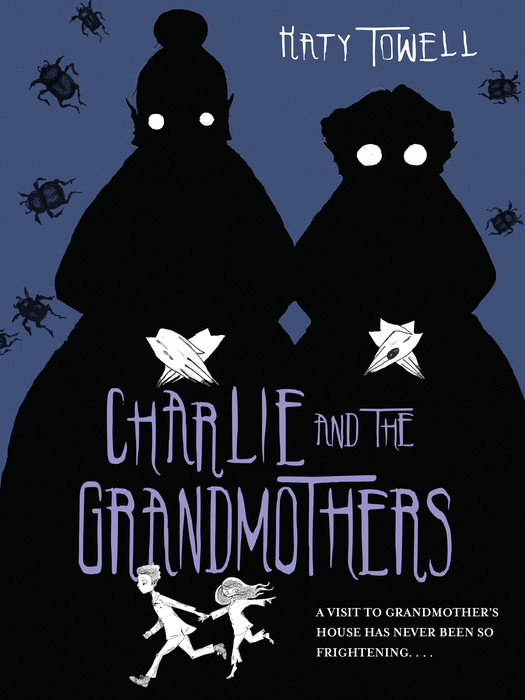

Charlie and the Grandmothers

Author Katy Towell

Charlie and the Grandmothers

A visit to Grandmother’s house has never been so frightening. . . .

Charlie and Georgie Oughtt have been sent to visit their Grandmother Pearl, and this troubles Charlie for three reasons. The first is that he’s an exceptionally nervous twelve-year-old boy, and he worries about everything. The second is that the other children in his neighborhood who pay visits to their grandmothers never seem to return. And the third is that Charlie and Georgie…

A visit to Grandmother’s house has never been so frightening. . . .

Charlie and Georgie Oughtt have been sent to visit their Grandmother Pearl, and this troubles Charlie for three reasons. The first is that he’s an exceptionally nervous twelve-year-old boy, and he worries about everything. The second is that the other children in his neighborhood who pay visits to their grandmothers never seem to return. And the third is that Charlie and Georgie don’t have any grandmothers.

Upon their arrival, all of Charlie’s concerns are confirmed, as “Grandmother Pearl” quickly reveals herself to be something much more gruesome than even Charlie’s most outlandish fears could have predicted. He and Georgie are thrust into a creepy underworld created from stolen nightmares, where monsters disguised as grandmothers serve an ancient, evil queen by holding children captive as they slowly sap each one of their memories and dreams.

But something is different about Charlie. His worrisome nature, so often a burden, proves an asset in this frightening world. Will he be able to harness this newfound power to defeat the queen and save his sister?

An Excerpt fromCharlie and the Grandmothers

Chapter One

Charlie and Georgie

Charlie was awake.

Charlie was always awake if he could possibly help it. He hadn’t slept properly in over six years. Not since that snowy February night when his slumber was broken by a pounding on the front door of the house, and a tall, sad man with his hat in his hands told Mother that an accident at the mill had taken Father away forever. Now when Charlie slept, he had bad dreams, and he would wake from these dreams with a terrible start, frightened that some new awfulness might’ve happened while his eyes were closed.

But it wasn’t a nightmare that troubled Charlie this night. What troubled him now was as real as the dark circles under his eyes. He’d been warning of it for some time, but of course nobody ever listened.

It was the children. All the children in town were disappearing, and Charlie knew that his sister and he were next.

In fairness to everyone who never heeded his warnings, it’s important to know that Charlie Oughtt was an exceptionally nervous…

Chapter One

Charlie and Georgie

Charlie was awake.

Charlie was always awake if he could possibly help it. He hadn’t slept properly in over six years. Not since that snowy February night when his slumber was broken by a pounding on the front door of the house, and a tall, sad man with his hat in his hands told Mother that an accident at the mill had taken Father away forever. Now when Charlie slept, he had bad dreams, and he would wake from these dreams with a terrible start, frightened that some new awfulness might’ve happened while his eyes were closed.

