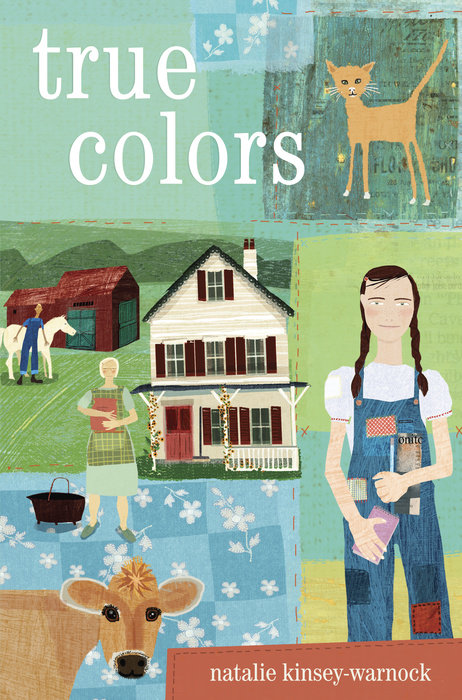

True Colors

Author Natalie Kinsey

True Colors

Natalie Kinsey-Warnock's beautifully told, warm hearted novel tells the story of one girl's journey to find the mother she never had, set against the period backdrop of a small farming town in 1950s Vermont. For her entire life, 10-year-old Blue has never known her mother. On a cold, wintry day in December of 1941, she was found wrapped in a quilt, stuffed in a kettle near the home of Hannah…

Natalie Kinsey-Warnock's beautifully told, warm hearted novel tells the story of one girl's journey to find the mother she never had, set against the period backdrop of a small farming town in 1950s Vermont. For her entire life, 10-year-old Blue has never known her mother. On a cold, wintry day in December of 1941, she was found wrapped in a quilt, stuffed in a kettle near the home of Hannah Spooner, an older townswoman known for her generosity and caring. Life with Hannah so far has been simple—mornings spent milking cows, afternoons spent gardening and plowing the fields on their farm. But Blue finds it hard not to daydream about her mother, and over the course of one summer, she resolves to finally find out who she is. That means searching through the back issues of the local newspaper, questioning the local townspeople, and searching for clues wherever she can find them. Her search leads her down a road of self-discovery that will change her life forever.

An Excerpt fromTrue Colors

Chapter 1

June 1952

On a cold, clear December day in 1941, when I was but two days old, on the very same Sunday the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, I was found stuffed into the copper kettle Hannah Spooner grew her marigolds in. Even though I was wrapped in a tattered quilt, my skin was blue, bluer than a robin's egg, as blue as the tears I imagined in my mother's eyes when she left me there, with not even a note pinned to my diaper to give a clue as to who I was or where I'd come from.

Hannah carried me inside and warmed my cold, still body in her oven, just as she had newborn lambs, until I was pink again and squalling for my supper.

As news spread through town, folks nearly tripped over each other rushing out to Hannah's farm to see the Kettle Baby.

"Why, Hannah!" her friends said. "You're sixty-three years old! You can't be raising up a child at your age." But Hannah had decided to keep me, and I love her…

Chapter 1

June 1952

On a cold, clear December day in 1941, when I was but two days old, on the very same Sunday the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, I was found stuffed into the copper kettle Hannah Spooner grew her marigolds in. Even though I was wrapped in a tattered quilt, my skin was blue, bluer than a robin's egg, as blue as the tears I imagined in my mother's eyes when she left me there, with not even a note pinned to my diaper to give a clue as to who I was or where I'd come from.

Hannah carried me inside and warmed my cold, still body in her oven, just as she had newborn lambs, until I was pink again and squalling for my supper.

As news spread through town, folks nearly tripped over each other rushing out to Hannah's farm to see the Kettle Baby.

"Why, Hannah!" her friends said. "You're sixty-three years old! You can't be raising up a child at your age." But Hannah had decided to keep me, and I love her like flowers love the sun, but still, bringing creatures home is Hannah's nature, so I figure I was just one more creature that needed nursing back to health. All these years, I've wondered what was wrong with me to cause my real mother to throw me away as if I were nothing more than a banana peel or a day-old newspaper.

So when I saw the cat near Hannah's barn, wild-eyed and skinny as a rake handle, and Hannah said it'd likely been left behind last year by one of the summer people when they headed back to the city, I felt my heart snag like cloth on a blackberry bramble.

"I know just how you feel," I told the cat.

I carried a bowl of milk out, but the cat took off across the pasture. I set the bowl down, anyway. She might come back.

Hannah didn't know it, but I had a secret. All these years, I've been waiting and watching for my mama to come back, too.

I looked down the road, as I did every day, but it was empty. She might not come today, or tomorrow, but someday she'll show up, saying how she made a terrible mistake, that she didn't know what she was doing when she left me, that she really loves me and wants me back. I'll kiss Hannah goodbye, climb into my mama's brand-new 1952 DeSoto, and off we'll go to see the world.

