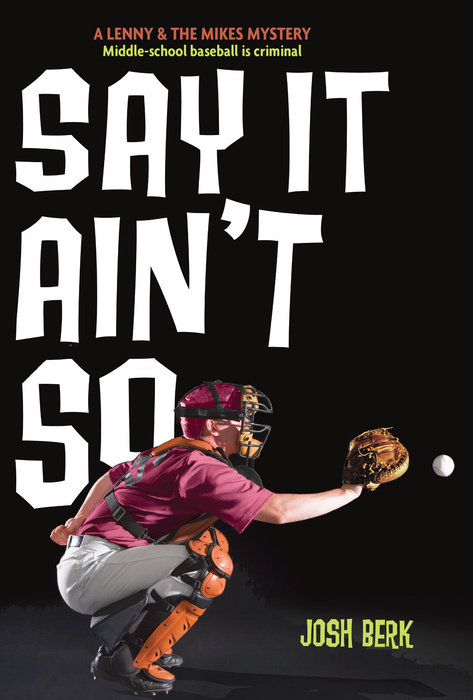

Say It Ain't So

Say It Ain't So is a part of the Lenny & the Mikes collection.

Lenny, Mike, and Other Mike are back in school for the glory that is seventh grade, and this year, Mike is determined to make catcher on the middle-school team. When Mike's hard work pays off and he wins the coveted postition, Lenny is a little jealous, but he'll settle for being the team's unofficial announcer.

The team has a brilliant new pitcher, Hunter Ashwell, and though he's a bit of a jerk, he and Mike have a great pitcher/catcher dynamic that could make the team champions. But things take a strange turn when Hunter's perfect pitching streak goes downhill, and Lenny suspects foul play—specifically, someone stealing Mike's catcher signals. But who could be responsible, and why?

An Excerpt fromSay It Ain't So

CHAPTER ONE

I could tell it was going to be a good year when Mike called me up on New Year’s Day and asked me to kick him in the crotch. I’m sorry--did I say “good year”? I meant “sorta-terrible-really-bad-then-kind-of-cool-but-mostly-just-weird year.” I guess you could simply say it was going to be an interesting year.

Last year ended on a bad note, so I should have predicted weirdness. The holidays around the Norbeck house were just awful. My parents (mostly Mom) got it into their heads that we shouldn’t celebrate Hanukkah or Christmas. My dad is Jewish and my mom is Christian, so usually we’d celebrate both. I was always pretty pleased with this arrangement, as you can imagine. It meant the old eight days of gifts during Hanukkah and still a pretty sweet Christmas haul. Presents galore! Trees and menorahs! Candy canes and potato pancakes! Actually, I don’t really like potato pancakes. And candy canes always start out exciting but end up being disappointing. They’re basically just a sticky mess you’re sick of before you’re even halfway done. But that’s beside the point. The point is, every December for the first twelve years of my young life was awesome.

Not this one.

This year, Mom said, we’d still celebrate the spirit of those holidays, but when it came to gift getting, we’d celebrate zilch. I’m not kidding! Zero! Zip! Nada! She had it in her head that I had way too many toys and things. So her brilliant idea was that instead of Christmas or Hanukkah, we’d celebrate Discardia. Yeah, I had never heard of it either. It’s a made‑up holiday. And okay, maybe all the holidays are made‑up holidays if you think about it. Ever look at one of those calendars that has every holiday on it? There are some weird ones. Grandparents Day? Administrative Professionals Week? National Mustard Day? (That’s actually a pretty good one that I look forward to every year.)

But seriously, sports fans, I would have much preferred celebrating Principals Day for a whole month to the travesty that is Discardia. . . . (Yeah, Principals Day is also a real one. I wonder who made that up. . . .)

Picture me waking up on the morning of December 25. The room is not packed to the gills with presents. There are no stockings hung by the chimney with care. There are no halls decked with boughs of holly. No fa! No la! No la-la-la-la-la-la‑la! Instead, by the tree there is an empty wheelbarrow. This would be bad enough if the wheelbarrow were your only gift. (Unless you were some sort of ’barrow collector and the wheelbarrow was the last one you needed for your ’barrow collection.) But no, not in the Norbeck house. During Discardia the wheelbarrow is there to steal your toys. To cart away your happiness like some sort of Grinch on wheels. (Grinch on wheel, I guess.)

