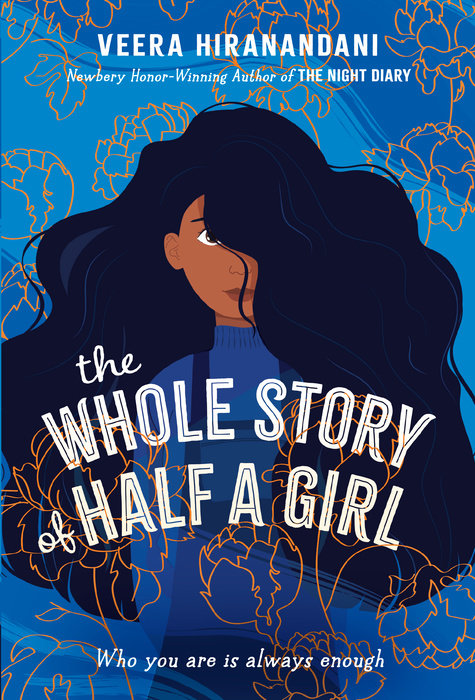

The Whole Story of Half a Girl

By the author of the Newbery Honor Book The Night Diary, a thoughtful and relatable story about cultural identity, friendship, and what it means to fit in without losing who you are.

After her father loses his job, Sonia Nadhamuni, half Indian and half Jewish American, finds herself yanked out of private school and thrown into the unfamiliar world of public education. For the first time, Sonia's mixed heritage makes her classmates ask questions—questions Sonia doesn't always know how to answer—as she navigates between a group of popular girls who want her to try out for the cheerleading squad and other students who aren't part of the "in" crowd.

At the same time that Sonia is trying to make new friends, she's dealing with what it means to have an out-of-work parent—it's hard for her family to adjust to their changed circumstances. And then, one day, Sonia's father goes missing. Now Sonia wonders if she ever really knew him. As she begins to look for answers, she must decide what really matters and who her true friends are—and whether her two halves, no matter how different, can make her a whole.

What greater praise than to be compared to Judy Blume!--"Each [Blume and Hiranandani] excels in charting the fluctuating discomfort zones of adolescent identity with affectionate humor."--Kirkus Reviews, Starred

An Excerpt fromThe Whole Story of Half a Girl

Chapter One

I’m in school, sitting with my hair hanging long down the back of my chair, my arm around my best friend, Sam. We’re planning our next sleepover. Sam’s parents have the tent and sleeping bags; her mom even bought us cool spy pen-flashlights just for the occasion. To top it off, it’s Friday and summer’s only two weeks away.

Jack, my teacher, passes out recipes from the next and last country our fifth-grade class will be studying--India. I look down and see the makings of biryani, which is a special kind of rice dish. Jack always teaches us about the country’s food first, then gives us the lay of the land and the history. Getting to know the food, Jack says, is the best way to really understand a country, just like sharing a meal with someone helps you get to know them. You can tell a lot from what a person eats. I agree. Jack always brings huge, delicious, sloppy sandwiches for his lunch, like meatball subs and Philly cheesesteaks, and that’s sort of how he is--a big, friendly, messy man.

Jack takes everyone into the school kitchen and we’re all assigned jobs. I have to measure the rice. Sam has to measure the spices. Other kids shell peas. Jack does all the chopping with the sharp knives. Before you know it, the rice is cooking and people are helping Jack sauté the onions, garlic, and spices. He tells everybody to stand back and holds the pan up, tossing all the ingredients like some super-famous chef, except Jack isn’t a super-famous chef and half of it lands on the floor. The delicious smells swirl around my nose and make my stomach growl. I love biryani. Life’s pretty good.

Then I get home. Mom’s face is all droopy--the way it looks when she’s upset. But she doesn’t say much. She just stirs and stirs something in a pot on the stove. I look in and see a mess of purple mush. Eggplant skins and empty tofu packages sit on the counter. Tofu makes my eyes hurt. It makes my head hurt. It makes my throat hurt. My younger sister, Natasha, appears on the stairs with her drumsticks. She starts drumming on the railing and Mom tells her to practice in her room. I go off to get my homework over with. I have an essay to write on what it’s like to live in India, but I don’t need to do any research. I just have to ask my dad. He was born there.

Finally, at dinner, while I’m trying to figure out why the tofu is so purple, Mom says, “Kids--”

And Dad says, “Wait, I’ll--”

And Mom says, “You should--”

And Natasha says, “Ha!” because she’s five years younger than I am and doesn’t know what to do with herself half the time.

And Dad says, “I have some bad news,” which explains why Mom’s acting strange and probably why the tofu’s so purple. His face looks red and a little puffy, like he’s going to cry. I’ve actually never seen my father cry. Two years ago my uncle died, Dad’s brother, and Dad didn’t cry at the funeral. Not that he wasn’t sad, because he looked sadder than I’ve ever seen him.

“I lost my job. I was fired,” he says. His eyes are wide.

Dad is, or was, head of sales for a company that publishes math and science textbooks. Sometimes he brings the books home. They’re really heavy, with very thin pages, and are meant for college kids. They have crazy titles like Fundamentals of Human Biology and An Introduction to Differential Geometry. It makes me dizzy just looking at the covers, which are always filled with graphs, numbers, and outlines or silhouettes of someone’s big smart head. Dad can understand them, though. He used to be a math professor at the same college where Mom teaches English literature. That’s where they fell in love.

The reason he was fired, Dad explains, is because he had a bad quarter.

“What’s a quarter?” I ask. He looks at me and tries to smile, but the corners of his mouth don’t quite make it. He takes a deep breath and rubs his chin.

“It’s a period of three months, a quarter of a year. Sales were down last quarter. Way down.”

“Oh,” I say.

A lot more questions zip through my head. Like why were the last three months so bad? Did he make someone really mad? Will he get another job? My heart speeds up, but I keep quiet. Natasha presses her fork into her purple tofu casserole, mashes it flat with the prongs.

“Who wants dessert?” Mom asks, even though we’ve all barely touched our dinner. She usually makes sure we’ve eaten enough of every weird thing she puts on the table, but I guess Mom doesn’t really want to eat her tofu casserole any more than we do. I get up and help her clean off the table. She takes mint chocolate chip frozen yogurt out of the freezer and starts to heap it in big white bowls lined up on the counter. I take a bite of mine, and for a moment, the cool minty sweetness is all I can think about.