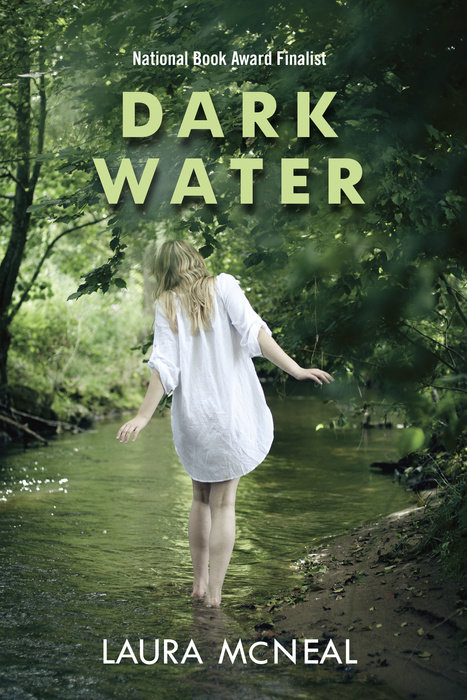

Dark Water

A National Book Award Finalist

A Kirkus Reviews Best Books for Teens

Fifteen-year-old Pearl DeWitt lives in Fallbrook, California, where it's sunny 340 days of the year, and where her uncle owns a grove of 900 avocado trees. Uncle Hoyt hires migrant workers regularly, but Pearl doesn't pay much attention to them...until Amiel. From the moment she sees him, Pearl is drawn to this boy who keeps to himself, fears being caught by la migra, and is mysteriously unable to talk.

Then the wildfires strike.

An Excerpt fromDark Water

One

You wouldn't have noticed me before the fire unless you saw that my eyes, like a pair of socks chosen in the dark, don't match. One is blue and the other's brown, a genetic trait called heterochromia that I share with white cats, Catahoula hog dogs, and water buffaloes. My uncle Hoyt used to tell me, when I was little, that it meant I could see fairies and peaceful ghosts.

Then I met Amiel, and for six months it seemed true what he whispered in his damaged voice: Tú eres de dos mundos.

He was wrong, of course. You can only belong to one world at a time.

Now that he's gone, I try to see things when I'm alone. I put one hand over my blue eye, and I look south. With my brown eye I can see all the way to Mexico. I fly over freeways and tile roofs and malls and swimming pools. I cross the Sierra de Juárez Mountains and the Sea of Cortés to the place where Amiel was born, and I find the turquoise house with a red door. There are three chairs on the covered patio: one for him, one for me, and one for Uncle Hoyt. I tell myself the chairs are empty because we're not there yet. I watch for as long as I can and when my eye starts to water, I remove my hand.

Tomorrow, I'll look again.

Two

People move to Fallbrook, California, because it's sunny 340 days of the year. They move here to grow petunias and marigolds and palms and cycads and cactus and self-propagating succulents and blood oranges and Meyer lemons and sweet limes and, above all, avocados. They move here to grow them, I should say, or to pick them for other people.

The houses are far apart when you're out in the hills, where trees and petunias grow in straight lines for profit, but once you get close to town, the streets look like something drawn by a child with an Etch A Sketch. No overall plan, no sidewalks, just driveways going off in crazy lines that lead to other driveways, where signs point to other dead-end streets named in Spanish or English with no particular theme--La Oreja Place sticking out of Rodeo Queen Drive leading to Tecolote Avenue, which if it were a sentence would read "the Ear on the Rodeo Queen of the Owl."

The ear and the queen and the owl are overrun with bougainvillea, ivy geraniums, tulip vines, and star jasmine, and that's what makes Fallbrook beautiful from a distance but tangled and confusing up close. It's a place where you can get lost no matter how long you've lived here, and there are only two roads out, something we didn't think much about before the fires began.

Three

I first saw Amiel de la Cruz Guerrero on the corner of one of those Etch A Sketch streets, where Alvarado meets Stage Coach. I was fifteen and he was seventeen, although he told employers he was twenty. I was in my sophomore year of high school and my mother was substitute-teaching because my father had left us, and as my mother was constantly saying over the phone when she thought I wasn't listening, The wolf is at the door.

Every weekday morning at seven-thirty we'd leave my uncle's avocado ranch, where we were living free of rent (but not shame) in the guesthouse. My mother would drink her coffee in the car while she drove, and I would eat dry Corn Pops from a Tupperware bowl. Traffic would bunch up as all the cars going to all the schools had to inch through the same four-way stop at Alvarado and Stage Coach, one corner of which was a day-labor gathering site, meaning Mexican and Guatemalan men would stand around on the empty lot hoping to get a day's work digging trenches, moving furniture, hauling firewood, or picking fruit. The men stared intensely into every car, hoping to win you over before you stopped. Pick me, their faces said. The wolf is at the door.

But on this morning, the men had their backs to the road. Our car rolled slowly to the stop sign, going even slower than usual because the drivers of the cars were staring, too.

When we got close enough, I could see a lanky guy in a flannel shirt and work pants doing some sort of act. Fallbrook calls itself the Avocado Capital of the World, so you don't live here without seeing guys pick avocados. Mostly it's done on high ladders, but there's also this funky tool like a lacrosse stick with a six-foot handle. You stick the pole way up in the tree, hook the avocado, yank, then lower the pole so you can drop the fruit into a huge canvas bag you're wearing slung over one shoulder and across your chest. That's what Amiel was doing that morning, only without the pole, the sack, the tree, or the avocado.

"What in the world?" my mom asked.

"He's picking imaginary fruit," I said.

She snuck a look. "That's the oddest thing I've ever seen."

"Can we hire him?"

She snorted. It was our turn to dart through the intersection just as Amiel de la Cruz Guerrero touched his imaginary avocado-picking pole to a live electrical wire and received an imaginary jolt, which made all the day-labor guys laugh.