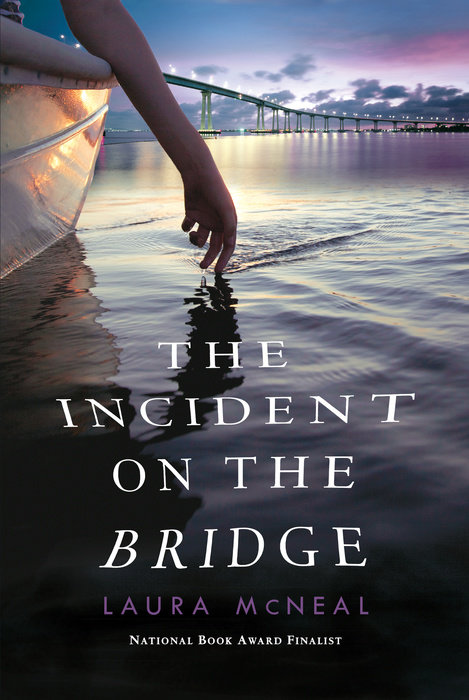

The Incident on the Bridge

From National Book Award nominee Laura McNeal comes a gripping, tautly told novel that is at once hopeful and harrowing, and perfect for fans of We Were Liars and Bone Gap.

When Thisbe Locke is last seen standing on the edge of the Coronado Bridge, it looks like there is only one thing to call it. But her sister, Ted, is not convinced. Despite the witnesses and the police reports and the divers and the fact that she was heartbroken about the way things ended with Clay and how she humiliated herself at that party, Thisbe isn’t the type of person to wind up just an “incident.”

While everyone in town prepares to mourn the loss (some more than others), Ted—along with Fen, the new kid in town—sets out to put the pieces together and find her sister.

But if Thisbe didn’t jump, what happened up on that bridge?

"McNeal writes with a mature hand, expert pacing, and an immediacy that ensures readers will be engrossed.” —Publishers Weekly, starred review

“An evocative tale of regret and redemption.” —Booklist

“Expert pacing will keep readers turning the pages until they know Thisbe’s fate.” —Kirkus

An Excerpt fromThe Incident on the Bridge

1

Impulse

Thisbe had to stop. She had to quit obsessing about Clay and Jerome and college and ride her bike down to Glorietta Bay, where she always felt better, where she had researched and written “The Effect of Pleasure Boating on the Mid-Intertidal Zone,” the best paper Ms. Berron had ever seen from a high school student. She should stareinto the murky water until she saw the rippling edges of a stingray as it fluttered its way along the rocks. That was a reliable thrill: wild animal,you, chance. Contact with an alien world.

She changed into shorts and found her notebook, but she couldn’t help it: she lay back down. She knew what she should have done, but she couldn’t go back to February and do it. That was the problem.

Take, for instance, the morning the doorbell rang. A Saturday. Bright and beautiful.

She’d still been asleep, which was why she hadn’t answered the door right away. She’d called out several times in a not very patient voice, “Could someone please answer the door?” No one had answered her, and the bell rang again. The sofas were empty when she huffed herself out of bed and down the stairs. Sections of the New York Times flung over the kitchen island. Coffee cups drained. A single pancake dry at the edges on a sticky plate. Finally she remembered her sister Ted’s regatta in Alamitos Bay. That was where everyone had gone.

She opened the front door, and there it was: A fortune cookie on a paper plate. Not in a wrapper but under plastic wrap like when you made cookies yourself and gave them to somebody.When she pulled the plastic off, the cookie smelled of almonds. She scanned the giant hedge between her house and Mrs. J’s: nobody there. The Greenbaughs’ magnolia trees: nobody. Nothing but lawns, parked cars, and flickering sun.

A gift or a prank? She didn’t want someone to drive by and see her in her pajamas, so she bent down (careful not to show cleavage), grabbed the plate, and paused. It might be one of those things she heard about all the time but had never personally experienced, proposal bombs; no, it was some made-up word--promposals. Likewhen the guys from the water polo team had painted one letter per bare chest to spell P-R-O-M-? to ask Emily Jenks to go with . . . was it Bruce Greckenthaler? Thisbe forgot which guy, but maybe this was like that. And the cookie could be for Ted. That was a depressing thought. Ted was only fourteen, and guys hit on her all the time. On Valentine’s Day, Mike Rounderman had left roses for her. Red ones. And he was a junior.

Thisbe wanted the fortune cookie to be from Jerome, but that was crazy. Jerome didn’t like her. If he did, he would have smiled back at Thisbe in the quad and picked her to be in his small group when Mr. Shao had asked for volunteers to take the pro-Shylock side.

