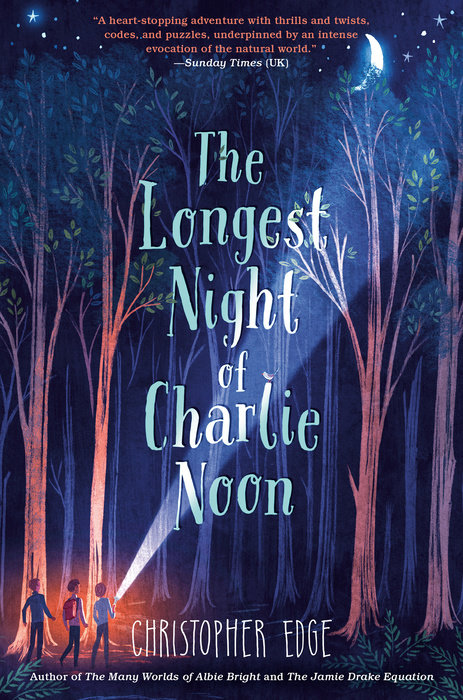

The Longest Night of Charlie Noon

Author Christopher Edge

The Longest Night of Charlie Noon

This heart-pounding mystery-adventure follows three kids who get lost in the woods at night and experience something they cannot quite explain.

Secrets, spies, or maybe even a monster . . . what lies in the heart of the woods? Charlie Noon and Dizzy Heron are determined to find out. When their nemesis, Johnny Baines, plays a prank on them and night falls without warning, all three end up lost in the woods, trapped in a nightmare. Unforeseen dangers and impossible puzzles lurk in the shadows. Like it or not, Charlie and Dizzy must work with Johnny if they are to find a way out. But time can be tricky. . . . What if the night never ends?

An Excerpt fromThe Longest Night of Charlie Noon

1

Johnny Baines says there’s a monster in here. Dizzy thinks it might be a spy. But as I scramble up the grassy bank of bluebells at the edge of the woods, it’s hard to believe there could be anything bad here at all.

Sunlight filters through the trees, bathing the grassy path ahead in shifting patterns of brightness. The faint breeze whispering through the leaves makes their shadows flicker like ripples on an imaginary river that’s following the path through the woods.

Dizzy’s already striding along, his hiccupping walk making it look like he’s forever on the verge of falling over.

“It’s this way, Charlie,” he says, glancing back to beckon me on. “That’s where I saw the first one.”

I nod, but I’m in no real hurry to catch up with Dizzy yet. This is the first time I’ve been into the woods, and for a moment, I stand absolutely still, slowly filling my senses with this place.

From the back of our school the woods look close enough to touch, a solid bank of forest green that fills…

1

Johnny Baines says there’s a monster in here. Dizzy thinks it might be a spy. But as I scramble up the grassy bank of bluebells at the edge of the woods, it’s hard to believe there could be anything bad here at all.

Sunlight filters through the trees, bathing the grassy path ahead in shifting patterns of brightness. The faint breeze whispering through the leaves makes their shadows flicker like ripples on an imaginary river that’s following the path through the woods.

Dizzy’s already striding along, his hiccupping walk making it look like he’s forever on the verge of falling over.

“It’s this way, Charlie,” he says, glancing back to beckon me on. “That’s where I saw the first one.”

I nod, but I’m in no real hurry to catch up with Dizzy yet. This is the first time I’ve been into the woods, and for a moment, I stand absolutely still, slowly filling my senses with this place.

From the back of our school the woods look close enough to touch, a solid bank of forest green that fills half of the horizon. When we set off I thought it would only take us ten minutes to get here, but I hadn’t reckoned on the strange zigzagging path that Dizzy took, following the edges of the fields that lie between the village and the woods.

Most of the time we didn’t even seem to be walking in the right direction, turning right, then left, then right again, before taking a long detour around the farmhouse that marks the halfway point between the village and the trees. But when I asked Dizzy why we couldn’t just walk in a straight line, pointing out the farm track that led to the corner of the woods, he shot me an anxious look.

“You’ve not met Mr. Jukes, who owns the farm, have you?”

I shook my head. We only moved here from London a couple of months ago. It all happened so fast. Dad lost his job and then Granddad Noon died, leaving us his house in his will. That’s when Mum and Dad decided to escape from the city and move back to this tiny village where Dad grew up. I didn’t get a say. I just had to do what I was told. I used to have friends in London, but now all I’ve got is Dizzy.

“He’ll fetch the police if he catches you trespassing on his land,” Dizzy warned me, casting a nervous glance in the direction of Jukes’s farm. “Or set his dog on you.”

From behind the long barn came the sound of an angry bark. That was all I needed to hear to make me hurry up. I didn’t want to get bitten by some mangy farm animal. I’d probably catch rabies and die. The one thing I’ve learned since we moved here is that the countryside’s full of germs.

