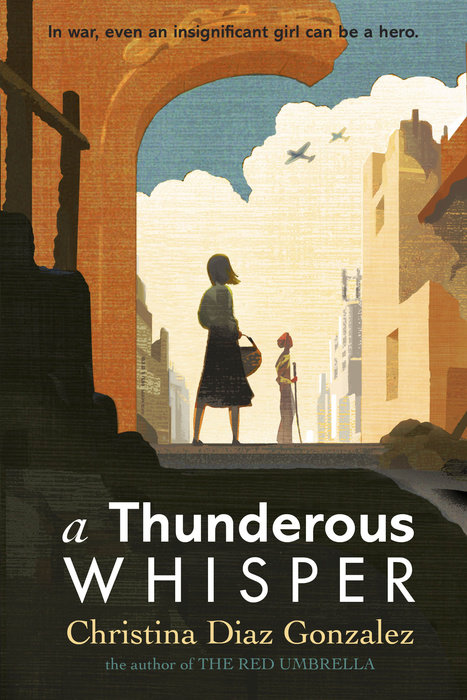

A Thunderous Whisper

"In the midst of the Spanish Civil War, 12-year-old ani unexpectedly gets drawn into a network of underground rebels working to thwart Franco's efforts to destroy the Basque people's way of life. . . . Exciting." -- SLJ

Ani believes she is just an insignificant whisper of a girl in a loud world. This is what her mother tells her anyway. Her father made her feel important, but he's been off fighting in Spain's Civil War, and his voice in her head is fading. Then she meets Mathias. His family has just moved to Guernica and he's as far from a whisper as a boy can be. Ani thinks Mathias is more like lightning. Mathias's father is part of a spy network and soon Ani finds herself helping him deliver messages to other members of the underground. For the first time, she's making a difference in the world.

And then her world explodes. The sleepy little market town of Guernica is destroyed by Nazi bombers. In one afternoon Ani loses her city, her home, her mother. But in helping the other survivors, Ani gains a sense of her own strength. And she and Mathias make plans to fight back in their own unique way.

An Excerpt fromA Thunderous Whisper

9780375869297|excerpt

Gonzalez / A THUNDEROUS WHISPER

One

Invisible. Irrelevant. Just an insignificant twelve-year-old girl living in a war-torn country. At least that’s what I’d been told.

And, really, no one ever seemed to notice me when they walked past the school’s large courtyard. They only saw the other girls laughing and giggling in small clusters under the building’s arches while the boys rushed out to challenge each other in a game of soccer or pelota vasca.

Rarely did anyone see the quiet, friendless souls . . . but we were there. Not really worthy of being picked on, we just came and went to school in silence. We rarely spoke to anyone, not even each other, although I could never remember why.

“Hey, you! Wait!” a voice called out from across the courtyard, near the steps that led to the cobblestone street below.

I had just walked through the school’s main door when I saw Sabino, a boy from my class, waving. Immediately I turned to look back inside, certain that he must be calling someone else.

“No, you . . . Sardine Girl,” he said. “Don’t let the door close. I forgot our ball inside.”

That’s what I was called—Sardine Girl.

My father would say our family’s clothes carried the scent of the sea, but that was just his fancy way of saying that we reeked of fish. It made sense since Papá had worked as a merchant seaman before joining the army and Mamá had always been a sardinera, selling the sardines that were the size of my feet, but stinkier, door to door. No wonder everything they owned, including me, smelled of fish.

I propped the door open with my right foot and stared as Sabino trotted toward me. He slowed down, and looking back at his friends, he pinched his nose.

They all laughed.

It wasn’t that I was surprised at being ridiculed. . . . Usually, I just ignored it. But, on that particular day, the sun in a cloudless blue sky seemed to be signaling the arrival of spring, and I, like the weather, was ready for a change.

And so, taking a deep breath, I waited until Sabino was about four feet away, and then I moved my foot. Kadunk! The door reverberated, and I heard the latch click shut.

“¡Idiota!” he shouted as he pushed past me, pulling on the locked door.

“My name is not Sardine Girl,” I muttered, my eyes never looking up from the ground.

lll

I followed the narrow cobblestone streets back toward my neighborhood, passing the shoe store, the fruit stand, and the people sitting at the small tables of the sidewalk cafés. Glancing up, I could see a few women in the balconied apartments pulling in the day’s laundry that had been hung out to dry.

I picked up my pace when I noticed that the large clock above the Plaza de los Fueros showed that it was already five-fifteen.

As I passed a few soldiers filtering into the local tavern, I couldn’t help wishing Papá were also on leave from the front lines. He could be so close—the front lines being less than twenty kilometers away—and yet the distance seemed so great. He felt farther away than when he’d leave for months on a merchant ship. Of course, this time he might not return home.

Rounding the final corner, where the last city street ended and the dirt road into the countryside began, I heard the sound of squeaky wheels approaching. As I stepped to one side, I saw two brown oxen pulling a large, mostly empty, rickety cart. As one of the beasts passed by me, it briefly turned its head, its eyes meeting mine, then, after a loud snort, it looked away.

“You don’t smell that great either,” I mumbled.

The farmer, walking on the other side of the street, next to the larger ox, gave me a friendly nod before cracking the whip against the animal. I could see there was a bit of a bounce to the old man’s step, which probably meant he had sold all his produce for a good price. At least someone was having a good day.

Actually, there were probably several people who were quite happy, as market days always brought an extra vigor to Guernica. Everyone in the region knew that Mondays in Guernica meant social events and jai alai games at the fronton after the market closed.

I loved Mondays too, but not because I wanted to socialize with anyone. No, for me this was the day that I didn’t have to sell sardines with Mamá or do chores. It was the one evening when I was free to do whatever I liked. So I was headed to the place where my dreams and stories were born.

It was really just a large open field with a big oak tree, but it had always felt like my special place. The tree was ordinary, similar in size to the famous Guernica Tree in the heart of the city, I suppose, but this one had no long history behind it. It was only special and significant to Papá and me.

From the time I was a little girl, whenever Papá was in town, he’d bring me to that tree. We’d have picnics, and I’d listen to tales of his travels. During the last few years, Papá had insisted that I come up with my own stories, and he’d lie back under the tree and get lost in my world of princesses and magical creatures. He always listened to every word I said, as if I were reading from the Bible, and when I finished, he’d usually smile and say, “Preciosa, tell me another.” And precious was how I felt.

I sighed. The last seven months of his being a soldier instead of a sailor had been like living on the edge of a crumbling cliff: any moment I feared that the land I stood on would give way. I couldn’t wait for the stupid war to be over and for life to go back to how it used to be. Without my father, the only good part of my day was going to class, and that wasn’t saying much. The only thing I liked about school was the books.

Walking up the mountainside, I clutched my sweater tighter to my chest as a cool breeze blew down the trail. Even in late March, on a beautiful afternoon, winter had not completely released its hold on northern Spain.

I had left the concrete and the muted colors of the city behind and stepped onto a grassy patch of land. Here I could drink in the brilliance of the sky, the green and brown of the neighboring mountains, and dream and forget the world around me.

I thrust my hand into my skirt pocket, and my fingers rubbed the edge of the satin pouch buried inside. It had been Papá’s gift to me before he left. A blue satin pouch made from the lining of his only suit. I grasped it and felt the small treasure it held. It was a reminder of all our days together.