Thisbe stood there holding the plate. Should she set it back down or take it inside? Say something ironic to the empty street? No, that would be dumb. It was normal to take the plate inside even if it wasn’t for her. She shut the door behind her and then spied through the peephole in case someone made a run for it, but no one did.

The fortune was actually sticking out. Just a bit. And the seam of the cookie was pretty wide. Thisbe could push the fortune back in if it was meant for Ted, and who could blame her for looking, anyway? The plate had no name on it.

She tugged, and the paper slipped free.

TRUST ME, THISBE, it said.

Thisbe, not Ted. The good feeling started small and flared to every corner of the room. It had to be Jerome, because who else would even be worried about whether she trusted him? Two nights earlier, he had come over to study. They had stood together right here, on this very rug. She’d felt bad because of the way the night had ended, with him thinking she thought he was a stoner when she didn’t. She’d smiled at him in the quad the next day and he hadn’t smiled. Or maybe he hadn’t seen her?

TRUST ME.

She’d had no conversations with other guys. Only Jerome.

On the back, under Lucky Numbers, it said: 25 29 66.

The date for prom? Not unless she was going to the prom in the twenty-fifth month of 1966. Maybe they were just random numbers. They probably didn’t mean anything at all.

Awesome, she thought. She took pride in never saying that word, but she thought it now. Because really it was awesome: Jerome Betchman, who was more interesting than Mike Rounderman on every level, was (1) romantic, (2) creative, (3) not mad at her. He’d gone to a lot of trouble to show her that.

She stuck her eye to the peephole again and saw a white car. The sun falling slantwise through the window on her bare feet was even brighter now, and she broke off a tiny piece of cookie to eat. Fortune cookies were the worst dessert in the world, to be honest, worse even than pecan sandies, but this one was sort of buttery, like a crepe, and she had to make herself stop nibbling because she wanted to keep it forever. She took the broken cookie to her room and wrapped it in a tissue and set it in a yellow tin box that said Sunshine State. Then she sat down on her bed to tell Jerome that she got the fortune cookie and she loved it so much and she did trust him. Of course she did! She was sorry she’d ever worried what her mother thought of him. But what should she do? Call him?

No. Her voice would sound too excited. Quavery. She would talk too fast and say too much. If she texted him, though, she could compose it all first. Think it through. Write and revise. Then send.

Thanks for the cookie, she typed.

Did it need an exclamation point? Thanks for the cookie!

Still not that impressive. Thanks for the amazing cookie!!!!!!!

No. Too delirious. Just: Thanks for the cookie!

Should she add an emoji? She didn’t normally use emojis, but Ted said that was why Thisbe always sounded like a cranky old hagball.

Just one. A heart, maybe. Not a red one but a blue one. Or was there a fortune cookie emoji somewhere in her phone? She looked at all the tiny pictures, and although there were a whole bunch of cute ones and a lot of truly weird ones, none of them made sense in this context.

Okay. Just, Thanks for the cookie! and heart picture. Deep breath. Send.

There it went.

She sat expectantly for five minutes. Nothing happened. The sun shone. Wind clattered through a palm frond. A bird sang.

She would take a shower and then see if she got a message.

Nothing. Not at 12:30, 1:30, 2:30, 3.

As the hours passed, she did an outline for history, a Spanish assignment, and all of her calc. Practiced the piano. Ate not one but two muffins. The only message she received was from Ted. Bullet in the third race!

Bullet as in first place.

Congrats! She typed. The day was eight million years long. All the sunshine was going to waste, but she couldn’t think what to do with it. If Jerome had left the cookie for her--if anyone had, really!--he or the random stranger would be wondering if she got it, right? Wondering what she thought. Waiting to hear back from her. But clearly Jerome wasn’t.

The answer she was waiting for finally came after dark. Two stony words.

All that Jerome said was, What cookie?

She waited a few minutes so it wouldn’t seem like she was one of those people who constantly checked their phone. She felt so confused and deflated now. Prickly all over her skin and in her stomach. Something was wrong, obviously. She typed: The fortune cookie.

Sorry. Wasn’t me.

It wasn’t? Oh. Okay! My mistake. No heart shape or koala bear or smiley face. There was no emoji for this.

The conversation ended. Sat there like a dead thing. No matter how many times she reread it, she couldn’t find any desire on Jerome’s part to talk with her. She’d gotten a cookie from someone, and the cookie wasn’t from him. Of course he would be terse.

But who had sent thecookie? And why? She opened the tin box and picked up the curved shards shehadn’t eaten. She bit off another piece and tasted it as if the flavor might provide a clue. It wasn’t quite as delicious now. She turned the message over again and read Lucky Numbers 25 29 66. There was nothing lucky about them, as far as she could see.

