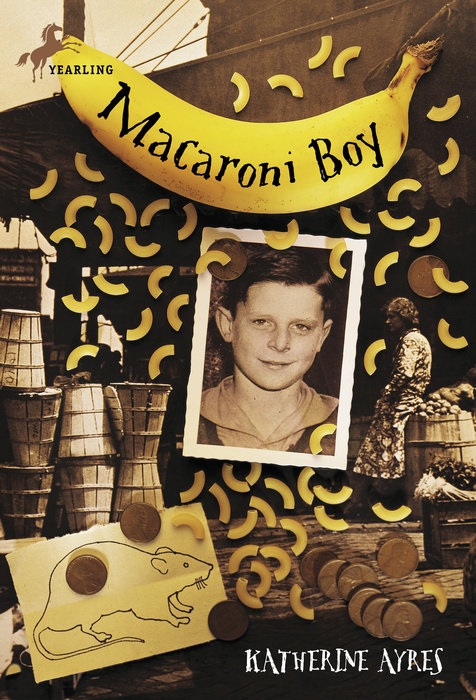

Macaroni Boy

During the Great Depression, a boy who faces bullying stumbles upon a mystery and comes of age in this novel that integrates fact and opinion and has a rich 1930’s vocabulary. Extra material: An Author’s Note is included in the back of the book.

Mike Costa has lived his whole life in The Strip, Pittsburgh’s warehouse and factory district. His father’s large Italian family runs a food wholesale business, and Mike is used to the sounds and smells of men working all night to unload the trains that feed the city. But it’s 1933, and the Depression is bringing tough times to everyone. Money problems only add to Mike’s worries about his beloved grandfather, who is getting forgetful and confused.

Mike is being tormented at school by a loud-mouth named Andy Simms, who calls Mike “Macaroni Boy.” But when dead rats start appearing in the streets, that name changes to “Rat Boy.” Around the same time Mike notices that his grandfather is also physically sick. Can whatever is killing the rats be hurting Mike’s grandfather? It’s a mystery Mike urgently needs to solve in this atmospheric, fast-paced story filled with vibrant period detail.

An Excerpt fromMacaroni Boy

1

Macaroni Boy

"Hey! You! Macaroni Boy!"

Mike Costa whirled. He'd recognize that voice anywhere--Andy Simms, the worst kid in the Strip. And I have the rotten luck to have him sitting right next to me in Sister Mary John's sixth-grade class.

As Mike searched the sidewalk and alley behind him, his fingers curled into fists. With weasel-faced Simms on the loose, a guy needed to be ready.

"Macaroni Boy!" The shout came again, louder and closer this time. "I got a present for you."

A small, round blur flew in Mike's direction. He jumped backward, but not in time. Something smacked hard against his legs, spattering as it landed. Cripes, a rotten apple. Before he could take a breath, two more apples hit, mashing brown goo onto his socks and shoes.

"I'll get you for this," Mike shouted, running in the direction the apples had come from.

"Got to catch me first!"

Mike's shoes slapped against the pavement and he rounded the corner by a fruit market. As he raced onto the side street, he caught a glimpse of Simms, half a block ahead, ducking into an alleyway. Shoving past empty vegetable crates, Mike pushed his legs harder and turned into the alley, closing the distance between them.

In the narrow brick confines of the alley, Simms was a moving shadow, but Mike was sturdy and fast. He reached out to grab at Simms' skinny shoulder. "Got you, you punk."

"Says you, Macaroni Boy." Simms twisted away.

Mike ran and reached again, this time catching a good grip on the sleeve of Simms' coat. "You're a louse, Simms," he growled. Pulling closer, he aimed his fist at the kid's jaw and let it fly.

Simms ducked and the blow connected solidly with the side of his head. He grunted, then spun around and shoved, driving Mike belly-first into the railing of a fire escape. Simms yanked hard, freeing his arm.

For a moment Mike couldn't move, couldn't even breathe, his chest hurt so bad. By the time he could stand up and look around, all he could see was a brick wall. He ran his fingers along his ribs--sore, but nothing felt broken. His lungs burned as he tried to catch his breath, but each time he breathed in, a rotting, apple-y smell hit him smack in the nose.

He kicked at an empty tin can and sent it spinning up the alley, wishing he could kick Simms like that and send the bum into the cold, filthy water of the Allegheny River.

Mom would get after him for this, Mike knew. She had enough to do, keeping up with all the ordinary washing and ironing, she didn't need extra. He dragged himself from the alley and checked his legs to see how bad the damage was. His knickers seemed clean enough, but reddish-brown apple slime covered his socks and shoes.

Mike sped along Penn Avenue, past small shops and big food warehouses. He didn't stop until he reached 29th Street and his house. Ducking into the backyard, he peeled off his socks and shoes first. Cripes, even my legs are covered, he thought. If Mom sees this I'll be in for it. Maybe I can clean up quick and nobody will know.

