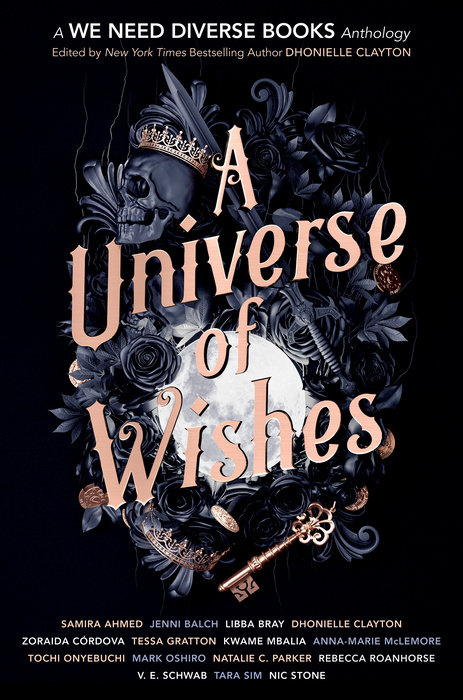

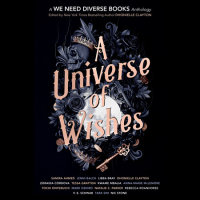

A Universe of Wishes

Edited by Dhonielle Clayton

A Universe of Wishes

From We Need Diverse Books, the organization behind Flying Lessons & Other Stories, comes a young adult fantasy short story collection featuring some of the best own-voices children's authors, including New York Times bestselling authors Libba Bray (The Diviners), V. E. Schwab (A Darker Shade of Magic), Natalie C. Parker (Seafire), and many more. Edited by Dhonielle Clayton (The Belles).

In the fourth collaboration with We Need Diverse Books, fifteen award-winning and celebrated diverse authors deliver stories about a princess without need of a prince, a monster long misunderstood, memories that vanish with a spell, and voices that refuse to stay silent in the face of injustice. This powerful and inclusive collection contains a universe of wishes for a braver and more beautiful world.

AUTHORS INCLUDE: Samira Ahmed, Jenni Balch, Libba Bray, Dhonielle Clayton, Zoraida Córdova, Tessa Gratton, Kwame Mbalia, Anna-Marie McLemore, Tochi Onyebuchi, Mark Oshiro, Natalie C. Parker, Rebecca Roanhorse, V. E. Schwab, Tara Sim, Nic Stone

An Excerpt fromA Universe of Wishes

A Universe of Wishes

Tara Sim

He had taken to making wishes whenever he could.

At the last morning star, on the edges of tarnished coins, along the cracks of bones that split in fires.

It was never enough. No matter how often or how aggressively he wished, his words were never heard, his pleas went unanswered.

And then one day, he learned why: wishes could not be made on innocent things, innocuous things, like stars and coins and clovers.

Because wishes were granted only by the dead.

The city of Rastre was pumping like a heart, people moving through its streets as blood flows through veins. It was the end of the day, and the sun burned copper on the horizon, casting long shadows out of the spires and rooftops around him.

Thorn waited in the shadow of a cathedral’s bell tower, crouched on the slanted roof with his arms braced on his knees. The wind blew, and he huddled deeper into his threadbare jacket. He’d have to get a new one soon.

Eventually the door across the street opened, emitting a tall,…

A Universe of Wishes

Tara Sim

He had taken to making wishes whenever he could.

At the last morning star, on the edges of tarnished coins, along the cracks of bones that split in fires.

It was never enough. No matter how often or how aggressively he wished, his words were never heard, his pleas went unanswered.

And then one day, he learned why: wishes could not be made on innocent things, innocuous things, like stars and coins and clovers.

Because wishes were granted only by the dead.

The city of Rastre was pumping like a heart, people moving through its streets as blood flows through veins. It was the end of the day, and the sun burned copper on the horizon, casting long shadows out of the spires and rooftops around him.

Thorn waited in the shadow of a cathedral’s bell tower, crouched on the slanted roof with his arms braced on his knees. The wind blew, and he huddled deeper into his threadbare jacket. He’d have to get a new one soon.

Eventually the door across the street opened, emitting a tall, slender boy who couldn’t be much older than he was. The boy closed the door behind him, locked it, and headed toward the eastern sector.

Thorn waited several minutes to be sure. When the sun had bled fully into the earth, the sky deepening into a two-day bruise, Thorn slid to the edge of the roof. Jade lanterns flickered to life, casting Rastre in a glowing, starry light.

That light didn’t reach the street below. Thorn hopped down into that welcome darkness. Beyond he could hear the sounds of passersby, a child screaming in delight, the tinny first notes of a street musician.

Thorn popped the collar of his jacket and crouched before the door. He tickled the lock with his pick until it gave way and he could slip inside.

His breathing was loud in the silence that greeted him. Thorn swallowed and willed his heart to slow. He usually prowled the cemetery in the western sector, but one too many close calls with the groundskeeper had made him leery enough to try another approach. That, and he was getting tired of constantly washing grave soil out of his clothes and from the beds of his fingernails.

Not like this was much better--but at least it was cleaner.

