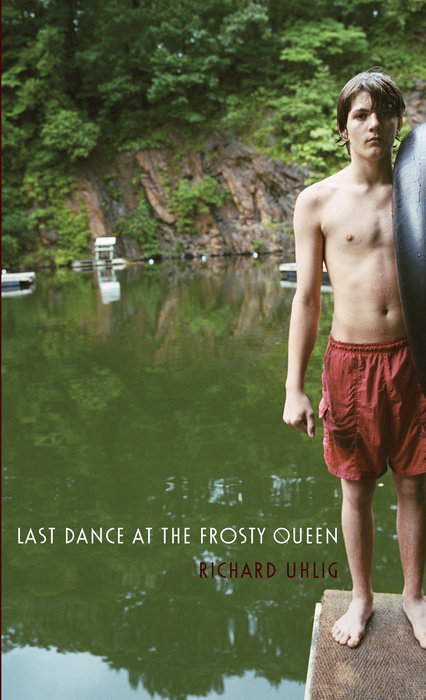

Last Dance at the Frosty Queen

On the dock of a lake in a tiny town at the corner of Nowhere & Nowhere, he sits counting the seconds until his high school graduation—at which point Arthur M. Flood intends to leave his hick life far behind in the brown Kansas dust. That's the plan. Until . . . up from the lake's muddy depths swims a girl. She's not a mermaid, but she is the one who shakes up Arty's life, makes him mad and mad for her, and helps him find a pathway to his past, his future, and where his heart truly lies.Teens will recognize their own emotional landscape in this steamy, funny, coming-of-age tale in which the heart tries to hide, only to be utterly exposed by love and lust, lost and found.

An Excerpt fromLast Dance at the Frosty Queen

I wheel the Death Mobile onto Broadway, my hometown’s main drag, and head west. Pierre, my bosses’ standard poodle, sticks his delighted-doggie head out the window, his tongue flapping. The digital thermometer on the savings and loan blinks 93 degrees—and it’s only May 6. They say it’s going to be a scorcher this summer, and the air-conditioning in my hearse is fatally busted.

A big white banner flutters overhead: harker city, kansas—celebrate our one hundred years this memorial day weekend! Celebrate what? Here it is 1988, and if you’re in the mood for McDonald’s, Chinese food, a movie, or even a stoplight, you’ll have to drive thirty miles north and swing a right at Junction City.

Our Broadway might not have much in the way of shows, the cheesy promotional brochure in City Hall tells you, but we make up for it in our traditional small-town friendliness.

Harker City’s slogan is “1,700 smiling faces—and yours!” Of all the things this burg lacks, dateable girls would have to be at the top of my list. My class, the seniors, has twelve girls in it, right? Three have children, two are pregnant (say what you will, but we yokels know how to entertain ourselves), one is my cousin, one is becoming a nun, one is morbidly obese, and the decent-looking remainders date football players. If you don’t play football in Harker City, you don’t exist (I don’t exist).

I drive past our house, the plain-looking two-story white clapboard with a big front porch. Carrie, my sister, wants to paint the exterior Victorian rose with sky blue trim, but Dad’ll never go for it. Way too flashy. The sign on the lawn says flood & son funeral home, serving harker city since 1922. Dad added this a few years ago, when those awful Larsons moved to town and built a sprawling new Southern Colonial–style funeral home across the street. The Larsons, beaming yuppies with giant white teeth, live in a big house with a swimming pool out by the country club. The “son” in Dad’s sign is my big brother, Allen, whose official title is assistant funeral director, a position that allows him to lie on his bed all day and smoke pot.

My dad, the bald guy who looks like he might be expecting twins, is in our driveway washing his new used hearse. He’s growing that grizzled beard for the Centennial.

Five minutes later, hot wind whips my hair as we zoom past the rusted marquee of the old Chief Drive-in Theater. Town soon gives way to wheat fields as my speedometer hits seventy. The stand-up twenty-four-karat-gold wreath-and-crest hood ornament reminds me that I am driving a genuine Caddy. A gift from Dad on my sixteenth birthday, this black 1965 hearse, with its rusted frame and chrome-draped grinning face with dual headlights, accelerates like a cement truck going up Pikes Peak and gets about eleven miles per gallon with a stiff breeze behind it.

Gleaming in the sun, lined with cabins and trees, Harker City Lake stretches out before us.

I pull off the lake road into the rutted drive next to where we used to live. The mailbox leans way over, the m. flood stenciled on top just barely visible. I see that swallows have nested inside, and that cheers me up a little. The driveway is overgrown with weeds, and I worry that after last night’s rainstorm I’ll get stuck. But the earth feels solid under my tires as I park beside the foundation of our old house. You can still see the char on some of the stones. The fireplace is all that stands and a tree grows out where the kitchen once was. I think about Mom cooking in there and I try to remember her face, but the picture is too hazy. I’m amazed at how small the house must’ve been—seemed so much bigger then. It’s been nine long years since it burned down.

I grab a Snickers from the glove compartment. It’s soft from the heat and when I tear it open, the chocolate runs. It’s been raining like crazy all spring and the water is nearly up to the road. I amble down to the small floating dock with Pierre and sit and nibble the Snickers while he marks the cattails. It’s windier out here than in town, and the bouncing platform makes me horny. I lie back and stare at the cotton-ball clouds and listen to the water slap the wood. I imagine I’m on a giant water bed with Olivia Newton-John rocking and riding me. My eyelids grow heavy.