Careful as a cat burglar, he eased open the back door and peered into the kitchen. Nobody. He inched inside and headed for the cellar stairs. Once in the cellar, he grabbed a tin pail and set it under the hot water tap. While the pail filled, he collected old rags and the bar of strong soap Mom used for washing clothes.

Phew. Even the cellar was starting to smell like rotten apples. Mike turned off the water, grabbed the bucket and his supplies and ran back upstairs and outside. The cold stone of the back step chilled his feet, but he didn't let that stop him, just sat down to scrub the mess off. Once his legs looked clean, Mike dried them on an old ripped towel, then dumped the stained socks into the pail, swishing them around to loosen the worst of the muck.

"Hey there, Michael."

Mike looked up to see Grandpap marching across the backyard toward him with his fishing pole over one shoulder. A couple of ugly mud-brown river catfish dangled from a string in his hand. Mike wondered what sort of mood the old man would be in today.

"What you doing, kid?" Grandpap asked, stopping near the step. "And what's that smell? You smell like a cider press."

Good, Mike thought. Grandpap's making sense. It must be one of his good days. "A kid I know, he threw apples at me."

"Got you in the legs, did he? Must have pretty good aim. You get him back?"

"I chased him and I caught him too . . . ," Mike began.

"You scrubbing those socks to help your mother out? Or to keep from getting in trouble?" Grandpap's dark eyes gleamed.

"Both, I guess."

The old man chuckled. "Smart boy. You didn't throw apples, did you? Hard times like we're having, it's a sin to waste good food. Lots of folks are going without."

That wasn't news. It was 1933 and the whole country was suffering from what the newspapers were calling the Great Depression. From New York to California, men were out of work and their families were going hungry. It was a tough time to be in the food business, Mike knew. The family business, Costa Brothers Fine Foods, hadn't folded yet but it sure wasn't raking in mountains of moolah these days.

"Well?" Grandpap asked. "Did you throw apples or not?"

Mike shook his head. "No, sir. I know better than to waste food. I just popped him one with my fist." He went back to soaping his socks.

"Good for you, Michael." Grandpap set down his fishing pole and reached into his pocket for the knife he used to clean fish. "Scrub your shoes off too," he said. "So you won't muck up your mother's clean floors."

"Yes, sir." I'd like to mop the floors with Andy Simms, Mike thought. I'd mop so hard, Mom's floors would shine for a month. And good old Simms, he'd be waterlogged.

". . . Well, boy, what do you say?"

Darn it. Grandpap was looking at Mike as if he expected an answer to a question. Mike hadn't been paying attention, so he didn't know whether he'd missed the question or Grandpap was having one of his forgetful spells.

"What do I say about what?" He shoved his dark hair back from his face.

"My fish, of course. Caught a couple nice ones. Plenty to share. Shall I have your mother fry up some for you?"

He really didn't need this, not on top of Simms. Mike looked down at the pile of fish guts at Grandpap's feet and tried to decide whether Grandpap was joking or the old man really didn't remember that Mike hated fish, especially those nasty-looking, long-whiskered river cats.

A laugh from Grandpap, then a sharp elbow in the ribs told Mike that Grandpap was joking. Okay, this really was a good day.

Mike wrinkled up his nose. "No thanks, Grandpap. You can keep your ugly catfish. I don't eat anything with whiskers. Besides, those fish stink worse than my socks and shoes." He picked up the left shoe and swiped at it with his soapy rag.

Grandpap laughed again. "Tell you what, once you wash off all the mess, dab a little kerosene onto a rag and mix it with shoe polish. That will kill off the smell and your shoes will look as good as new. Nobody will suspect a thing." The old man winked. "Tough guys like us, we gotta stick together."

Mike grinned and winked back. "Thanks."

"You're welcome. And when you get a chance, get rid of this garbage for me, will you?" Grandpap stood and pointed toward the fish heads at his feet.

"Yes, sir." Mike would have to hold his breath to clean up the fish mess, but it was worth it for Grandpap to be in such a good mood. He was like his old self, teasing and joking, Mike realized. That had to be a good sign.

Grandpap carried his cleaned fish into the kitchen as Mike finished wiping off his shoes.

Holding his breath, Mike shoveled Grandpap's mess onto a thick newspaper and studied the bloody fish heads and guts. Nasty, he thought. How could anybody eat fish, especially after cleaning them?

He was bending to fold the newspapers into a tight bundle when an idea crept into his mind, sneaky as a rat. Those fish guts kinda looked like a present, wrapped up nice in newspaper. And by tomorrow they'd be plenty ripe. They'd smell ten times worse than rotten apples.

Do I dare? Sure, I'll do it, he decided, tucking the package between a rock and the back fence. Happy birthday to you, Andy Simms.