Every once in a while, Hannah saves out enough of her egg money to take me to the movies (she especially loves Humphrey Bogart), and we share a root beer float at Pierce's Pharmacy, but my real mama will take me to the movies every day, and she'll buy me ice cream for breakfast, dinner, and supper if I want.

"Blue?" Hannah's voice carried out to me and chased the dreams from my head. "Are you feeding that cat out of my good china?"

You heard right. Hannah named me Blue--Blue Sky, to be exact--for my eyes and for being the same color, when she found me, as that clear December sky. Hannah says she thought long and hard about what to name me. I think she should have thought longer and harder, and come up with something better. I know hound dogs and cows with better names than I got, but I guess I'll have to live with it, at least until my real mama comes to claim me, and then I'll have a whole new name to go along with my new life.

Chapter 2

Hannah's was the last farm near Shadow Lake. Even though it was a small farm--only seven cows, a couple of sheep, and some chickens--the summer people enjoyed coming by to help with the haying or to let their children ride Hannah's old white horse, Dolly.

"See this?" they'd tell the children as we forked hay onto the wagon or milked the cows by hand. "This is how things were done in the olden days."

Everything on the farm was old, but Hannah kept it all neat and tidy, and her flower garden was so beautiful no one noticed that the porch roof sagged or the barn needed paint.

The summer people may have thought it was fun to spend some of their vacation helping out, but for Hannah and me, summer was work. Besides doing the everyday chores of feeding the animals, milking the cows, cleaning gutters, spreading manure, and collecting eggs (which the hens always hid in at least a dozen different places), there was haying to be done. It could take all summer, and it was hot, itchy, backbreaking work. When it looked like there'd be at least three dry days in a row (and three dry days in a row in Vermont is about as common as a whistling pig, Hannah says), Hannah hitched up Dolly to the mower and mowed like crazy. After the sun dried the grass, we raked it so the sun could dry out the underside, too, then pitched the hay up onto a wagon, took it to the barn, and pitched all that hay off the wagon into the barn bays. We had to put up enough hay to feed the livestock through the whole winter (and winter in northern Vermont can last seven months).

Sometimes when summer people talked about how farming was so relaxing, I just wanted to shake 'em till their teeth rattled.

"Relaxing, my foot," Hannah would say.

One thing about all that work--I was strong. I could lift the full milk cans into Mr. Hazelton's truck when he came to pick them up every morning, and I could carry a hundred-pound bag of grain. Hannah was even stronger. She could lug two bags of grain, one under each arm.

"We're not women to be trifled with," Hannah says.

Then there was the gardening. Hannah had a huge garden that had to be tilled, planted, and weeded all summer long, because it fed us all winter, too.

When we weren't working, we went berrying. Picking berries was Hannah's idea of fun, but to me, it just seemed like more work. Hannah and I picked pails of wild strawberries (it takes hours to pick a pail of tiny wild strawberries, and as much time to hull them, but even I had to admit there was nothing better-tasting than wild strawberries), wild raspberries, currants, gooseberries, and blueberries.

Besides milk and eggs, Hannah sold home-baked goods to the summer people, and I delivered them on Dolly. Those summer people couldn't get enough of Hannah's pies (made with all those berries we picked), bread, cakes, muffins, and her famous doughnuts. We would have been hard-pressed without that money, but every week, Hannah managed to save out a few dollars to put into a jar she'd labeled BLUE'S COLLEGE FUND.

Hannah was proud of that college fund, but it made me nervous. I didn't even like grade school--what made Hannah think I was going to like college? I hadn't decided yet whether I was going to run away and join a circus (I didn't like clowns, but I could see myself as a lion tamer) or go out west and be a cowboy. Either way, Hannah was in for a big disappointment.

It wasn't just the summer people who ordered Hannah's baked goods. She had dozens of regular customers, spread out over ten miles, and no matter how late it was, or how tired I was, or how much in a hurry I was, Mrs. Wells had to tell me about how her bunions were acting up, or how her daughter's baby was teething, or show me pictures of her ancestors who'd been dead about a thousand years. Every time I had a delivery for her, I wished I could just toss her order onto the porch as I was riding by, like a newspaper.

"She's lonely, poor thing," Hannah would say when I complained. "It won't hurt you to spend a few minutes listening to her."

The Trombley farm wasn't a short stop, either. Mr. Trombley had gotten his arm caught in a dragsaw and had spent two months in the hospital. Neighbors had pitched in to do his chores and haying, and all the women had been taking turns bringing in meals. Hannah sent a big basket every week, packed with enough food to feed a small army, which I guess the Trombleys were, seeing as how there were seven kids. Those kids were always climbing all over me, wanting to see what I'd brought, wanting me to play with them, and wanting to ride Dolly. It was hard to get away.