But it wasn’t a nightmare that troubled Charlie this night. What troubled him now was as real as the dark circles under his eyes. He’d been warning of it for some time, but of course nobody ever listened.

It was the children. All the children in town were disappearing, and Charlie knew that his sister and he were next.

In fairness to everyone who never heeded his warnings, it’s important to know that Charlie Oughtt was an exceptionally nervous twelve-year-old boy. He worried about flooding on a cloudless day. He worried about wildfires when the rain wouldn’t stop. He worried about things that went bump in the night and worried equally about things that didn’t. Charlie worried about everything all the time, and any attempt to reason with him only made him suspect your motives.

Charlie’s nervousness grew with him until it wrote itself upon his paper-pale face as plainly as the text in the books he was always reading. He wore two inverted parentheses between his eyebrows at all times, and there were commas at the corners of his perpetually downturned mouth. One curl of his short brown hair stood up on the back of his head like a question mark, and he bore a hyphen-shaped scar where he habitually bit into his bottom lip.

“Squirrelly Charlie,” his schoolmates called him, and sometimes “Oughtt the Distraught.” “Young Charlie is a well-mannered student who excels in every subject,” a teacher once wrote, “particularly in gym class, where he performs expertly as a hurdle.”

Mother often said to herself that she wished Charlie were just a little bit more like his sister, to which she would invariably add, “and if only his sister were a little bit more like him.” For Georgie Oughtt had never been afraid of anything in all her eight years. Rarely was there a day when she did not come home with a muddied frock or a scraped-up shin or with the landlady angrily pulling her along by the ear.

“Well, Georgie Louise, what have you to say for yourself this time?” was how Mother’s lectures always began.

“I’m awfully sorry, Mama,” Georgie would sweetly say, “but when adventure comes calling, how can an adventurer say no?” (Adventurers, she would then be reminded, sometimes needed to sit silently in their bedrooms for the rest of the day.)

Mother was very patient with her troubled worrier and her intrepid adventurer, for that is just the sort of person Mother was. Patient, kind, understanding. But Mother was also very sad. Sometimes she sighed for no reason that anyone could see, and often she fell very quiet. She almost always smiled, but it was a melancholy smile, and all the pretty jigs she taught her piano students sounded like elegies by the end of each lesson. Because Mother was so very lonely, it pained her to be away from her children for even a moment.

“I don’t know how Mr. and Mrs. Thomas can bear to have their girls so far away!” she sighed when little Ellie and Margaret from Georgie’s class went off to visit their grandmother one July.

“I’m sure it will be a wonderful time for the boy, but my heart aches for his mother,” she said when one of her students left for a trip to see his grandmother the following August.

“It doesn’t make you unhappy to see your friends travel when you’re stuck here with me, does it?” she asked Georgie when the children from three doors down went to visit their grandmother in September.

“Not as unhappy as it would make me to leave you,” Georgie answered, though this had only been half true.

“I don’t want to travel anywhere, Mother,” Charlie said, which was true as true could be. “We might be overtaken by train robbers, and who would take care of you then?”

Their answers made Mother smile in her sad way, especially when the twins from upstairs left in October.

“They’re going away to visit their grandmother, aren’t they?” Charlie asked as he watched them board a coach in the pouring rain. Mother didn’t answer right away. Instead, she stopped playing her woeful tune and peered at Charlie from over the piano.

“You’ve got that tone in your voice,” she said.

“They are, aren’t they?” Charlie returned. “They always do.”

“The twins?”

“All the children. They’ve all been going away, and they always have the same reason. It’s . . . it’s . . . it’s odd is what it is.”

“What’s so odd about it?” Georgie asked as she prepared a poultice for her latest run-in with poison oak. “Lots of children go to visit their grandparents. I’m sure we would do the same if we had any left, and if you weren’t afraid the sky would fall on us.”