On the morning of Discardia you glumly fill up this wheelbarrow with your favorite toys. Okay, at first it’s not your favorites. At first it’s the oldest and worst toys you’re not even sure why you still own. It’s the broken trucks, the outdated video games, the superhero action figures missing one or both legs. A puzzle of the Rocky Mountains you lost, like, ninety pieces to and you never really liked doing anyway. Books you are more than glad to get out of reading. But no, these things will not make your mother happy. She will invite you to “dig deeper.” To “truly give.” To “give until it hurts.” You respond that it already hurts, even though you should know better than to say anything. Because any time you say anything, Mom just launches into another speech.

“Lenny, don’t you know that others have nothing? Nothing at all! Others would be happy with just a warm meal. Others would be thrilled just to have a roof over their heads. Others would appreciate things.”

“Hey,” you say. “If others are so easy to please, then they’re sure going to love this Spider-Man head! I have no idea where the body is.”

When will you learn? Why do you say things like this? Because the response is just more speeches.

“Lenny, I am truly disappointed in you. You have a chance to make yourself a better person this Christmas season. Isn’t that the greatest gift of all? You have the chance to make yourself a better person and the chance to brighten the life of some poor kid who has nothing, and you’re going to make jokes? You’re going to throw a fit that you don’t have the new baseball game for the video-game machine?”

You want to point out that you already do have the new baseball game and that no one says “video-game machine,” but by now you’ve learned your lesson. You want to point to the new car in the driveway and ask Mom when she plans on giving that away. You want to point to the jewelry around her neck and the rings on her fingers. But you don’t. You know that saying this would be a terrible idea. You know that saying this would probably make said baseball game end up in the wheelbarrow. So you shut your mouth and bite your tongue.

You give till it hurts.

Then you give some more.

CHAPTER TWO

By the end of the holiday break I was pretty bummed and (gasp!) feeling ready to go back to school. It was awful hanging around the house, thinking about everyone else’s presents. Pennsylvania winters are cold and wet and icy. This whole December had been mostly just slush--not even a snowfall decent enough to chuck snowballs or bust out the sled.

Too wet to go out, and too cold to play ball. That’s me quoting Dr. Seuss. Shut up, I know it’s a baby book, but it’s stuck in my head because Dad used to read it to me nine million times. I still have my copy with a homemade bookplate reading LENNY’S FAVORITE BOOK pasted inside. Only, favorite is spelled wrong. Come to think of it, so is book. And let’s be honest, the odds are beyond pretty good that I put five extra Ns in Lenny’s. LNNNNNNNY’S FAVRETE BOK. Whatever. I was, like, four.

Also, every year around the first of January I start to get jittery from not having baseball to watch. This year was especially rough since the Phillies flamed out in the first round of the play-offs. The off-season was long and cold and as black as a starless night.

I will say that seventh grade at Schwenkfelder Middle School was shaping up to be quite a bit nicer than sixth. Me and my best friends (Mike and Other Mike) were sort of legends of the seventh grade. I mean, not everyone cared, but we did get somewhat famous the previous summer. How? Oh, only by solving the biggest crime in Philadelphia Phillies history. Part of the chase for a murderer (which eventually led us into the line of fire and also the Phillies dugout) introduced to us our favorite player, catcher Ramon Famosa. Of course, that turned out not to be his real name. And when I say “our favorite player,” I mainly mean me and Mike. Other Mike has no interest in baseball. He’s mainly into books about wizards--sorry, warlocks. There is an important distinction that escapes me, but Other Mike would be really happy to tell you all about it and probably make a presentation that would last a few hours.

The point is that something kinda major happened when we met Ramon Famosa, something besides almost getting killed in a shopping mall. Famosa saw Mike grab a video camera out of the air and block a sprinting little person from stealing it. It was a pretty awesome move by Mike, I thought. Famosa agreed. He told Mike that he should be a catcher. Now, when a big-league catcher tells you that you have the right stuff to be a catcher yourself, you’re going to think about it. Ramon Famosa telling you that you could be a catcher is like Leonardo da Vinci telling you to go pick up a paintbrush. Which would be really impressive on account of da Vinci being dead. But I can’t think of any painter who is alive, so just go with me here. The only problem with that whole idea is that there’s a reason Mike quit baseball. His arm. Mike was a pretty good pitcher when we were about nine. That was the same year that I quit due to a highly embarrassing reason that I don’t want to mention again if I don’t have to. But Mike quit due to his arm injury.

Mike is sort of a stubborn personality, so he didn’t listen to any of the repeated warnings from his coaches about resting his arm. He’d pitch the maximum number of pitches allowed in Little League and then go home and throw a million more fast ones into the pitching screen in the backyard. His shoulder got pretty bad and he had to take a break from pitching. He could have played a different position and stayed on the team, but like I said: Mike is pretty stubborn. He had it in his mind that he’d be a pitcher or nothing, and so nothing it was.