So when we finally reached the edge of the woods, scrambling up the bank and out of sight of the farm, I breathed a sigh of relief. I say a sigh of relief, but it was actually more of a gasp, as the walk had left me completely out of breath. All week the weather’s been blazing hot, but this is the hottest day yet. It’s not even June, but on the news they said if the summer carries on like this, it’ll be the hottest since record keeping began.

All I want to do is stop and catch my breath, but Dizzy is still striding ahead.

“Come on,” he calls out again.

Dizzy isn’t Dizzy’s real name, by the way. It’s actually Dylan, but everyone calls him Dizzy, even our teacher, Miss James. She says it’s because he’s got a headful of sky, always staring out the classroom window as he watches the birds fly by.

But right now Dizzy’s gaze is fixed firmly to the ground as his lolloping walk takes him deeper into the woods. Not wanting to be left behind, I hurry to catch up.

Trees line the sun-dappled path like sentries, their serried ranks stretching as far as my eye can see. Between the broad trunks I glimpse snatches of purple, white and yellow from the waves of wildflowers that carpet the woodland floor. The air feels warm under the overhanging branches, and the mossy grass puts a spring in my step as I finally catch up with Dizzy.

“So what exactly are we looking for?” I ask.

“A sign,” Dizzy replies, glancing up from the path. “Just like I told you I saw.”

Dizzy comes to the woods every day after school. He says he’s got this special place where he sits to sketch the birds that nest here. Before we moved to the countryside the only birds I ever saw were the pigeons in the park. Flying rats, Dad called them. But the back of Dizzy’s schoolbook is filled with drawings of more birds than I even knew there were. Woodpeckers, willow warblers, blackcaps and song thrushes. Dizzy’s teaching me their names, pointing them out when they flit overhead as we sit at the edge of the school field.

That was where we were today when he told me what he’d found in the woods. The rest of the class were playing rounders, and I was supposed to be keeping deep field, but I’d gotten bored because nobody was hitting the ball in my direction, so I’d sat down on the grass next to Dizzy.

Dizzy doesn’t have to play games because he caught polio when he was little and it made one of his legs shorter than the other. This means Miss James just lets him sit and watch us play, but he spends most of his time drawing birds instead. That’s what he was doing when I sat down next to him.

“What are you drawing?” I asked.

“Shhh,” Dizzy replied, motioning with his pencil toward the fence at the end of the field.

Following the direction of his pencil tip, I looked up to see a plump reddish-brown bird perched on the fence’s top rung.

“What is it?”

“Shhh!” Dizzy whispered again, frowning as he put his pencil to the page. “It’s a nightingale.”

Keeping my mouth shut, I watched as Dizzy drew, his pencil strokes bringing the bird to life on the page of his exercise book: the thin curve of its beak, the black bead of its eye, the scaly lines of the feathers on its wings kept folded close to its side. It was as though Dizzy could see the shape of the nightingale hidden on the page and was just tracing this invisible outline.

And then the nightingale sang.

It opened its beak wide, and a rich stream of whistles and trills burst out into the sky. I stared at the nightingale, astonished. Another flurry of notes rang out from its beak, even faster than the first--this liquid melody quickly rising to a crescendo. Then the nightingale fell silent, its head bobbing from side to side as if the bird was searching for a reply. But all I could hear was the scratching of Dizzy’s pencil.

I glanced down at his drawing of the bird, the nightingale now still on the page, but when I looked up again all I saw was a sudden blur of movement, the real nightingale’s wings beating against the sky as it wheeled toward the woods.

Dizzy lifted his face to the sun as he watched the nightingale soar. As it disappeared into the green of the trees, he turned toward me.

“I found something in the woods last night.”

Even though the nightingale had flown, Dizzy kept his voice low, as if confiding a secret. From the other end of the field came a distant chorus of “Catch it!” followed by a ragged cheer, and I had to shuffle closer to hear exactly what Dizzy said next.

“I think it might’ve been left by a spy.”

As soon as Dizzy mentioned the word “spy,” a picture jumped into my head of the books Dad used to keep on a shelf in the hallway of our old house: The Secret Agent, The Riddle of the Sands, The Thirty-Nine Steps and The Valley of Fear. I don’t have any books of my own, so I used to sneak those stories off the shelf when Dad wasn’t looking and take them up to my room. Then, when I was supposed to be asleep, I’d bury my head under the covers to read them with a flashlight, taking shelter in their tales of foreign spies and sinister crimes as I tried to ignore the angry words thudding through the walls as Mum and Dad argued downstairs.

“What did you find?” I asked Dizzy, my brain already filling with thoughts of secret documents and stolen gold.

Closing his exercise book, Dizzy looked at me solemnly.

“Sticks,” he said, “on the path through the woods.”

I couldn’t stop myself from laughing.

“Dizzy--it’s the woods. Of course there’re sticks dropped on the path. What’s so strange about that?”

Dizzy’s cheeks seemed to darken slightly, his light-brown skin taking on a coppery hue.

