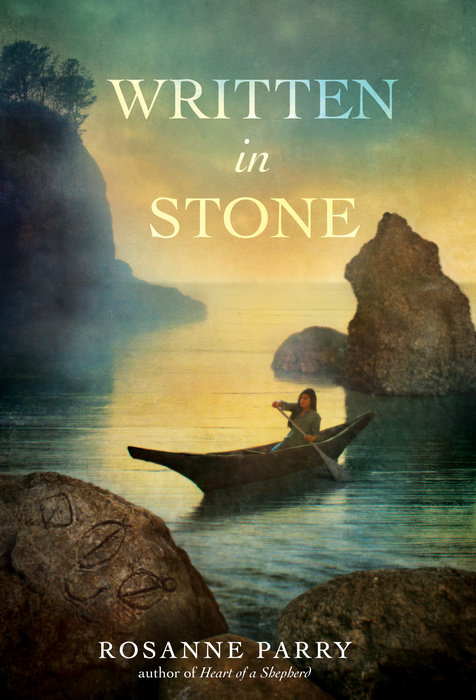

Written in Stone

Rosanne Parry, acclaimed author of A Wolf Called Wander and Heart of a Shepherd, shines a light on Native American tribes of the Pacific Northwest in the 1920s, a time of critical cultural upheaval.

Pearl has always dreamed of hunting whales, just like her father. Of taking to the sea in their eight-man canoe, standing at the prow with a harpoon, and waiting for a whale to lift its barnacle-speckled head as it offers its life for the life of the tribe. But now that can never be. Pearl's father was lost on the last hunt, and the whales hide from the great steam-powered ships carrying harpoon cannons, which harvest not one but dozens of whales from the ocean. With the whales gone, Pearl's people, the Makah, struggle to survive as Pearl searches for ways to preserve their stories and skills.

An Excerpt fromWritten in Stone

1

Waiting for the Whale

I should have been praying that spring day. I should have been fasting for a successful whale hunt, but I was running. I ran along the wet sand with a harpoon in hand. The gray whale raised up his barnacle-speckled head, and raised it again to offer his life for the life of the tribe. I planted my feet and hurled the harpoon.

Thunk! My stick hit the log dead center and splashed into the sea.

I shouted in triumph and stamped my bare feet at the edge of the waves. A dozen steps into the whale dance, I froze. Dancing was forbidden during a whale hunt, and singing too. My father depended on it. I imagined him standing at the bow of the whaling canoe while my uncle and cousins paddled. He would hold his harpoon ready. The round cedar bark hat would shade his weather-lined eyes: my papa, Victor Carver, the best whaler of the Makah, probably the best Indian whaler on the whole Pacific coast.

He would find us a whale, find one when no one else could. I pictured him leaping and striking and pulling the cedar rope. No depth or speed or strength would outlast him. He would bring home thousands of pounds of meat and hundreds of barrels of oil to feed our village and light our lamps. Sea captains knew his name and anchored off our shore to buy oil for cash money.

I looked over my shoulder. Behind me was my village; its arc of homes, boats, totem poles, and fish racks was pressed in the narrow place between waves and cedars. Only one house was traditional, with long cedar planks; the others had shingles and windows. But old or brand-new, every front door faced the ocean.

My grandfather’s house was the best in the village. Our Whale crest in red and black paint covered the wall on the north side of the door, and our Raven crest covered the south. Totem poles marked the corners and doorways of our home. Everyone else lived in tiny matching houses with glass windows and the same color siding. But I was a princess. My father and grandfather were Makah whalers, and my mother was a Tlingit princess from the northern tribes, a weaver of the famous Chilkat blankets. We kept the traditions, the old stories, songs, and dances.

I saw my grandma coming down the beach toward me. Her limp made her roll when she walked, like a bear with a belly full of salmon. She was a Quinault from the south, married into the Makah as my mother had married in from the north. Sometimes I thought I was her favorite grandchild, but I was never sure. She had a bear’s temper. I brushed sand off my hands and waited.

“Never turn your back on the ocean, Pearl. What if it decided to roll your whale up there with the other beach logs?”

She tilted her head in the direction of the great pile of twisted driftwood at the top of the beach. They were bleached white and worn smooth from sun and salt. I shrugged and turned away from her, wondering if she had seen me doing a man’s dance.

“Walk with me,” she said. “The tide’s turned, and Charlie’s waiting for you at the watching place.” We turned our faces north, and I schooled my steps to match hers.