Mother resumed her playing and tsked at Georgie’s manners at the same time. There was the usual be-nice-to-your-brother-Georgie-Louise and the typical but-she’s-right-you-know-Charlie, and so Charlie kept his concerns to himself for a time. Meanwhile, the other children continued going away, one after another, even in the first blizzard of January.

“It just isn’t normal,” Charlie insisted one day, his nose pressed to the parlor window, his breath making the glass fog. “Their parents aren’t even waving goodbye.”

“It is a bit unusual,” Georgie agreed, tracing a skull and crossbones in the foggy spot with her finger, “but if it’s not a trip to see their grandmother, what else do you suppose it is? I’ve seen a lot in my time, you know. I’ve been to every corner of our block. Often enough, Charlie-O, things are exactly what they appear to be. No matter how much I’d like for them to be a treasure map, sometimes they’re just an advertisement that’s bled through a wet newspaper.”

“I really wish you wouldn’t go digging up soggy garbage, Georgie. Think of all the mold spores you’re breathing in,” Charlie warned. Once, he’d read an article about a man who’d been the picture of health until his house flooded and subsequently mildewed. When the man took ill and died, the doctors opened up his head to find his brain as moldy as old cheese. It was weeks before Charlie would go near anything damp without holding his breath.

But Charlie wasn’t really thinking about mold now. He was thinking that of all the children who had gone away since July, not one of them had come back. And no one but he seemed to mind. At least Georgie and I are safe, he thought. Mother would never send us away. She needs us here.

Then February came, and a colder, darker February Charlie could not recall. He already loathed the month as it was. His worst dreams plagued him relentlessly on the snowy nights of February. And now the sun had begun to disappear as early as noon while the snow fell so heavily that one had to bat the stuff out of the way in order to see where one was going. As usual, nobody found this as alarming as Charlie did.

“The days are always shorter in winter,” reasoned Mother.

“All this gorgeous snow and not one friend around to throw a ball of it at,” Georgie harrumphed.

Charlie shook his head impatiently after the umpteenth round of this and swore to himself he’d give up while wondering why he bothered at all. But he knew very well why he bothered. He bothered because he believed in every one of his bones that some evil lurked in those snowy black nights, and if he closed his eyes too long, it would come in and snatch away all that he loved. In truth, he had always felt so, but everyone told him not to let his imagination run away with him. Now that the night came so unnaturally early, and what with all the kids he knew drifting away, Charlie couldn’t be satisfied that all his years of fearful expectation were the product of nervous fancy.

So, night after night he waited, hunched over his favorite encyclopedia volume with a mug of hot black coffee to keep him awake. Morning after morning, Mother would find him shivering under his blankets and would have to promise him that whatever threat he had perceived was now long gone with the morning sun.

But then came the darkest night of them all.

It was a distinct and almost tangible darkness that made the hair stand up on Charlie’s neck. It jolted him from his reading and compelled him to peek through his curtains, where he saw, to his great alarm, nothing. No streetlamps, no wandering beam from the distant lighthouse. The moon had turned black, and while he watched, the very stars went out. Soon after, the noise he usually took for granted long into the night was silenced all at once. No carts rolling on cobblestones, no chatter from late-shift dockworkers, no seagulls screeching. It was as if some great awful being were cupping its hands over the world to snuff it out. Then Charlie’s own lamp sputtered and died, leaving him in blackness with a thundering heart.

What if it’s me? he thought. What if I’ve gotten myself so frightened that all my senses are short-circuiting? Maybe everything is completely fine out there, and I’ve just gone deaf and blind. Oh dear. That isn’t any better at all!

Charlie’s senses were not on the fritz, it turned out, a fact soon proved when he heard a voice coming from his mother’s room next door. Charlie slipped out of bed and, after stumbling about in the darkness, found the wall and pressed his ear to it.

“Yes,” he heard Mother murmur. “That . . . would be . . . lovely. Pearl. I . . . always . . . loved . . . that farm . . . of pearls. . . .”