“These sticks weren’t dropped,” he said, stuffing his exercise book back inside his school bag. “They were arranged.”

“What do you mean ‘arranged’?” I asked, still puzzled as to why Dizzy thought a spy was leaving sticks in the woods.

“They were laid out in patterns,” Dizzy replied, pushing his school bag to one side. “Some pointing like arrows, others arranged into squares, like a sign. I couldn’t help but notice them. Every stick looked exactly the same--all smooth and white--with the bark stripped off each one. The patterns they made looked like some kind of secret code, just like a spy would use.”

That got my attention. Since we moved into Granddad’s old house, the only book I’ve found to read is one that was left on the shelf in my new bedroom. It’s called Scouting for Boys and I think it used to belong to my dad. It’s all about the skills you need to be a Boy Scout, like making fires and following tracks. In it, there’s this story about how some soldiers left secret messages near landmarks like trees to keep them hidden from the enemy. Maybe that’s what Dizzy has found.

“Where exactly did you see this?” I asked.

“If we went into the woods after school I could show you,” Dizzy said. “Maybe together we could work out what the secret message means.”

“What secret message?”

The sound of Johnny Baines’s voice caused Dizzy’s face to freeze in fear. Then Johnny thudded down on the grass between us, his sudden arrival forcing me to shuffle out of the way of his sharp elbows.

“What message?” Johnny asked again, grabbing hold of Dizzy’s bag and tipping its contents onto the grass as if thinking he’d find the answer there. He leaned forward, his broad shoulders hunched as he started to pick through Dizzy’s possessions: schoolbooks, pencils and pens, a pair of binoculars and a pocket flashlight. Johnny threw them all to one side, not caring where they landed.

“Hey!” I called out indignantly.

But Johnny just ignored me, turning instead toward Dizzy, who was already cringing in anticipation.

“Come on, birdbrain. Spit it out. What are you hiding from me?”

“I--I found something in the woods,” Dizzy stammered, his words stumbling over each other as if frightened to go first. “There were these sticks laid out on the path--all arranged into shapes in some kind of code. Charlie and I are going to find it again after school. I--we--think it might be a secret message that’s been left by a spy.”

Johnny screwed up his eyes, squinting into the sun as if trying to decide if Dizzy was telling the truth. Then he laughed out loud.

“That’s not a spy,” Johnny said, turning toward me with a creepy grin that made my stomach turn. “That’s Old Crony.”

I wanted to tell Johnny to get lost and leave us alone. I can talk to him like that, even though he’s bigger than me. Everyone says Johnny Baines is the toughest kid in school, but he doesn’t scare me.

However, there was something in Johnny’s know-it-all tone that stopped me from telling him to sling his hook straight away.

“Who’s Old Crony?” I asked instead.

Behind Johnny, Dizzy had started to shove his stuff back into his bag. At my question he looked up in alarm, his eyes silently pleading with me to make Johnny go away. But Johnny just stretched his legs out, making himself more comfortable as he started to explain.

“Old Crony lives in the woods. Deep in the heart of the woods. He’s been there for years. He’ll be the one that’s left that message, not some stupid spy.”

Beneath the dark line of his close-cropped hair, Johnny’s eyes shone with a strange fascination.

“Old Crony eats children, you know.”

Dizzy flinched.

“Any kids that cross into his territory are fair game for eating,” Johnny continued, his words laced with a grisly delight. “My dad told me that. He says he used to leave any scraps of meat he couldn’t sell at the edge of the woods to keep Old Crony quiet.”

Johnny’s dad runs the butcher’s shop in the village. That’s why Johnny’s sweat stinks of sausages. I think all he ever eats is meat. But he’s not scaring me with this fairy tale.

“That’s rubbish,” I said scornfully. “If Old Crony is real, where does he live? In a house made of gingerbread in the middle of the woods?”

“No,” Johnny replied, cocking his head as he fixed me with a dead-eyed stare. “He builds his house out of the bones of the children he catches. Right after he boils them up. Old Crony left those signs to lure you deeper into the woods. I reckon you’re next for the pot.”

I didn’t blink as I held Johnny’s stare, wanting to show him that he didn’t scare me.

“You’re making it up.”

“How do you know?” Johnny hawked up phlegm and spat a dirty yellow globule onto the grass near my feet. “You’ve only been here for five minutes. My family’s lived here for hundreds of years. We know stuff about the woods. More than you and birdbrain here could ever know.”

From across the field came a shrill blast. At the sound of the teacher’s whistle, Johnny slowly pulled himself to his feet. He stared down at me, his stocky frame blocking most of the sun.

“If you go into the woods, Old Crony will get you,” he said. “You just see.”

I glance up now at the maze of branches overhead, scraps of blue still visible between their patchwork of leaves. Then I drop my gaze to the grassy track, cobbles of light and shade marking the path between the trees as Dizzy leads us on.

That’s what we’re doing. We’re going into the woods.