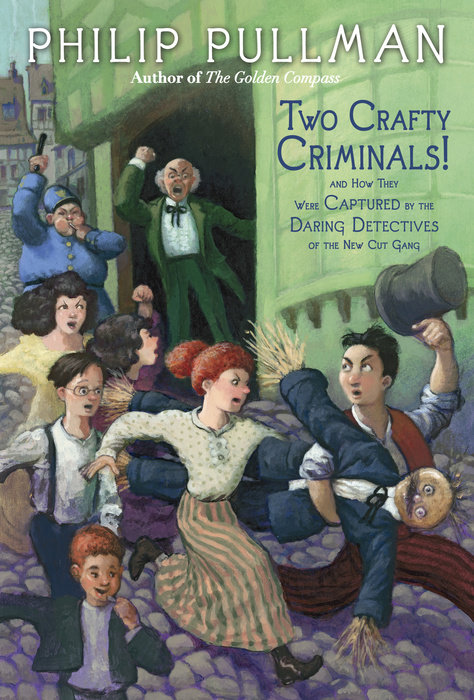

Two Crafty Criminals!

Benny Kaminsky and Thunderbolt Dobney lead a rag-tag gang of neighborhood rowdies. Their territory is the New Cut on London's South Bank--a place bristling with swindlers, bookies, pickpockets, and the occasional policeman. And their aim is to solve crimes.

When counterfeit coins start showing up in their neighborhood, Thunderbolt fears his own father may be behind the crime. But his friends devise a way to trap the real culprit. Then the gang takes on the case of some stolen silver. They have just two clues--a blob of wax, and an unusually long match. But even this slippery thief is unmasked by the determined kids of the New Cut Gang.

Filled with silly sleuthing, improbable disguises, crazy ruses, and merry mayhem, these stories are action-packed romps from one of the best storytellers ever--Philip Pullman.

An Excerpt fromTwo Crafty Criminals!

One

Dippy’s Ambition

Lambeth, London, 1894

The criminal career of Thunderbolt Dobney began on a foggy November evening outside the Waxwork Museum. Thunderbolt had never thought of himself as a criminal; he was a mild and scholarly youth. But he was a passionate collector of curiosities, and for some days now he had been filled with desire for the odd-shaped lump of lead belonging to Harry Fitchett, a boy in his class. Finally, after much bargaining, he had persuaded Harry to swap it for a length of slingshot rubber.

The exchange took place under a hissing gaslight by the Waxworks entrance.

“This is stolen property, this lead,” said Harry. “It come off that old statue of King Neptune outside the Lamb and Flag. You remember.”

The knowledge that he was holding a piece of criminal history added to Thunderbolt’s pride. Harry ran off, twanging his length of rubber at the legs of passersby, and Thunderbolt dropped the lead into his pocket with a guilty thrill.

The others, meanwhile, were gazing up at the poster advertising the latest attraction at the Waxworks.

“A Victim of the Atrocious Death of a Thousand Cuts,” read Benny Kaminsky.

Benny was a stocky, dark-haired boy of eleven. When you saw Benny at first, you took him for an ordinary boy. When you’d known him for half an hour, you were convinced he was a genius. When you’d known him for a day, you suspected he was the Devil, but by then it was too late: you were drawn in. Everyone who knew Benny was drawn in, because he was less like a boy than a whirlpool. The New Cut Gang were proud to follow him.

Thunderbolt peered at the poster Benny was looking at.

“Ah! I read about that in the encyclopedia,” he said. “What they do is, they tie ’em up and slice bits off ’em with a razor. They start at the feet and work up. Takes hours,” he added enthusiastically, pushing his glasses up with a grimy finger.

“Well?” said Bridie. “Are we going in or not?”

Bridie Malone was red-haired and red-tempered, and at least as fierce as Benny. Everywhere that Bridie went, her little brother Sharky Bob came too. He was a placid and benevolent child who would eat anything, and often did. The others didn’t mind having Sharky about, because they’d often won bets on his ability to chew up and swallow dog biscuits, champagne corks, fish heads, and anything else the sporting citizens of Lambeth offered him.

He was plucking at Bridie’s sleeve now.

“Dippy’s selling chestnuts,” he said. “I seen him just now. I likes chestnuts,” he added helpfully.

So did they all. The Death of a Thousand Cuts forgotten, they streamed across the road and around the corner to Rummage’s Emporium, where Dippy Hitchcock had set up his hot-chestnut stand. Rummage’s Emporium took up several shopfronts. It was the biggest store in Lambeth, and the windows were blazing with light and streaming with condensation. Old Dippy was selling some chestnuts to a customer who’d just come out, and he greeted the kids cheerfully.

“Three penn’orth, please, Dippy,” said Benny.

He had earned a shilling earlier that day by holding some horses for the Thompson Brothers (Removals, Funerals, and Seaside Excursions). You got sixteen chestnuts for a penny, so that would mean twelve each. The kids stood around Dippy’s little stove to eat them, fishing the smoking nuts out of the triangular twists of paper and rolling them between their palms to loosen the skin.

