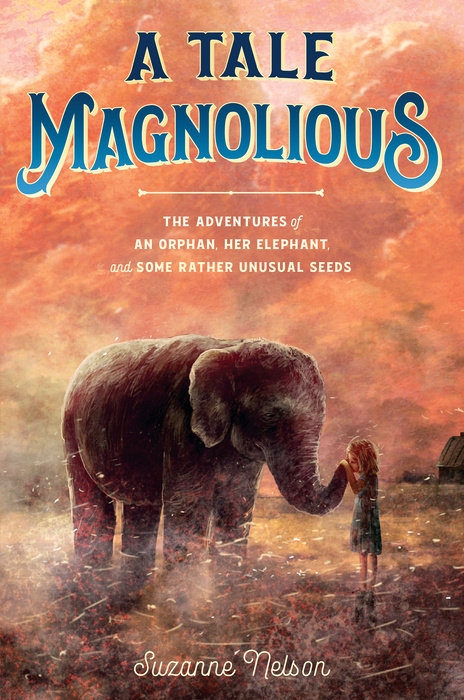

A Tale Magnolious

Fans of Kate DiCamillo and Katherine Applegate will warm to this story of an orphan and an elephant who band together to save a lovelorn town, relying on an eccentric crew and a couple of miracles along the way.

Nitty Luce is an orphan--and a thief. Magnolious is an elephant--and a fugitive. When the two misfits come face to face in the middle of a blinding dust storm, they form an immediate bond.

But with Nitty hiding a stolen pouch of gleaming green seeds and Mag mere moments from being hanged, the two don't have much time to get to know each other. Escaping into the storm, they end up on a barren farm in Fortune's Bluff, a town withered by a decade of dust storms. While most would be deterred by the farm's curmudgeonly owner, Windle Homes, Nitty sees past his harsh exterior. She promises to bring the farm back to life--with the help of Mag and those little green seeds.

Soon enough, Nitty and Mag are harvesting their first crop, and they're quickly the talk of the town. But as the townspeople become hopeful, the Mayor Neezer Snollygost becomes suspicious.

Will Nitty and Mag be able to save Fortune's Bluff and make a new, safe home for themselves? Doing so might just take a miracle. . . .

An Excerpt fromA Tale Magnolious

Nitty Luce wasn’t born a thief. She wasn’t born to rescue elephants. Or to make miracles. Nobody ever told her that, though, so she never had reason to doubt. If she’d doubted, none of the bamboozling goings-on in Fortune’s Bluff that spring might ever have happened.

But they did happen.

The morning started much like any other, with Nitty’s empty stomach. It was near on two weeks since she’d run away from Grimsgate Orphanage, two weeks fighting pigs for the slop in their troughs and waiting for breadlines to empty out to scrounge a few dropped crumbs. She wouldn’t stoop to begging, not after Headmistress Ricketts’s stories of police tossing street urchins into lockup. Just yesterday she’d caught sight of her reflection in a store window, and oh, was she a shambles! Her tumbleweed hair poked out in all directions, crispy with days-old dust. There was a film over her sun-toasted skin and her flour-sack dress, so in the glass she appeared more as a dirt smear than a ten-year-old girl.

“You’ll bunk in prison with the likes of Cutthroat Cob,” Miz Ricketts had told them at the orphanage. She always gave this sinister warning before lights-out, in case any of her wards got ideas about running away at night. “Or worse, Fang-Toothed Lou.”

Nitty didn’t believe a word of it. At least, not during daylight hours. Still, she didn’t like the idea of fangs of any sort, so whenever she caught sight of police officers, she kept her distance.

But this particular morning, she was doing battle with her hunger again, and it was being a downright bully. When she wandered into the heart of a city, a solid piece west of Grimsgate and north of nowhere, she was too light-headed to worry over police. In fact, on reading the poster nailed to a lone withering tree on Main Street, Nitty had to steady herself against a nearby lamppost.

Come one, come all!

Witness the death of a murderous four-ton beast!