The building was modest in size, large enough to contain two stories. The ground floor was used for receiving and accommodating customers. Upstairs was a collection of coffins and caskets.

But he knew, after a week of observation and more than his fair share of peeking through the window, that there was actually a third story. It was just underground.

Thorn moved past an open display coffin and a reception desk, around to the back, where a smaller desk sat covered in papers and parchment and pens. And animal figurines, of all things. Beyond that stood a door, and jiggering the lock rewarded him with a waft of cooler air.

A familiar eagerness filled his belly, the taste of magic already on his lips. He licked them and crept down a wooden staircase, feeling his way through the dark until he found a jade lantern at the bottom. It flared to life when he tapped it, illuminating a couple of autopsy tables and a rack of tools that could have doubled as torture devices.

And rows and rows of crystal capsules.

That was what gave off all this cold. Crystals were used for storing perishable goods, or keeping houses cool in the height of summer . . . or keeping dead bodies fresh.

Thorn approached the nearest capsule. They were built into the wall like drawers. He fumbled with the frozen handle until he could yank it open, pulling out the capsule’s sole occupant.

The man was waxen and stiff. His skin had become a light blue. Thorn had heard people speak of the dead, had heard words like sleeping and peaceful, but this man didn’t fit either of those. He seemed troubled even in death, his thick eyebrows lowered over sunken eyes, his mouth flat and unimpressed.

Thorn paused, looking at the freshly sutured Y-shaped line running down the man’s naked belly. He wasn’t used to this. Touching the dead, yes; digging up bodies, yes. He’d grown accustomed to the smell of earthy ozone and decay, the creeping mold and mulch of graveyards, the chill of stone and nights without moonlight.

This, though, was something altogether different. This was clean and clinical. It was crystal and chalcedony.

It was . . . wrong.

Thorn took a deep breath. He felt that breathing was somehow disrespectful, standing above a body that was no longer capable of the task. And what a strange concept, for this man to have existed only between the span of two breaths--his first and his last--to become merely a thing.

Well, there was still something inside him. And that was the whole point.

Thorn took out his pocketknife and flipped it open. It gleamed in the jade light, deceptively clean despite its grisly purpose. He ran the knife over the autopsy incision, popping sutures and unraveling flesh. Much easier than hacking his way through dead tissue and muscle.

He peeled back the man’s skin, exposing a torso that had been hollowed out like a pumpkin. The organs had been detached and taken . . . somewhere. Thorn didn’t want to know, and didn’t care. Instead, the man’s body was lined with cotton, as if he were being turned into some sort of morbid doll.

His ribs were still there, however. They curved up like anxious smiles, or the claws of some forgotten beast.

And there, residing between the fourth and fifth rib on his left side, was what Thorn had come here for. It was invisible, but he felt it, a tiny swirling galaxy of potential. It drew him in like a promise. A secret.

Thorn took the obsidian from his pocket and held it against the man’s ribs. The little galaxy continued to swirl between his bones, confused and directionless, but the lure of the obsidian finally caught its attention. It seeped into the black, glassy rock, joining the other little galaxies Thorn had already taken. His own pocket-sized universe.

He wondered if he finally had enough. But maybe, just to be sure, he should--

“What are you doing?”

Thorn whipped around. Standing at the bottom of the stairs was the boy he’d seen leaving the funeral parlor.

He had only a moment to take him in: skin a couple shades browner than his own, hair dark and curling at the ends, eyes that were the gray-green hue of moss. They were wide and spooked, darting between Thorn and the inelegantly opened corpse.

Thorn shoved the obsidian back into his pocket and did the only thing he could think of: he pushed the man’s body off its crystal slab.

The boy cried out in dismay and hurried forward to fix the mess. Thorn took his opening and darted for the stairs, his boots thundering on the wooden planks. He crashed into the desk up above, rattling the little animal figurines on its surface.

He was almost to the front door when a hand clawed at his shoulder. Thorn twisted and reached for his pocketknife, but the boy was stronger than he looked, and one purposeful shove made Thorn stagger farther into the shop. The backs of his knees caught the edge of something, and he fell, landing with a hard thud that winded him.

The lid to the display coffin fell shut on top of him.

Panic welled in his throat. Thorn dropped his pocketknife and banged on the lid, shoving his shoulder against it, but it wouldn’t budge. A creak above told him the boy was likely sitting on top of it, his weight rendering the lid unmovable.

“Who are you?” the boy demanded, voice muffled through the wood.

Thorn didn’t answer. He was breathing fast; the coffin smelled like cedar and linseed oil, and something herbal--maybe rosemary. He tried pushing the lid again, but it gave only a mere centimeter.

“How dare you come in here and deface the dead,” the boy went on. “You realize that brings bad luck, don’t you?”

Thorn was surprised by the rasping laugh that escaped him. “I’m used to bad luck.”

Silence. He could hear his own heart pounding, as if his body wanted to assure him that he was alive, despite his immediate surroundings.

“I’m not going to let you out until you explain yourself,” the boy said after a moment. “Poor Mr. Lichen didn’t deserve what you did to him.”

