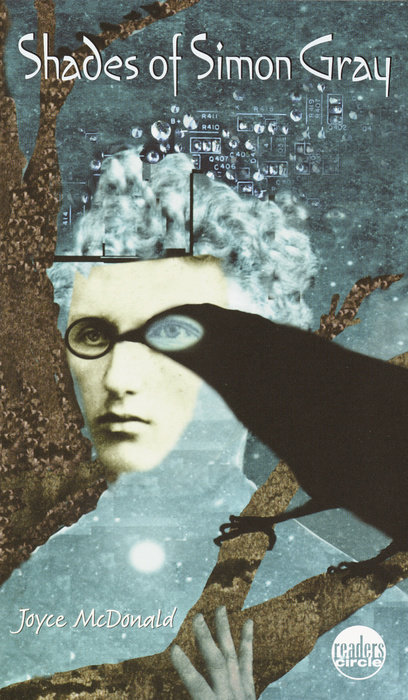

Shades of Simon Gray

Author Joyce McDonald

Shades of Simon Gray

Simon Gray is the ideal teenager — smart, reliable, hardworking, trustworthy. Or is he? After Simon crashes his car into The Liberty Tree, another portrait starts to emerge. Soon an investigation has begun into computer hacking at Simon’s high school, for it seems tests are being printed out before they are given. Could Simon be involved?

Simon, meanwhile, is in a coma — but is this another appearance that may be deceiving? For inside his own head, Simon can walk around and talk to some people. He even seems to be having a curious conversation with a man who was hung for murder 200 years ago, in the branches of the same tree Simon crashed into. What can a 200-year-old murder have to do with Simon’s accident? And how do we know who is really innocent and who is really guilty?

An Excerpt fromShades of Simon Gray

Chapter 1

On the night Simon Gray ran his '92 Honda Civic into the Liberty Tree, the peepers exploded right out of the local streams, shrieking like souls of the dead disturbed from their slumber, louder and more shrill than anyone in Bellehaven could remember. Like the plague of frogs converging on ancient Egypt, they were everywhere: in window boxes, on front porch rockers, in mailboxes carelessly left open, in gutters. They even clogged a few exhaust pipes.

Most people in town were absolutely positive the peepers caused Simon's accident. With squashed frogs all over the road, their blood, like so much oil, made driving slippery. It was bound to happen to somebody. A few suspected that the sudden appearance of the peepers might be a curse. But this was an unpopular view, Bellehaven being a respectable and upright town.

When the police found no skid marks, nothing to indicate that Simon Gray had slammed on the brakes for dear life, that was no surprise. Everyone knew he would have. He was the responsible young man who baby-sat…

Chapter 1

On the night Simon Gray ran his '92 Honda Civic into the Liberty Tree, the peepers exploded right out of the local streams, shrieking like souls of the dead disturbed from their slumber, louder and more shrill than anyone in Bellehaven could remember. Like the plague of frogs converging on ancient Egypt, they were everywhere: in window boxes, on front porch rockers, in mailboxes carelessly left open, in gutters. They even clogged a few exhaust pipes.

Most people in town were absolutely positive the peepers caused Simon's accident. With squashed frogs all over the road, their blood, like so much oil, made driving slippery. It was bound to happen to somebody. A few suspected that the sudden appearance of the peepers might be a curse. But this was an unpopular view, Bellehaven being a respectable and upright town.

When the police found no skid marks, nothing to indicate that Simon Gray had slammed on the brakes for dear life, that was no surprise. Everyone knew he would have. He was the responsible young man who baby-sat their children, walked their dogs, and watered their plants while they were on vacation. The boy who had cleaned their gutters, mowed their lawns, and run their errands since he was ten.

They were sure the slick mess on the road would have made finding any trace of tire treads impossible. Not one single person in town doubted that for a minute, and if anyone hinted otherwise, people turned away and wandered off without finishing the conversation.

Come sunrise, following the accident, what remained of the peeper population had settled back into the streams and the muddy banks of the Delaware, but for the next two weeks they continued their piercing chirps after the sun went down. By the time they finally stopped, everyone in town knew the truth about Simon Gray.

Or so they believed.

On the day before the accident, a heat wave settled over Bellehaven like a cloud of steam. It all but sucked the air out of anyone who tried to take a deep breath. Some attributed special significance to its being April Fools' Day. But most simply found it odd to have eighty-five-degree temperatures in early April, shrugged, and went on about their business, although they were inclined to move at a much slower pace. Only the Delaware River, swollen with the spring runoff and freshly stocked with brook and rainbow trout, sped along at breakneck speed, spewing white foam over rocky ridges.