“You been to the Waxworks, then?” said Dippy. “I’d like to be a waxwork.”

“They don’t make waxworks of hot-chestnut men,” said Thunderbolt. “Only Kings and criminals and people like that.”

“I used to be a criminal,” said Dippy. “I set out to be a pickpocket. But I had to give it up on account of me conscience.”

“Unless you’re a celebrated murderer, it’s not worth mentioning crime,” said Benny. “Ain’t you done anything else to make you famous, Dippy?”

Dippy rubbed his bristly jaw. “No,” he said mournfully. “But I’d love to be a waxwork. Make me feel me life had been worthwhile, somehow.”

Another customer came out of Rummage’s and bought a pennyworth of chestnuts, paying with a sixpence. Bridie was interested in this waxwork talk, but even more interested in the nearest window, where a stout and shiny man called Mr. Paget, the Gentlemen’s Outfitting Manager, was clambering about, arranging a mannequin. Every time he lifted the arm into position and turned round to pick up some gloves from behind him, the arm fell down again, and he got more and more vexed and more and more shiny. The arm came up--the arm fell down; he dropped the gloves; the dummy swung forward and butted him on the nose; he said (very visibly) a wicked word, and looked guiltily out at the pair of wide blue eyes watching him. Bridie turned at once to a kindly old gentleman passing by and asked him what the word meant, pointing at Mr. Paget.

“No! No!” Mr. Paget mouthed in horror, and waved his hands, but then had to lurch sideways to catch the dummy, and knocked over a chair; which was the point when Mr. Rummage stormed out of the main entrance.

“Get away from that window!” he bellowed, shaking his fists. “I will not have vagrants and costermongers on my property! I’ll have the law on you! Smoking up my windows and leaving your filthy rubbish on the pavement! Get away! Go on! Hook it!”

Dippy didn’t want to move, because standing in the bright light of the window among the crowds going in and out of the shop was good for business; but Mr. Rummage was a roaring, red-faced bully, and no one could stand up to his shouting for long. So the gang helped Dippy to move and set up a little further away, and Mr. Rummage scowled and strutted back inside.

“Great bellowing bag of wind,” said Bridie.

“I’d like to get me revenge on him,” scowled Benny.

The gang had taken a dim view of Mr. Rummage since the time he’d run them out of the shop for offering to demonstrate the camping equipment. It was Benny’s idea. They’d offered to pitch a tent inside the store, and cook meals on a “Vesuvius” Patent Folding Stove, and filter water with an “Anti-Buggo” Microbial Filter, and sleep in the “Kumfi-Snooze” Patent Sleeping Valise, and they’d even put on a display of Apache war dancing to entertain the customers. Benny was very proud of this plan. Like many of his ideas, this one had spun out of control, and he imagined a Corps of Demonstrators---highly skilled and efficiently trained kids, say about ten thousand of them to start with--who’d be paid by grateful shop-keepers throughout the kingdom to show customers how to use the goods on sale. Benny would take a small percentage, say about seventy-five percent, and within a year he’d be rich, have branches in America, float the company on the Stock Exchange, stand for Parliament, et cetera, et cetera.

Anyway, he was explaining to Mr. Rummage how useful it would be when Thunderbolt had that accident with the “Luxuriosum” Folding Umbrella Tent, and then the Peretti twins got carried away in the “Pegasus” Self-Propelled Invalid Chair, and Sharky Bob discovered the “Surprise” Officers’ Dried Food Ration Tin, and things got out of control. Mr. Rummage had thrown them all out bodily and forbidden them to enter the store ever again.

“Here, Dippy,” said Benny, “where’s me change?”

“Oh, sorry,” said Dippy. “You give me a shilling, didn’t yer? Here’s a threepenny bit and a nice new tanner.”

Benny took it, but looked at it oddly and bit it.

“Here, Dippy,” he said, “this is snide, this is. Where’d you get it from?”

He held it out. It was new and shiny, and there was Queen Victoria and all the letters around the edge, and there was a toothmark right across Her Majesty’s nose.

“It’s snide, all right,” said Bridie. “Look, Dippy, it ain’t a proper sixpence at all!”

They all crowded close. Dippy took the coin and tested it with his four remaining teeth.

“Yeah, I reckon you’re right,” he said, baffled. “It’s a fake, and no error. Wonder who passed that on me? Here, you better have some proper money.”

He didn’t have another sixpence, so he gave Benny six ordinary pennies, and looked at the snide sixpence with disgust. Thunderbolt could see something else in his expression, too. A sixpence was a lot of money when you only made two or three shillings a day.

But then an old lady came along and bought some chestnuts for her granddaughter, and then Johnny Hopkins came out of the Welsh Harp, wiping his whiskers, and bought some too, and the gang said goodbye to Dippy and wandered off.

“It’s not fair,” Bridie said when they reached the Waxworks. “Whoever gave Dippy that snide sixpence knew they were cheating.”