Farm of pearls? She must be dreaming, Charlie thought. But then he heard a sound that made his breath catch in his throat. It was another voice. A strange, whispering voice only just audible to the sort of person who makes a practice of listening for strange voices.

“See the world, the worldy-worldy-world,” it hissed in a childish way.

“They should . . . experience . . . the world. Shouldn’t . . . keep them here . . . all the . . . time. . . .” Mother yawned.

“Sleep now. Sleepy-sleepy-sleep!”

“I . . . have been . . . so very tired. . . .”

“Happy! So happy! No need for kiddies!”

Charlie ran to the curtain that divided his half of the room from his sister’s, slipping on the rug in the process. He scrambled to his feet again, ignoring the pain in his undoubtedly bruised knee, and hissed, “Georgie! Georgie, wake up! Someone’s in Mother’s room!”

He fumbled for the curtain and pulled it back. In the darkness so absolute, he couldn’t see his sister, but there was no mistaking her snoring. Georgie could have slept through a hurricane, and trying to wake her up always proved a waste of time. But there wasn’t any time to waste, and Charlie knew he couldn’t bury himself in his blankets now.

“Mother!” he shouted, and after much clattering and stumbling and knocking over of things, he made his way to their mother’s room and threw open her door.

When he looked inside, however, he saw no one in the room but Mother. The terrible darkness had lifted. All was illuminated by the hazy glow of the moon now. Through the sheer curtains on Mother’s window, the streetlamps kept their usual watch. Below, the fishmongers sang while they packed up their wares, just as they did every night. It seemed then as if all Charlie had witnessed before had happened days ago, his memory of it disintegrating like the horror of nightmares by morning.

“Charlie?” Mother mumbled groggily, half sitting. “What’s going on? Are you all right? What’s happened?”

“Nothing,” Charlie said, feeling like a fool. “It was just a bad dream.”

Nevertheless, when Charlie returned to his own room, he peeked out his window once more, just to be sure. He saw a policeman idly pacing the boardwalk. A seagull was decimating a crab. A stray cat perched atop a barrel and cleaned its paws. All under the flames of streetlamps that dotted the night’s fog like ghost lights. Everything was as it should be.

And yet something caught Charlie’s eye. Standing but a few yards from the apartment house was a very old woman in a dusty, tattered dress, her shaggy hair draping her hunched shoulders. She leaned on a wooden cart full of junk and was accompanied on either side by a pair of what Charlie supposed were small children, though their clothes and hats were so oversized that he couldn’t see their faces. They could’ve been trained monkeys for all he knew.

Charlie was still puzzling over this when he noticed that the old woman was staring right at him. There could be no mistake about it. Their eyes met, and she grinned, showing teeth as gray as her hair. Charlie gasped and pulled his curtains closed.

It’s just some old rag-and-bone woman, he told himself. Isn’t there anything in the world I’m not afraid of?

Charlie lay awake the rest of the seemingly ordinary night, staring at the utterly average ceiling until the unremarkable sun rose in the morning and shone plainly through the perfectly normal window. His weariness made his head feel like a strongman’s barbell, but that wasn’t anything out of the usual for him. Nor, for that matter, was the embarrassment from having panicked over nothing yet again.

Perhaps everybody’s right about me, he thought. At least the boy who cried wolf knew when he was making it all up.

He reached out and took his alarm clock from his night table and examined its off-white face. The time was six-fifty-nine, and in exactly thirty-four seconds, the copper bells on top would start clanging away. Charlie never needed the alarm to wake up. He just liked that it was something he could count on every single day, without any surprises at all, as long as he remembered to wind it. Whenever Charlie felt as rotten as he did now, he looked to his alarm clock, and then everything seemed all right again.

But not everything was all right, for drifting from the kitchen was the sound of Mother humming. Not just humming, he noted with concern, but humming happily. Charlie sat up slowly, all his bones popping and cracking the way one’s grandfather’s might. Then he depressed the button that would quiet his beloved alarm clock before it rang unnecessarily and went to investigate this mystery of Mother’s good cheer.