Let me say that part of me thought that maybe he was also quitting baseball to be a good friend to me. My career was definitely over, so maybe he was quitting out of solidarity? Yeah, right.

CHAPTER THREE

On New Year’s Day, as I left our house and rode my bike to Mike’s house, it had (finally!) just started to snow. Not enough to stick to the ground and extend winter vacation, which would have ruled, but enough to dust the grass and stick in everyone’s hair. The flakes landed like dandruff in my black hair as I finished the short ride, parked my bike in the driveway, and rang the doorbell at Mike’s house.

Mike’s mom answered the door. She was carrying a basket of laundry on her hip. “How many times have I told you that you don’t have to ring the doorbell?” she asked. “You’re like family.”

“Thanks,” I said. “I always forget. The cardiologists trained me to be polite, I guess.”

“It’s weird that you call your parents ‘the cardiologists,’ ” she said as I came in the front door and took off my boots. I just shrugged.

“Mike around?” I asked. It was a dumb question because I knew that he was.

“Garage,” she said. “It’s freezing, but he’s been out there all morning hitting off the tee.” I heard a thwack of bat against ball as if to prove her point.

“I guess now he wants to work on his defense,” I said.

“Don’t tell me that you’re here to help him test out his cup,” she said.

“Ha‑ha,” I said. “Yeah. How did you know?”

“He asked me to kick him in the crotch this morning. I told him there are just some limits to a mother’s love. His sister volunteered, but I thought that wasn’t the best idea.”

“Yeah, there’s a pretty good chance that would have ended badly,” I agreed.

The thwack sounds from the garage stopped, and a second later Mike walked into the foyer. It might have been an optical illusion, but he seemed bigger than the last time I saw him, which was just the other day. He was filling up almost the whole doorway. He was sweating despite the cold and breathing a little heavily.

“Hey, Len,” he said. “You might want to look into using that bottle of Head & Shoulders I gave you for Hanukkah.”

“Huh?” I said.

“Your hair.” He pointed with the batter’s glove on his left hand. “Snow makes it look like you got dandruff.”

“Oh yeah,” I said. “I was just thinking that.” I took off my coat and hung it on the rack by the door. Mike’s house always had a great smell and a lot of snacks. It was hard not to be in a good mood when you walked in the door, no matter how bizarre a mission you were on.

“Weird thing is, I wish I would have gotten a bottle of dandruff shampoo for Hanukkah,” I said. “Better than nothing.”

“Better than having to give away stuff,” he said. “I still can’t believe that.”

“Yeah, but, you know, it’s making me a better person and all that.”

“Do you feel like a better person?”

“Oh yeah,” I said. “I feel like the greatest person in the world. I feel like if Martin Luther King Jr. and Mother Teresa had a baby.”

“But you’d trade it all to get your video games back?”

“Ha‑ha, yeah. Trade it in a heartbeat.”

“Mother Teresa would be proud,” he said. “Listen, I have to go get the cup. You head into the garage. I’ll meet you in there in a sec.”

I headed into the garage. It was packed to the gills with empty boxes that had held the toys Mike and his little sister, Arianna, had gotten for Christmas. I tried not to be jealous. There was also a spot in the garage where Mike had cleared away the boxes, garbage cans, old shoes, and other random junk that always fills everyone’s garages. He had turned this area into his little catcher-training gym. He apparently was taking it very seriously. There was a catcher’s mitt, of course, and some balls, as well as dumbbells and even a book from the library on how to be a catcher.

It was a really old book. Maybe it was the only book they had in at the time, or maybe Mike’s dad was remembering it from his childhood and checked it out. Johnny Bench was on the cover, and the title was Hey You! Be a Better Ballplayer! Become a Star Catcher! Apparently, “Be a Better Ballplayer!” was a whole series. Also, apparently, the author really! liked! exclamation! points! The 1970s were a pretty exciting time, I guess. Sideburns!

Mike was taking a long time getting his cup on. I suppose it’s a pretty delicate procedure. I’ve never worn one myself and don’t fancy that I ever will, thank you very much. I skimmed most of Hey You! Be a Better Ballplayer! Become a Star Catcher! and it was not really worthy of such exciting punctuation, I can tell you that. It had lots of the basics about how to crouch and call pitches. A riveting chapter on footwork. A bunch about how to throw. We can only assume that Mike skipped over the throwing sections and just hoped somehow that wouldn’t be a major part of his game. I guess he could throw out a runner if he had to--it was the repetitive stress of pitching that was messing up his shoulder.