When the heat wave persisted through the following day, girls dug out last year's shorts and tank tops from attic trunks in preparation for school on Monday, and threw away lipsticks that had melted in their backpacks. By nightfall, people found themselves kicking off top sheets, digging window fans out of basements and attics, and wrapping ice cubes in face towels to lay across the backs of their necks. A few even turned on air conditioners, muttering about future electric bills that were sure to leave them paupers.

But the heat wasn't all that kept Simon Gray awake as he paced his airless bedroom that night, wearing only a pair of boxer shorts. He hadn't slept in two nights, and it didn't look as if he ever would again. Unlike everyone else in town, he barely noticed the temperature creeping toward ninety. He had other things on his mind.

When he slipped on a pair of khaki cargo shorts and a black T-shirt, silently sneaked out the back door, got in his car, and headed for the river, it wasn't in search of cooler air. What he sought was a few moments of peace. A rare minute or two when something or someone besides Devin McCafferty and the others didn't monopolize his thoughts.

He parked his Honda near the boat ramp and headed down to his favorite spot a few feet from the Delaware. For the next half hour he watched the moonlight glimmer off the rush of water heading downriver, letting his mind flow along with it. People, he realized, were a lot like drops of water caught up in the spring runoff, shuttled into fast-moving streams that collided into rivers and rushed to join the ocean. If you got caught in the current there was no turning back. The only way out of that racing water was to evaporate into the night air.

Evaporate. Disappear.

He wondered what it would feel like to be as light as mist, to no longer be weighted down with a human body filled with leaden fears, in constant dread of being discovered, exposed, humiliated.

Simon turned his face toward the sky so thick with stars he could almost taste them on his tongue, metallic, like biting into aluminum foil. Moonlight glinted off his thick glasses, and anyone looking at his face would have thought his eyes had melted into two pools of pure light.

Sitting with his back against the base of a huge white pine, eyes closed, he listened to the gentle hush-hush, the whisper of the wind through the soft needles. For just the tiniest moment Simon thought he might float up into the night air and beyond. Until the piercing shrieks of two raccoons, probably males hell-bent on killing each other over a female, forced him to remember why he was here, why he hadn't been able to sleep.

He did not want to think about what would happen to him, to all of them, if they were caught. But then, maybe it was time he was caught, because he'd been fooling everyone for so long he'd started to fool himself. Simon the Eagle Scout. Simon the Responsible. Squeaky clean Simon. Hell, he was Bellehaven's very own Dudley Do-Right. Who was he kidding?

Even when he was caught stealing a computer game the previous fall from CompUSA, the manager, who turned out to be his old second-grade teacher, Mr. Grabowski--the upgraded Mr. Grabowski, ex-teacher, now a hotshot manager--had merely given him a friendly pat on the back and said, "Guess you had your head in the clouds, there, Simon." He had pointed to the box Simon had tucked inside his jacket. "I think you forgot to pay for that."

Yeah, right. Was the guy that dense?

Simon had lifted the box from its hiding place and said, "Oh, yeah. Sorry." And that was all there was to it. Later he realized that Mr. Grabowski hadn't wanted to believe Simon would stoop to stealing from his store. Simon himself still had no idea why he'd done it. It was the only thing he'd ever tried to steal in his life, and now he couldn't even remember the name of the computer game.

What was it with people anyway? Why did they trust him? Especially with their kids? Lately he'd taken to letting the kids do exactly what they wanted, eat Oreos and fistfuls of Froot Loops and Cocoa Puffs until they spun like twirling tops from all that sugar. He let them watch cartoons until their eyes popped right out of their heads. He liked to see the kids happy. It made him feel good.

When that didn't work, he would sometimes set them in their cribs or their playpens and let them cry until their throats were hoarse and their noses so clogged they could barely breathe. Their sobs brought him much too close to the edge, much too close to his own tears, tears he'd worked hard to control. That was when he would walk right out the back door, sit under the nearest tree, and wait for the silence, because he couldn't bear to listen to their cries. Because he didn't know how to take away their pain.

Simon folded his arms and tucked his hands beneath them. He stared out over the river. If those same moms had followed him around this past year, they would have been horrified. They would have locked their children in their rooms for safekeeping, kept their pets in their basement, shuttered their windows, pulled down their shades, and shunned the very sight of him. He imagined that even his own mother, if she had still been alive, would have turned away from him.

Sometimes, on nights when the sky had just begun to turn violet, and strange shadows seemed to hover along the edge of his backyard where it ran into the neighbor's field and to the cemetery beyond, Simon thought he saw his mother rising from her restful place beneath the pines, where she had been buried more than a year earlier, to shake her head in disapproval. On such nights, he would see her at the edge of the field, and if he stared long and hard enough, squinting into the thin line of muted orange on the horizon, if he blurred his vision ever so slightly, he could almost make out the disappointment on her face.