“Have there ever been women whalers?” I blurted out.

“Never,” she said without pause. She put a calloused hand on my shoulder and leaned for a moment to rest her injured foot. “A woman’s work is hard enough. Why are you borrowing burdens?”

“Women did plenty of men’s work during the war, at the mills and the cannery and on the railroad. I could be a great whaler.”

Grandma turned to me, her face a closed shell. “That war was poison to us, and nothing good came of it. We should divide work the way we always have.”

I kicked at the sand. “Why don’t I get to have adventures?”

“Shush! Shush your complaining, Pearl. We are waiting for a whale. We set aside our quarrels. We strive to be worthy.”

“But it’s not fair!”

“It’s not lucky. Not respectful. We need this whale; you know we do. Now climb up that lookout. Charlie’s been up there for hours.” Grandma pressed a bundle of smoked salmon wrapped in a maple leaf into my hand. “And mind your quelans.”

I trudged down the beach to the spit of sand and small rocky tide pools that connected the sea stack to the shore. At high tide, the rugged thumb of rock would be an island, but now I could walk across the sand without getting wet and climb the trail, as steep as a ladder, to the spot a hundred feet over the water where we watched the ocean.

My cousin Charlie looked up when I reached the top. I could tell he was relieved to be done with his hours of sitting still, doing nothing but looking at the water. Charlie was born the same month as me, and we were equal back to back but he wanted to be taller than me. His father was the navigator. His brother, only seventeen, was already a whaler. Charlie was Grandpa’s favorite, a drummer. Someday he would be a great singer.

But I was taller, because my father was the harpooner, the leader of the whalers, and Charlie knew it. He tried to tease me with mimes of the animals he’d seen while he was watching. He wanted me to scold him or laugh or do some other dishonorable thing at the watching place while the whalers were out. I gave his hair a yank and nudged him toward the beach. He walked away with a waddle in his step like Charlie Chaplin at the movies. Grandpa may have thought that Charlie would grow up to keep all his sacred songs, but I knew he really wanted to be a jazz singer, a movie star, a hunter of applause. No wonder the whalers didn’t return while he was watching.

I breathed in the forest smells from the hills above the village. Broad cedars, blue-green spruce, and the nodding tops of hemlock trees stood shoulder to shoulder on the hillside. The fog lifted and it was a clear-enough day to see a dozen miles down the coast to the offshore rocks where my father and uncle hunted seals. A sea stack to the north marked the entrance to Shipwreck Cove and the burn-scarred hillside behind it, where I was forbidden to go. In the hills behind me were the trails I took every spring to the berry fields and camas meadows.

I turned my face west to the level blue-gray ocean and listened to the voices of gulls and the slow rhythm of waves rocking against sand and stone. I settled on the cedar mat and set my eyes to watching, but Grandma’s words about quelans rang in my mind. Was I being disrespectful? I wished my cousin Henry was not out with the whalers. He always knew what to do about the things Grandma and Grandpa said, and I could count on him to be on my side. Still, they’d needed an eighth man. It was not so easy to get enough kinsmen together to run a whaling canoe, not since the war.

I thought over my conduct in the three days since Papa left. I had made my words honest and my body strong. I had settled my arguments. I had not complained . . . but I had been lonely. The room in the corner of Grandpa’s longhouse that Papa and I shared was dreary with him gone. The empty space hung over my dreams. Older dreams, dreams I fought off years ago, came back in that empty room in the dark. Dreams of my mother.

Five years had passed since her death. Five years since the soldiers came home from the war in Europe with their tan uniforms, cooking-pot helmets, burn scars, and influenza. My mother and our baby were sick for two days. They sweat rivers of salt with the fever, and then fell to gasping like a drowning person on dry land. They could not speak or even cry. We were a hundred strong in this village to welcome our soldiers home. A month later, there were sixty-one graves.

I could not let myself think of that. I made myself think of waves and whales’ voices and my father coming home. I drank rainwater from the cedar box. The sun was a few hours up from the horizon. I measured four hands between the setting sun and the calendar rock. Panjans, Grandma would call it, the last month of the year. March, they would call it at the schoolhouse up Neah Bay, Lent.