“It’s not fair not letting him be a waxwork either,” Benny said. “All them waxworks in the Museum, all they done was murder people and discover America and be Kings and Queens and that. Where’s the justice in that? I bet if Dippy was a victim of the Death of a Thousand Cuts, they’d put him in, all right.”

“There’s not enough of Dippy to make a thousand bits,” said Bridie.

Benny scowled at the closed door of the Waxwork Museum.

“We’ll get Dippy in there if it’s the last thing we do,” he said.

When Benny’s expression was set like that, the rest of the gang knew better than to argue with him. The others left him there, frowning Napoleonically, and walked home towards Clayton Terrace.

“I wouldn’t mind putting one over that Professor who owns the Waxworks,” said Bridie. “He slung me and Sharky out last July.”

“I bet I can guess why,” said Thunderbolt.

“Well, it was only a little finger off one of the blokes being tortured in the Chamber of Horrors, and he’d lost a lot more than that already. Ye’d hardly notice.”

“What did it taste like, Sharky?”

“Nice,” said Sharky Bob stolidly.

“And the Professor made us pay for it, and I had a threepenny bit, and he took it all. I bet that’s enough for a whole arm.”

They walked on through the gathering mist, which was making the gaslights look like dandelion heads.

“I hope Dippy doesn’t get another snide sixpence,” said Thunderbolt.

“Ma got one in the butcher’s yesterday,” said Bridie. “Ye should have heard her cursing. Hey, is that yer pa down there?”

They were outside Number Fifteen, where Thunderbolt and his pa lived on the ground floor and Bridie and the rest of her large family lived upstairs. Bridie was peering down into the “area,” the little space in front of the basement window, where an eerie glow was flickering through the grimy window onto the damp bricks.

“Yeah,” said Thunderbolt. “He’s making something new. I dunno what it is, ’cause it’s a trade secret.”

Mr. Dobney was in the novelty-and-fancy-gifts trade. He made candlesticks that looked like dragons, pipe-cleaner dispensers that looked like dog kennels, soda-water-bottle holders that swiveled round on a turntable, and all kinds of ingenious devices. His latest line was a combined glove holder and dog whistle, but for some reason there was no demand for them, and they hadn’t sold at all. So he’d rented the basement specially and started making a new line, only Thunderbolt wasn’t allowed to know what it was. All he did know was that it involved electricity: Pa had lugged a lot of heavy batteries and coils of wire down there, and occasional flashes and electrical humming sounds came out from behind the closed door.

“I better get in,” said Thunderbolt. “Put his tea on.”

“I likes tea,” said Sharky Bob. “I likes biscuits and all.”

“Yeah, Sharky, we know,” said Bridie. “What ye got for yer tea, then?”

“A couple of herrings,” said Thunderbolt.

“How ye going to cook ’em?”

“Dunno. Boil ’em, I suppose. They’re only a kind of kipper, and you boil kippers.”

Bridie shook her head in exasperation. “I better show ye.”

Thunderbolt had been looking after his pa for nearly a year now, and Mr. Dobney had never complained yet. Thunderbolt felt a bit put out by Bridie’s contempt for his cooking, but he let her storm into the kitchen and bang about till she found the frying pan. She was about to put it on the range when she recoiled, and held it under the lamplight to look more closely.

“What in the world’ve ye been cooking in this?” she said, picking disgustedly at some tarlike substance on the bottom.

“Toffee, I think,” said Thunderbolt, trying to remember. “That was when Pa thought of going into the toffee-apple trade and he was trying to find a cheap way of making toffee. He used fish oil instead of butter, only it didn’t set properly . . .”

Bridie put down the frying pan and found a skillet. “This’ll do,” she said. “Give us the herrings and a knife and find me some salt.”

She slid the knife deftly up and down and scraped out some fascinating strings and blobs of fish innards. Sharky Bob stopped licking the frying pan and reached for them automatically, and she slapped his hand away.

“Right, now what ye do is make the skillet hot and scatter it with a big spoon of salt and lay the fishes on it. They’re oily enough to sizzle by theirselves without any grease. What’re ye reading?”

She laid the herrings where Sharky couldn’t reach them, tucked a strand of curly red hair behind her ear, and peered at the open books on the table.

“Me homework,” Thunderbolt explained. “We got to copy out and learn ten words out the dictionary, together with what they mean.”

“Aardvark,” read Bridie. “An edentate insectivorous quadruped. Well, that’s helpful, I’m sure. Ambergris: fatty substance of a marmoriform or striated appearance exuded from the intestines of the sperm whale, and highly esteemed by perfumers. Yuchh. Asbestos: a fine fibrous amphibole of chrysotile, capable of incombustibility . . . What in the world does all that mean?”

“Oh, we don’t have to know what it means. Only what it says.”

“And that’s what ye get up to in school? Catch me going,” said Bridie, removing the frying pan from Sharky Bob. “Come on, Shark, time to go. Bye, Thunderbolt.”

Thunderbolt said goodbye, stirred up the fire and put another few lumps of coal on it, brought the lamp to the table, and sat down to finish his homework.