On these nights, he was convinced she knew everything he had ever done and considered him beyond redemption. On other nights, when he was willing to cut himself a little slack, he told himself such notions were childish fantasy. Still, despite this rationale, he had discovered he preferred the shadowy form of disapproval, hovering beyond the edge of his yard, to nothing at all.

It was almost midnight and Simon's eyelids felt heavy. The lack of sleep was catching up with him, and now it seemed his mind was beginning to play tricks, because suddenly tiny frogs were springing out of the weeds, leaping off rocks, and sending their shrill calls into the night. They flew into Simon's lap, landed in his hair, crawled into the pockets of his cargo shorts.

Frantic, he jumped to his feet, beating the frogs from his head, all the while trying not to step on any of them as he made a dash for his Honda. Dozens of frogs crawled over his car. Fortunately he had left the windows up. Still, the peepers clung to the windshield like tiny suction-cup toys. Simon pounded his fist at them from the inside, but they refused to budge. If he turned on the windshield wipers he could launch the peepers right into outer space. Then again, maybe not. Maybe he would end up with a windshield smeared with frog guts, making it even harder to see. Forget the windshield wipers.

The rearview mirror was useless. The entire rear window was coated with frogs. So were the side windows. The only way he could see to back out was to roll down his window and risk letting the frogs inside the car. He rolled the window down a few inches, enough to peer out, then pulled out of the parking lot, hoping that once he was away from the river the frogs would disappear. But to his amazement, they were everywhere. They rose out of neatly manicured lawns and bounced along the tops of boxwood hedges; they were all over the road. And the sound, as he drove over them--hundreds, maybe thousands--was the sound of tar bubbles popping on a sun-scorched road.

He had never seen anything like this before--not in all the years he'd lived in Bellehaven--not in his entire life.

As Simon approached the community park with its fifteen-mile-an-hour speed limit, the car continued to speed along--fast, then faster. With any luck at all, the frogs would blow right off the windshield. But they hung on. The faster Simon went, the louder the popping noises from beneath his tires. Desperate, he turned the radio up full blast to drown out the horrible sound.

As he passed the park--a perfect square surrounded on three sides by stately Victorian homes and the county courthouse on the fourth--he had the bizarre sensation of being in a dream. Maybe all this was a hallucination brought on by lack of sleep. He'd heard of such things. Or maybe the hallucination was the result of the heat.

As he squinted through a clear space of glass in between the frogs, Simon's eyes fell on the huge white oak up ahead. It was the oldest tree in the county, dating back to the Revolutionary War. A battle-scarred soldier. The road had been lovingly built to curve around its thick roots. Beneath its sprawling branches a tarnished bronze plaque proclaimed this the Liberty Tree.

But Simon and the other kids at school called it the Hanging Tree because more than two hundred years before, a drifter named Jessup Wildemere was hanged from its branches for murdering Cornelius Dobbler right in his own bed while he slept, stabbing him so many times the blood formed a pool on the floor, seeped through the crevices, and stained the ceiling of the parlor below.

Up ahead, a dark shadow seemed to rise out of the damp earth in front of the bronze plaque. The shadow shifted, grew filmier in the glare of Simon's headlights, but he could see it had a form--the shape of a man.

Simon's breath caught in his throat. He was so startled by the shifting figure in front of him, he didn't realize he was still flying along at fifty miles an hour. And when he did notice, it was too late. In his panic his foot slammed down on the gas pedal instead of the brake. The car's engine roared in response. The Honda hydroplaned over the slick surface, going so fast Simon thought the car had sprouted wings. His fear was replaced with a sense of wonder, a sense of absolute freedom. He felt himself being lifted right into the air. Like a drop of water evaporating, he was out of the river. Yes!

The sirens didn't wake Danny Giannetti because he hadn't yet gone to bed. He sat on the porch roof outside his bedroom window, watching in wonder as, below, thousands of peepers converged on the front lawn. If he lay on his stomach and leaned carefully over the edge, his fingers clamped on the rusting gutter guards, he could see the frogs on the steps, on the porch railing, on the pillars. Their green bodies, almost black in the moonlight, were dark splotches on the white paint.

His first thought, when the emergency siren sounded, was that the town had declared war on the frogs. He half expected to see fire trucks tear down the street, firefighters blasting holes in the blanket of frogs with their hoses, half expected a cavalcade of police cars, with sharpshooter cops hanging from the windows, firing nonstop as peepers sprang into the air, looking like clay pigeons as they leaped for their lives. But the emergency siren stopped. And the distant moan of police car and ambulance sirens didn't seem to be coming anywhere near Maple Avenue, where Danny lay on the porch roof, listening carefully.

Once in a while, if you paid close attention, Bellehaven might give up one of its secrets. Somewhere in town behind one of these closed doors, maybe a life-and-death emergency was unfolding. Or maybe a crime, a robbery, or even a murder. Danny was hopeful, beside himself with anticipation.