The next fortune cookie appeared in her backpack after lunch on Monday, in the front pocket where she kept her pencils. Jerome was in class as usual, sitting slightly behind her and far to the right. Thisbe stared at the cookie briefly and left it there, straightening herself in the chair. If she unwrapped the cookie on her desk or even in her lap, everyone near her was going to notice, including Jerome and Mr. Shao. She glanced around to see if anyone was watching her lean back down for the second time to take a pencil out of her bag. Jerome wasn’t looking right at her, but he seemed to be aware of her self-consciousness, so she turned back to Mr. Shao and listened to the difference between metonymy andsynecdoche.

She would have to wait. All through class. She waited and she thought about the cookie wrapped in plastic.

It seemed weird to go to a bathroom stall to unwrap something you might eat, but that’s what she did after the bell. Peeled the plastic, broke the cookie open, and slid the paper out. It had the exact same lucky numbers on the back—25 29 66—so they must mean something. And this time the fortune said: YOU ARE SO MYSTERIOUS.

What was she supposed to make of that?

She didn’t eat any of it. She was in the bathroom, first of all, and that would be gross. She wrapped the broken halves and tucked them in her backpack and felt distracted the wholerest of the school day, wondering if she was missing something, if someone was watching her.

She stayed after school to make up a physics lab, so it was nearly 3:30 when she went to her bike. Only a few people were walking around when she reached for her helmet and saw it, another cookie, right there in her basket. She froze. A girl in a purple jacket, Wendy something, was walking slowly, so slowly to the gym. Thisbe waited, fiddling with her lock. No one else was nearby. The windows of the classrooms were tinted, so she couldn’t see anything in them but reflected palm trees and brick walls. Finally she just picked up the cookie like it was a normal thing and untwisted the plastic and pulled out the fortune.

PLEASURE AWAITS YOU BY THE SEA, it said. Same lucky numbers.

Corny, but in a good way?

No one appeared at aschool window. No one stood by a car in the parking lot, waiting for her. The two boys walking with their lacrosse sticks barely noticed her. And yet, riding away from the school, she felt strangely good, as if the messages meant something had changed about her.

Every day that week she reached into her backpack with a little knot of hope in her stomach and looked into her bicycle basket the way you looked under bushes during an Easter egg hunt. Nothing on Tuesday. Nothing on Wednesday. Nothing on Thursday. On Friday she went to her bike at the usual time after school, in a crush of people, and finally, finally there it was: a pale, curved cookie in plastic. She blushed. She couldn’t help looking around. People were talking to one another in the usual way. Didn’t they see it? A girl from Spanish said hello, but Thisbe didn’t move to point out or pick up the cookie because they didn’t know each other all that well. She extracted her bicycle in a haze, waited for more space to open up behind her, rolled backward and then forward. She couldn’t wait any more, so she picked up the cookie, studied it self-consciously, and stuck it in her pocket. No one said, What’s that?

Perhaps Clay had been watching from a distance, though, because by the time she’d crossed Orange Avenue and was riding along Seventh Street by the park, he was there. On a bike. Beside her. Jerome’s best friend, and surreally handsome. She couldn’t even look straight at him without blushing.

“Aren’t you going to open it?” he said.

“What?” she said.

“You should open it.”

“Why?”

“Because you might want to answer me.”

“Okay,” she said, though that wasn’t what she’d meant to say. She wondered if he meant for her to stop right then, in the street, at the corner where the Catholic kids were standing around in their red shirts and their parents were waiting in a line of shiny idling cars.

“Maybe I will,” she said, and she kept riding slowly along. He stayed beside her for another block before he said, “You’re killing me.”

“Oh, yeah?”

“Yes. The suspense.”

“I turn here,” she said. She stopped her bicycle, and he stopped his.

“So maybe you should open it now.”

“All right.” Again, that wasn’t what she wanted to say. She needed more time to think. Clay Moorehead had asked her to trust him? Clay Moorehead had sent her a message informing her that pleasure awaited her by the sea? Not love or romance, but pleasure?

She slowly peeled off the sticky plastic. She tried to remember that she was not a bimbo and she didn’t need his approval. The kind of thing her mother always tried to tell her when Thisbe’s feelings were hurt.

“So do you have a fortune cookie machine at home or what?” she asked. It was hard to breathe because everything was strange. The sky was extra high up and the trees were in sharp focus. She wished she weren’t wearing her dorky bike helmet.

“No.”

“Do you order them from somewhere?”

“No. I make them. Someone else bakes them and I write the messages.”

“Who’s the someone?” she asked. She had it all unwrapped now and held the sweet, sticky curve of it in her hand.

“Lourdes.”

She raised her eyebrows. People kept streaming past them in cars and on bikes, students from the high school most of them, but none of them, thank God, were Jerome.

“Oh,” Clay said vaguely, as if he was embarrassed, “she cooks for all of us.”