After the Trombley farm, my next deliveries were in town. As I rode past the fairgrounds, I saw banners saying SESQUICENTENNIAL! I wouldn't have understood what that meant except I knew this summer was the town's 150th anniversary. Four days of activities were being planned: a parade, a speech by the governor, pageants covering the town's history, horse pulling, harness racing, a bake sale, a supper in the town hall, and fireworks. It was going to happen August 13 to 16, and would be the biggest celebration this town had ever seen.

My last stop was the Monitor office. The Monitor was our weekly newspaper, and every Wednesday, I delivered three dozen doughnuts there. Wednesday night was when everyone at the office stayed up late making up the paper, which meant getting it ready to be printed, and even here, outside, I could hear the thump and clack of the printing press, which would be running all night. There was always so much excitement at the Monitor on printing nights that I wished I could stay up all night with them, but I knew Hannah wouldn't let me do that (Who'd help me with the chores in the morning? I could hear her saying), so I had to be content with watching them for a little while after I delivered the doughnuts. The editor, Mr. Wallace Gilpin, said he didn't think they could get the paper out without Hannah's doughnuts to keep them going. Mr. Gilpin always gave me a nickel, and I'd rush over to the five-and-ten-cent store before it closed and buy penny candy. I'd agonize over what to pick--root beer barrels, Tootsie Rolls, licorice sticks, horehound drops, bubble gum--then buy one of each, and they'd last most of the ride home.

Dolly stopped right at the Monitor door; she knew our route so well I often thought Dolly could make the deliveries all by herself (but then I wouldn't have gotten my nickel). I slid off her back, carried the bag of doughnuts up the steps, and was just reaching for the doorknob when the door burst open and Raleigh True charged out, barreling right over me.

Chapter 3

The bag of doughnuts went flying. So did I, though Raleigh didn't even stop to see if I was all right, which wasn't like him. He disappeared around the side of the building, and then I heard shouting.

I should have run inside and gotten Mr. Gilpin, but Hannah's always saying I don't think before I act, and I guess she's right, because I ran after Raleigh instead.

Behind the Monitor office was where the river ran through town. At one time, it had been a busy place, with mills all up and down along the river, but most were now fallen in, with weeds growing in and around them. Teenagers liked to hang out in those old buildings, and they were littered with cigarette butts and broken beer bottles.

Waterfalls tumbled down the hillside, where, every spring, I liked to watch the steelheads leaping the falls, on their way upriver to spawn. Almost every day, I'd see Mr. Hazelton fishing in the river, but he wasn't there today. Too bad, because he might have been able to stop what happened.

First thing I saw was Raleigh cradling a heron in his arms. The second thing I saw was Dennis and Wesley swaggering toward him, just like the showdown between Gary Cooper and the bad guys in High Noon, except Gary Cooper wasn't holding a heron.

"Hand it over, Frankenstein," Dennis said.

From a nest high in a tree, three baby herons hopped and squawked for their mother. All I could think was that Dennis and Wesley must have been throwing rocks and knocked the heron from its nest, and Raleigh must have seen them through the window.

Dennis and Wesley Wright were known throughout town as the Wright brothers, but they were as far from Orville and Wilbur as boys could get, I imagined. They'd started smoking and swearing when they were four, and were stealing and setting fires by the time they started school. They burned down Mr. Emerson's outhouse, tried to burn Mr. Hazelton's garage (his dog ran them off), and threw a firecracker into Mrs. Gauthier's chicken coop. Those poor hens were so traumatized they never laid eggs again and ended up in the soup pot. Since then, the Wright brothers had moved on to smashing mailboxes and windows, slashing tires, and stealing anything that wasn't chained down. The only thing I had in common with them was that they didn't have a mother, either. I remembered Hannah telling me once how Mrs. Wright had died giving birth to them, leaving Mr. Wright to raise the boys. Hannah had sighed and shaken her head.

"They would have been better off being raised by wolves," she'd said.

I thought she might be right, except the wolves probably would have been terrified of them, too. Dennis and Wesley were even meaner to animals than they were to other kids. They'd tied a firecracker to Dolly's tail and lit it, which might explain why Dolly was terrified of fireworks, and once in the horse shed at school, Dolly got stung over a hundred times after the Wright brothers peppered a hornets' nest with green apples, which might explain why Dolly was terrified of hornets and the Wright brothers. But of all the people and animals they terrorized, Raleigh was their favorite target.

Raleigh wasn't a kid--he was thirty-one years old (I knew that from counting the candles Hannah had put on the cake she'd made him for his last birthday), but he was "slow." He only spoke a few words, and it was hard to tell how much he understood of what other people said. Raleigh had a lopsided grin and a dent in his head, just above his ear, where the hair didn't grow. He did look a little like Frankenstein, though I would never have called him that. Hannah said he'd had an accident ten years ago, but she didn't say what kind of accident, and the one time I asked her about it, she'd changed the subject, so I didn't ask again. I wish I had; it would have saved us a lot of heartache later on.