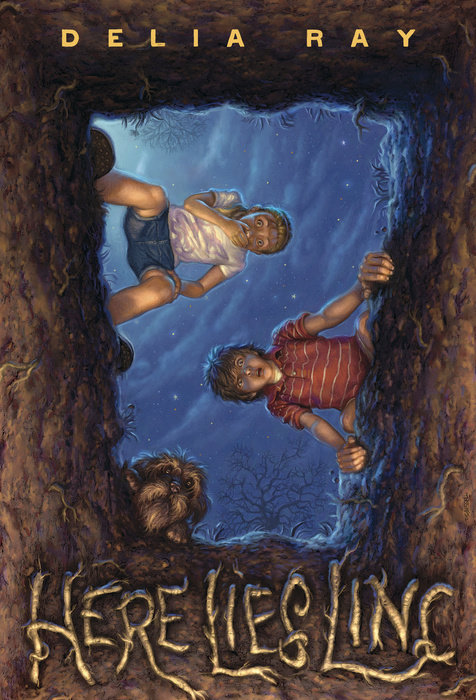

Here Lies Linc

When 12-year-old Linc Crenshaw decides he wants to go to public school, his professor mom isn't so happy with the idea. He's convinced it will be the ticket to a new social life. Instead, it's a disaster when his mom shows up at their field trip to the local cemetery to lecture them on gravestones, and Linc sees her through his fellow-students' eyes. He's convinced his chances at a social life are over until a cemetery-related project makes him sought-after by fellow students he's not so sure he wants as friends, helps him make a new, genuine friend, and brings to light some information about his family that upends his world.

Delia Ray has written a funny, heartfelt story about a lonely kid and his mother as they ultimately cope with the grief left behind from his dad's death, and along the journey find new ways to connect with each other, and their community.

An Excerpt fromHere Lies Linc

Plainview Junior High was supposed to be a fresh start for me. But it’s hard to start fresh when kids keep asking you questions about your past. During the first week of school at least ten kids had tried to strike up conversations.

They always started the same way.

“You’re new, right? Where’re you from?”

“I’m from around here.”

“Then how come I’ve never seen you before? Which elementary school did you go to?”

“Uh . . . you’ve probably never heard of it,” I’d say. “It’s really small.”

“Oh, you mean Washington Elementary? Or Kennedy?”

“No. . . .”

“Well, which one?”

“Uh—”

“Which one?”

“Well, it’s called the Home-Away-from-Homeschool. A retired professor runs it out of her basement. It’s sort of like a homeschool . . . but, you know, away from home. There were only a few of us. . . .”

That’s about the time their ten pairs of eyes would cloud over and their ten pairs of feet would find an excuse to shuffle away.

And that’s about the time I started to think that maybe I had made a big mistake switching to public school. Part of me wished I was back in Dr. Lindstrom’s stuffy basement with the other oddball university professors’ kids who made up the Ho-Hos. That’s what Dr. Lindstrom had called us—the Ho-Hos, short for Home-Away-From-Homeschoolers.

Next to the typical Ho-Ho—like Sebastian, who could list every ancient Egyptian ruler back to King Khufu and wrote his name in hieroglyphics on the top of all his papers, or Vladka, who came from Russia and hardly ever spoke above a whisper and could multiply five-digit numbers in her head—I felt downright ordinary. I had transferred to Plainview hoping to find more regular kids like me. Lottie had always said if I really wanted, I could switch schools once junior high rolled around. But after just a few days at Plainview, I began to realize that I must be a full-fledged Ho-Ho after all, with extra cream filling on the side.

Still, I kept trying to fit in, and I was doing a pretty good job of it until the end of September, when Mr. Oliver made his surprise announcement in American Studies class.

That afternoon’s lecture on the settlement of the Midwest territories hadn’t exactly been riveting. So to entertain myself, I had grabbed a Kleenex from the box on the windowsill beside my desk and, like a surgeon, gotten busy dissecting the tissue into two see-through layers. Once the dissection was complete, I tuned back in, just in time to hear Mr. Oliver say, “And listen up, people! I’ve got some good news. Next week you’ll actually have a chance to see where some of our city’s most famous settlers are buried, because we’re all going on a field trip to Oakland Cemetery.”

While the rest of the kids whooped and high-fived over the prospect of missing class for a day, I froze in my seat, trying to make sense of the weird coincidence.

But Mr. Oliver wasn’t finished.

“And, people . . . ,” he said, pausing for effect while We the People waited, “here’s the best part. I’ve managed to convince one of the nation’s premier cemetery experts to come over from the university and lead our tour. Her name is Professor Charlotte Landers.”

Lottie.

Why didn’t she tell me?

If the sport of blushing could be an Olympic event, I’d win the gold medal. I’ve always turned beet red without a second’s notice, even over dumb stuff like having to answer “Here” during attendance or if a halfway-decent girl happens to look in my direction or if Lottie sends me to the grocery store for something embarrassing like diarrhea medicine or dandruff shampoo.

So obviously, as soon as Mr. Oliver called out my mother’s name, I felt my cheeks start to turn the color of raw hamburger. I grabbed a dissected tissue from my desk and pretended to blow my nose, bracing myself for the next part of the announcement, the part when Mr. Oliver would tell everyone that the graveyard expert’s son was, in fact, a member of our very own fifth-period class. I waited with my face buried in the wad of Kleenex, praying for the blood to hurry up and drain back to where it belonged, into my overactive arteries and capillaries and veins.

A few more long seconds passed, and when I didn’t hear my name called, I lifted my face out of the tissues, inch by inch, and looked around the room. But Mr. Oliver had already turned back to the blackboard, and the kids in the next row were busy copying down details of a new assignment. I slumped back in my desk with relief. . . . Nobody knew. For some reason Lottie must not have told Mr. Oliver that she was my mother. And since we had different last names, no one had any idea that we were even related.

Still, by the time school ended that day, the upcoming field trip had lodged itself like a splinter in my brain. The timing couldn’t have been worse. Right when the Ho-Ho questions were starting to die down, now this—Lottie leading my class on a tour of the graveyard. It’s not that I didn’t love my mother. I loved her more than anything. It’s just that she was kind of . . . kind of unusual. The way she thought and talked and dressed, everything about her was different from other moms. I knew the kids in my class weren’t prepared for the likes of Lottie Landers.

She called home that night to check on me—from some tiny town on the coast of Rhode Island where she was spending a week of research in an old slave cemetery. This would be the longest Lottie had ever been gone, and she had insisted on hiring one of her graduate students to “take care of” me while she was away, even though I had become pretty good at running things around the house over the past few years. Luckily I had barely seen the guy since he’d shown up on our doorstep with his four bags of laundry the day before.

I wanted to interrogate Lottie about the field trip the minute I picked up the phone, but I forced myself to hold back until she had finished telling me about how her research was going. I couldn’t remember the last time she had sounded so excited.