha.” He got up to leave, grabbing his tray. I grabbed my own and followed him to the garbage cans to dump the leftovers.

“So what’s your hypothesis?” I asked.

“That by incorporating a gyroscopic accelerometer, the robot will have better mobility and better balance than the robot from last year. That radially swinging hammers are more effective at combat than forward-thrusting fists. That a polyurethane chassis filled with fiberglass foam can withstand more damage than a hollow metallic chassis. That--”

“That you can come up with more hypotheses than anyone else. Got it.”

“It’s all wrapped around a simple, central hypothesis,” he said.

“That you can make a robot that will kick the butt of any other robot.”

“Exactly.”

Oliver didn’t get stuck with the dumbest kid in class. He got stuck with the scariest: Dmitri Volkov.

Dmitri was huge, shaved his head, and wore clomping boots all year round. His family was from Russia. He must have been our age, but he seemed to be ten years older. He moved silently through the halls, a shark among guppies. There were rumors about him: that his dad was in the Russian mafia, and that Dmitri himself had been in trouble with the law. That he should have gone to reform school, but his dad had pulled strings. He was in the advanced classes and made the honor roll every quarter. That made him scarier. He was not a mere hoodlum, but a true super-villain in the making.

He only ever said two words to me--he was walking by me when I was at my locker, and stepped on my toe. “Excuse me,” he’d said, but in such a flat way I still wasn’t sure if he’d meant it. It was the kind of thing a bully would do, but Dmitri didn’t have the reputation of being a bully. That seemed beneath him. He was into deeper and more dangerous things than pushing kids around.

When Mr. Cole asked who didn’t have a partner yet, the only two hands that went up were Oliver’s and Dmitri’s. I’d left Oliver hanging on to a rope that turned out to be tied around the neck of a grizzly bear.