“I do not need to repent,” I said aloud. The whales were hard to find, but I could not believe that God would punish us. Hadn’t we given up our brutal traditions years ago? Slavery and raiding were not even a memory for me. We kept only the honorable customs. The Bible took its place with the most important stories. We had nothing to atone for. Still, the whalers had never been gone so long. I wondered if the sickness that followed our soldiers home from the war had settled in the ocean. Had the whales sickened and died? Had they disappeared as so many of our villages had? It took a year of prayer, sacrifice, and burning to clean the village after the influenza left. How could you clean the whole ocean?

The shadows grew longer, and I stood and swung my arms to keep off the chill. Far out and to the north, I saw a black stick on the horizon. My heart beat faster. I waited and hoped and prayed.

When I could clearly see the tall curved prow and tail of my father’s whaling canoe, I dashed for the trail down to the beach.

“The whalers are home!”

The joy of their return pulsed through my body. They were home, and I saw them first, and I would shout the news. It was so perfect that the stones on the path did not bruise my feet, and the nettles I brushed past did not raise welts. There was only the news and my voice shouting.

At the foot of the sea stack, I skidded to a halt. The tide had come up and covered the way to the beach, but I saw sand a foot under the water, so I drew a breath, and when the wave went out, I jumped. Salt splashed up and stung my eyes. I gathered my dress above my knees and ran for the shore. A wave crashed above my waist and drenched my clothes. I fought to find footing. The tug of the retreating wave made me stumble. I scrambled to my feet in the moment between one wave and the next and dashed up the beach. I took the porch steps in a single bound.

“Grandpa! They’re home!” I called, rushing to his workbench. He looked up from the mask he was painting. For a moment, a smile spread across his moon-round face, but then he put on his stoic leader-of-ceremonies look. He set his work aside and went to the massive chests at the back of the house to get out his regalia.

Aunt Loula didn’t even try to be dignified. She scooped me and my cousin Ida into a hug and let tears fall. She and Ida hustled off to their treasure chests to make themselves fine. Ida was already begging after this robe and that cedar crown.

I ducked into my room and kicked off my wet clothes. I took my best town dress off the peg and brushed out my hair. There was no regalia for me in my father’s carved and painted cedar chest. Years ago I had outgrown the button blanket my mother had made for me. I wore it far too long, dancing with it when it barely covered my knees. Last year, when it wouldn’t reach below the tips of my fingers, I knew I had to set it aside. Papa had promised me a new button blanket after we sold the whale oil. He traced out the pattern on heavy brown paper and promised a hundred dozen pearl buttons. Even though I didn’t have regalia of my own, I walked to the beach with my head high. I was the daughter of whalers.

The whole village assembled in rows, families of whalers first and all the others behind. Tall cedar hats showed who among us had hosted a giveaway. Red-and-black button blankets announced our lineage. The whale must know he gave himself for prosperous people. A rendering kettle was set to boil, and the drums and rattles were ready to sing. The long canoe pulled past the watching rock at the north end of the village and turned for the beach.

No whale.

The drums faltered and fell silent. The welcome song waited in my mouth. Seven silhouettes bent over their paddles. There was no shout or raised arms, no trail of seabirds and sharks. Grandma counted, “Pau, saali, chakla, muus . . .” She wept before she came to seven. I did not count. I knew where the harpooner sat. My body held still as stone, but my mind flew out over the ocean like a seagull looking north and south, crying in a gull’s one-note voice.

Gone. Gone. Gone.

2

The Forbidden Feast

A condolence call was what the Indian agent called it when he came two days later with his fast boat and fat mustache. He ran his boat up on the sand without a proper greeting or invitation. He looked around the beach for a few minutes, licking his thin lips, hoping to find something he could confiscate and then sell to the curio shop in town. He said he was here to pay his respects. He even remembered to remove his hat. I was suspicious already.

“I am sorry for the loss of Mr. Carver, a good man.”

The Mustache went on for many sentences, dishonoring us with the free use of a dead man’s name. Grandpa and Uncle Jeremiah met him on the beach, and I stood behind Grandpa’s shoulder, ready to translate words from English to Makah or read legal papers out loud. They spoke to the agent as honorably as they would any visiting chief, but Charlie went up to the watching rock to see if he had brought policemen, and Henry took men into the house to load rifles.

The agent went on in a fair-weather voice. Did we need the missionary? Should he send for a Black Robe? Could he take the orphan to school for us?

“It’s a fine Indian school with a long tradition, Chemawa in Oregon,” he said. “The girl would learn a trade. She would make a comfortable life, a domestic in some fine house in Portland or Seattle. It’s a bright future for this poor, fatherless girl, and a burden off your shoulders.”