Thorn was inclined to agree, but he could still feel the little galaxy in his pocket, and he didn’t regret it. He couldn’t say that, though; he’d never be released from this wretched coffin if he did.

When Thorn didn’t reply, the boy drummed his fingers against the lid. “If you don’t explain yourself,” he said softly, almost too softly for Thorn to hear, “I’ll call the city guard.”

Dread pooled in his chest. He’d been evading the guard for two years; he couldn’t allow all his hard work to unravel in a single night.

But he couldn’t easily explain what he’d been doing either.

“I . . .” His face flared hot, though the rest of him burned cold. “I was harvesting magic.”

The boy above him was silent. Thump thump went Thorn’s heart, and Fool, fool went his mind. He worried his lower lip between his teeth and blurted: “It’s for wishes. This magic, it’s not something people understand, so they can’t access it while they’re alive. So it just stays inside them, even after they die. It’s a waste. So I . . . I was collecting it from the bodies. For wishes. It’s what I do.” Then softer, pleading: “Please let me out.”

More silence. Thorn’s breaths were absorbed by the coffin walls. Finally, the boy slid off the lid and opened it. Thorn blinked at the moonlight that spilled through, staring up at the morgue boy. His expression was a slurry of confusion, annoyance, and fascination.

Thorn wondered if it was enough to win his freedom. But then the boy said, almost imperially, “Prove it.”

Thorn blanched. His hand twitched toward his pocket. “Why? Why should I waste a wish on you?”

The boy’s eyebrows rose. “There’s a guard patrol just around the corner, you know. They should be able to hear me shout for help.”

Thorn grimaced, sitting up. “That won’t be necessary.”

“Oh, good.” The boy smiled, and it offset a dimple on one side, a perfect little divot in his cheek. He stepped back to allow Thorn to climb out of the coffin, reversing his momentary death.

“What’s your wish?” Thorn grumbled.

The morgue boy thought, running a hand through his thick, dark hair. His gray-green eyes took in Thorn’s own hair--white, like snowfall and ash, like starlight on water. A rarity in Rastre, when most sported hair in darker shades.

The boy snapped his fingers and gestured for Thorn to follow him. Thorn glanced at the front door--too far to make a run for it, especially if what the boy had said about the patrol around the corner was true--and followed him to the desk in the back of the shop. The morgue boy picked up one of the ceramic animal figurines. It was of a little tiger, painted orange with black stripes, its eyes shining jet.

“Make it come to life?” The boy phrased it like a question, almost shy about it.

Thorn frowned. “I can’t make it live.”

“No, no--I meant make it sentient. Make it move.”

All that hard work to get a wish, and the boy was going to waste it on this? Thorn sighed and rubbed his face, eyes gritty from lack of sleep, hands smelling like Mr. Lichen’s clammy skin.

But then a thought occurred to him, and it was like opening a basement door into sunlight.

“I have a proposition,” Thorn said.

The morgue boy tilted his head slightly. “Are you really in a position to be making one?”

“Look--I need a way to harvest wishes, and you obviously want some of your own. So how about we strike up a deal? I get to come here at night and take the magic from these bodies, and in return, you get three wishes from me.”

The boy’s eyes widened, whether greedy at the idea of more wishes or stunned by the outlandish request. Maybe both. He looked at the figurine in his hand, turning it around in his fingers. “Would this count as one of those three wishes?”

“Yes.”

The boy thought some more, biting his lower lip. Finally, he sighed.

“If you make this wish come true,” the boy said, holding up the figurine, “then yes.”

Thorn smiled in victory. He slipped the obsidian from his pocket and felt the dance of magic inside, his prized universe of wishes, a handful of potential and possibility.

He pulled on a thread of magic, teasing it from its swirling shape and out through the glassy rock. He wrapped that thread around the little figurine, never taking his eyes off it. His lips moved soundlessly, crafting the shape and size of his wish, the parameters of its probability. The magic flared, no longer dormant as it had been between Mr. Lichen’s ribs, but glowing now with purpose.

The boy gasped as the figurine stretched like a housecat and sat back on its haunches in the center of his palm, looking up at him as its striped tail swished from side to side. He lifted it to his eyes and grinned, a world of amazement on his face. Wonder, Thorn realized, was beautiful; it banished what was impossible and made room for belief. When he thought about it, he supposed that could very well be a force stronger than most things--even wishes.

He met Thorn’s gaze with all the weight of that wonder. Thorn felt a quiver of it in his chest, and it was warm.

The boy held out his hand, the one not holding the tiger. Thorn hesitated, then took it in his own. They shook.

“Welcome to Cypress’s Funeral Parlor,” the boy said.

The boy’s name was Sage. His family owned the parlor, and he’d grown up among coffins and caskets, scalpels and forceps, crystals and incense. The dead did not bother him. In fact, they were considered something sacred, making Thorn’s treatment of poor Mr. Lichen all the more atrocious. Sage made him help stitch the body back up and return it to its capsule before he was allowed to leave for the night.

But Thorn returned the next night, and Sage was waiting for him. The little tiger prowled on his shoulder, occasionally batting at a curl of his hair.

“How many wishes do you have stored in that thing?” Sage asked, referring to the obsidian.