Public hanging in the square at high noon

A Gusto and Gallant spectacle never to be forgotten.

Below the words was a gruesome cartoon drawing of a circus elephant trampling a man, with a small caption: great magnolious kills trainer in cold blood.

Nitty leaned closer, studying the fangs and claws drawn on the elephant, the steam pouring from its mouth and trunk, the smoldering rage in its eyes. The picture was nightmarish, the sort of sensational rubbish Miz Ricketts loved to read about in the Daily Tattler. Nitty didn’t think too harshly of the Tattler, though. In fact, she often rescued old editions from the fireplace before they became kindling. They offered the most entertaining reading at Grimsgate.

Now the crowd gathered about the poster was nodding and whispering, heads bobbing like the wind-up tin clowns Nitty had once seen in a toy shop.

“Savage business,” one man declared, while two young women fretted about needing to procure smelling salts before the hanging. “The Gusto and Gallant Circus is well rid of the monster. I feel its devilry in my very bones. It would kill again, mark my words.”

“Yes,” one woman twittered. “I heard its eyes are red as Beelzebub himself.”

Nitty frowned. What did these people know about this elephant? Not a speck more than she did, probably. She’d never seen an elephant before, and she doubted any of them had either. She’d once read an account of an elephant in the Tattler, a “Just So” story by a man named Rudyard Kipling, that said the animals had an “insatiable curiosity.” “Insatiable” made her think of eating chocolate, which would be delicious and wonderful, if there were any chocolate to be had. Which there was not. But if “insatiable” made her think of the delicious and wonderful, then an elephant’s curiosity must be those things as well.

Elephants must surely be like orphan girls, she decided: creatures sorely misunderstood and blamed for a host of troubles they had nothing to do with.

She nudged her way through the crowd, glimpsing food carts and tinkers’ wagons lining the edges of the square. A barbershop quartet sang at one corner while a clown at another sold balloons. The square had the jaunty atmosphere of a carnival, which seemed even worse than backward to Nitty, given the occasion—especially once she spotted a towering crane rising up from its center. The crane, she guessed, was how they meant to hoist Magnolious from her feet. It was every kind of awful. A chain fashioned into a noose hung from its arm, swaying as a forceful gust of wind hit it.

Nitty shielded her eyes from the grit blasting her face, and others around her held kerchiefs to their mouths and scanned the sky. They were worrying over a dust storm, waiting for the telltale mud-colored clouds to barrel down on them with the force of a bison stampede.

Nitty held her breath, scoping for alleyways where she might take shelter, but the gust soon wheezed out.

She turned away from the crane. She wouldn’t watch the hanging, a gawker like the rest. It would be too cruel. But—her stomach whined at wafting scents of roasted peanuts and cotton candy—she would stay close by, in case somebody spilled popcorn or dropped one or two precious peanuts. Most any food had a sandy aftertaste these days anyway, so it wouldn’t much matter if she got it from the ground.

She was heading toward the peanut cart when a sudden spark of green caught her eye. She swiveled her head and spotted a wooden wagon. A slatted board in its side was propped open to display an array of colorful oddities. Puppets dangling from strings, jewel-toned bottles full of mysterious potions or exotic perfumes, glass globes holding miniature kingdoms so real-looking that Nitty half expected to see ant-sized people popping out of their cottages and castles. The sign painted along the wagon’s side read the merrythought windowshop.

Nitty stepped closer, and again a twinkle of green flashed. She traced it to a small open pouch full of the strangest objects she’d ever seen. Shaped like question marks no bigger than a fingernail, they were the greenest sight in town. Maybe in the whole county—or state, for that matter. Their bright hue was so cheerful, so incandescent, that Nitty had the urge to climb into the pouch with them.

Her heart reached out to them, rising snugly and pleasantly into her throat. Being inside that pouch would be like being in a proper jungle—a jungle so full up with trees and plants that she could wrap herself in hammocks of leaves and weave herself a home of vines. Nothing would be brown in that jungle. Even dirt and rocks would grow lovely, fuzzy moss.