Chapter One

MORNING LIGHT

A big fruit boat passes, rocking our gondola hard. Paolina tumbles against me with a laugh. I put my arm around her waist and hug her.

Paolina squirms free. "It's too hot, Donata." She pulls on one of my ringlets and laughs again.

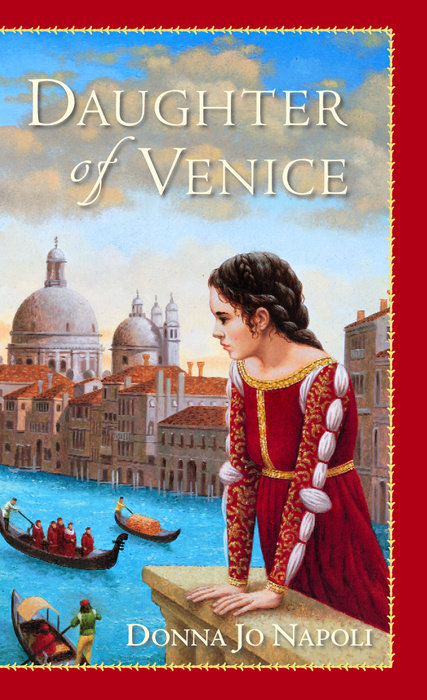

Yes, it's hot, but it's a wonderful morning. The Canal Grande is busy. That's nothing new to us. From our bedchamber balcony my sisters and I watch the daily activity. Our palazzo stands on the Canal Grande and our rooms are three flights up, so we have a perfect view. But down here in the gondola, with the noise from the boats, and the smell of the sea, and the glare of the sun on the water, not even the thin gauze of my veil can mute the bold lines of this delightful chaos.

Our Venice, called La Serenissima, "The Most Serene," is frenzied today.

My feet start to tap in excitement, but, of course, they can't, because of my shoes. Whenever I go on an outing, I wear these shoes. They have wooden…

Chapter One

MORNING LIGHT

A big fruit boat passes, rocking our gondola hard. Paolina tumbles against me with a laugh. I put my arm around her waist and hug her.

Paolina squirms free. "It's too hot, Donata." She pulls on one of my ringlets and laughs again.

Yes, it's hot, but it's a wonderful morning. The Canal Grande is busy. That's nothing new to us. From our bedchamber balcony my sisters and I watch the daily activity. Our palazzo stands on the Canal Grande and our rooms are three flights up, so we have a perfect view. But down here in the gondola, with the noise from the boats, and the smell of the sea, and the glare of the sun on the water, not even the thin gauze of my veil can mute the bold lines of this delightful chaos.

Our Venice, called La Serenissima, "The Most Serene," is frenzied today.

My feet start to tap in excitement, but, of course, they can't, because of my shoes. Whenever I go on an outing, I wear these shoes. They have wooden bottoms thicker than the width of my palm; I have to practice before venturing out, or I'll fall. And even then, I go at Uncle Umberto's pace--a blind man's pace. I look in envy at Paolina's zoccoli, her sandals with thin wooden bottoms. Paolina is only nine and she hasn't been subjected to high shoes and tight corsets yet.

"Can I take my shoes off, Mother? Just for the boat ride, I mean."

"Of course not, Donata."

"But I hate these shoes. They keep me from doing what I want."

"That's exactly why you should wear them." Mother reaches across Paolina's lap and gives a little yank to my wide skirt so that it lies flat over my lap. "High shoes make sure young ladies behave properly."

"Because we're afraid of falling? But you always say proper behavior comes from proper thoughts."

"Keep your shoes on, Donata. And don't make remarks like that when we arrive." Mother sits tall herself. "We're almost there now. Be perfect ladies, all of you."

Laura, my twin, sits facing me, with our big sister Andriana beside her. Laura stretches out her right foot so that her shoe tip clunks against mine. She's grinning under the white veil that hides her face, I'm sure of that. The very idea of my being a perfect lady is absurd. I grin back, though, of course, Laura cannot see my face, either.

Andriana's hands are in her lap, the fingers of one squeezed in the other so hard that her knuckles stand out like white beads. Mother's words make her throw her shoulders back and stretch her neck long. Underneath Andriana's veil, she is far from laughter; I bet her lips are pressed together hard.

Mother grew up the daughter of a wealthy artisan--a citizen, not a noble. There are three kinds of Venetians: plain people, who cannot vote and whose needs and rights must be protected by the nobles; citizens, who can vote but not hold office; and nobles. Mother was lucky to marry into Father's noble family. We all know that, but Andriana is the one who worries about it. She worries that our questionable breeding casts doubt on her worthiness as a bride. But she needn't. Andriana is sixteen, two years older than Laura and I. She's ready for a husband. And she'll get one easily. The oldest daughter in any noble family marries, even if she's ugly. And Andriana, with her wide-set, hazel eyes and delicate, pointed chin, is stunning. The mothers at the garden party today will all want her as a daughter-in-law.

If Andriana is lucky, she'll marry someone young and handsome. How I wish that for her. There are too many old widowers around looking for brides. The breath of decrepit Messer Corner, his exaggerated limp, the gray hair from his ears pollute my thoughts. That can't happen to Andriana. Father would never choose poorly for her, no matter how rich a suitor was. Andriana will marry someone vigorous, most certainly. She will have children.

Children. The youngest in our family is Giovanni--already three years old. There are twelve of us: Francesco, who is twenty-two; Piero, twenty; Antonio, seventeen; Andriana, sixteen; Vincenzo, fifteen; Laura and I, fourteen; Paolina, nine; Bortolo, six; Nicola, five; Maria, four; and Giovanni, three.

Giovanni is Mother's last child. That's what Mother says, at least. Father likes to say, "Things happen," and he winks. But I'm old enough to understand that Mother is probably right about this. Giovanni is our only brother who still sleeps on the same floor of the house as the girls, and I adore him. We all do. He'll probably move down to the small boys' floor soon. I miss having a baby in the house.

My heart squeezes. I want to take Laura's hand, but she's sitting too far from me. Laura and I have to be careful today--as careful as we can. The perfect ladies Mother wants us to be. For we, too, hope to marry someday. Both of us.

We've never voiced that hope to anyone else--it's a whisper between us in the dark. We know very well that if we hadn't been born twins, one of us would be the third sister and unmarriageable, for a nobleman is lucky to marry off one daughter and blessed to marry off two--he cannot hope to marry off more than two. But twins should be a special case--it's impossible to think of one of us marrying but not the other.

I place my feet primly together and sit up tall like Mother and Andriana.

The gondola veers into a side canal and the water is instantly calm and quiet. And smelly. This small canal is shallower than most, so the filth people throw into it can stink for days before it's finally washed out to the open waters of the lagoon. Hot weather brings the most foul odors.

The gondoliere in the front leaps onto the step and offers his hand to us, while the gondoliere in the back steadies the boat against the docking pole. I stand and hold on to one of the supports of the tent we've been riding under in the center of the gondola. Sweat rolls down my thigh. It's hot for late spring. I'd like to lift my skirts high and let a breeze tickle my bottom. But that's exactly the sort of behavior I must avoid today. I raise my skirts only high enough to allow me to step out of the boat.