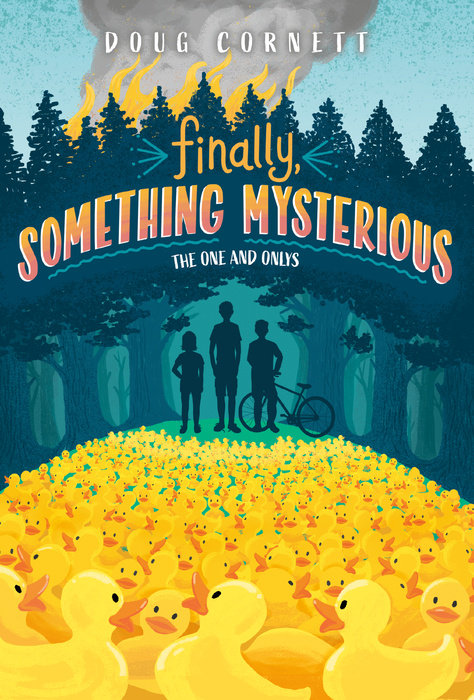

Finally, Something Mysterious

Finally, Something Mysterious is a part of the The One and Onlys collection.

The best mysteries can only be solved with your best friends. The perfect summer read for fans of Stuart Gibbs.

Paul Marconi has always thought that Bellwood was a strange town, but also a boring one. Not much for an eleven-year-old to do. Fires are burning nearby, Paul's parents are obsessed with winning a bratwurst contest, and his best friend, one of the founding members of their only-child detective club, the One and Onlys, is about to acquire a younger sister, sort of undoing their whole reason for existing. But then! Hundreds of rubber duckies have appeared on the lawn of poor Mr. Babbage without any explanation. Finally! There is something that Paul and his friends can actually investigate.

In the face of all these bizarre occurrences, Paul is convinced that uncovering who deposited the duckies will finally bring some sense to what has become an upside-down world. Soon the three friends have a long list of suspects, all with their own motives, but no clear culprit. When everything comes to a head at the town's annual Bellwood Bratwurst Bonanza, Paul discovers that some things don't have an easy explanation and not every mystery can be solved.

A perfect summer story about friends, amateur sleuthing, and a whole lot of rubber duckies.

“The perfect mix of hilarious and heartwarming—kids won’t be able to get enough of Paul and his friends’ Bellwood adventures.”—Elsie Chapman, author of All the Ways Home

"Delightful fun for budding mystery fans."--Kirkus

"A diverting mystery with clever misdirection that will keep readers guessing until the end."--The Bulletin

"The quirkiness of the premise and the light, punny humor give the narrative its momentum."--Booklist

"The One and Onlys seem primed to become a popular trio among readers who enjoy an old-fashioned whodunit."--Publishers Weekly

An Excerpt fromFinally, Something Mysterious

1

The First Weird Thing

The weirdness in Bellwood all began with the smoke in the air and the ducks in Mr. Babbage’s backyard. After they showed up, a lot of other weird things started happening. Mysteries, you could call them. Some of them were scratch-your-head-and-say-hmm kind of weird, but a couple of them were big-time weird. Stare-up-at-the-night-sky-and-wonder-about-the-meaning-of-life kind of weird. And-hope-that-while-I’m-staring-up-there-a-bird-does-not-poop-on-me-cuz-that-would-not-be-a-good-sign-regarding-the-meaning-of-life. That kind of weird.

The smoke was easy to explain: a wildfire was burning in a big state forest outside of town. When the wind shifted the wrong way, all of Bellwood smelled like a campfire.

The ducks in Babbage’s yard were a different story. They appeared one seemingly normal Tuesday morning, scattered all over the grass. There must have been hundreds of them, their little yellow tails poking into the air, each duck with the same creepy look on its face: eyes wide open and vacant, like empty garages; bill curved upward in a kind of lipsticked maniac smile. I could picture the moment Babbage discovered them: he looks out at his backyard as he drinks his morning coffee, then boom—his mouth gapes open, his eyes go wonky, his coffee mug drops to the ground. Crash. Splash. Duckies? Duckies!

These were rubber duckies—the kind you take a bath with. Nobody could explain where they came from. None of his neighbors had ducks in their backyards. But Babbage’s yard? Overrun with ducks. A mystery.

News spread quickly in Bellwood. A dog could barf up an action figure on one side of town, and before it was mopped up, people would be debating the finer points of canine digestion on the other side of town. I know because that actually happened. Don’t believe me? Ask my dog, Ronald. But that’s what you get for living in such a small, out-of-the-way place. And so when rubber duckies invaded Babbage’s yard, everybody knew about it, and fast. By ten in the morning, the One and Onlys—that’s my two best friends and me—were racing our bikes up the cul-de-sacs of Bellwood, cutting through backyards, and trundling through woods, hoping to get there before the little visitors vanished.

Shanks, Peephole, and I made the crosstown trek in exceptionally good time (apologies to Mrs. Hoover’s geraniums, may they RIP) and rolled up to a clump of stupefied Bellwoodians staring at the ducks with wary eyes. Mr. Babbage’s dog, a little white yappy thing, was bouncing around the yard, growling wildly at the ducks. Officer Portnoy, who had just visited our fifth-grade classroom on the last day of school to remind us about proper bicycle safety, was talking to Mr. Babbage at the edge of the lawn. Portnoy held a duck inches from his face. It looked like they were having a staring contest. The duck was winning.

“Okay, One and Onlys,” Shanks said. “Time to gather clues. Paul, you go snoop on Mr. Babbage and Officer Portnoy. See if you can overhear anything that might be useful. Peephole and I will get a closer look at these duckies.”

I strolled over and stood behind Babbage and Officer Portnoy, trying to appear like a normal, nonsnooping kid.

“Well, Mr. Baggage,” I heard Officer Portnoy say, “I’m stymied.”

“Please, call me Lance,” Babbage said, nervously smoothing the collar of his bathrobe and shifting his gaze from his transformed backyard to the growing crowd of onlookers.

Mr. Babbage was always very well dressed, and today was no exception. His bathrobe was scarlet and silky, and it went all the way down to his feet, which were clad in slippers made of some kind of animal fur. His thin black hair was parted perfectly to one side, and his thick eyebrows seemed to be combed.

“You don’t think they’re . . . dangerous, do you?” I heard him ask Officer Portnoy, his face tight with worry.

Officer Portnoy shook his head and clapped Babbage on the back. “They’re not real ducks,” he said in a reassuring tone. “So no need to worry.”

But Babbage did look worried. He flicked his eyes back and forth to see if anybody was listening, but luckily he didn’t look down at me. He leaned closer to Officer Portnoy. He began whispering something, so I casually inched up behind them to listen.

“. . . and normally I wouldn’t pay attention to such things. It’s just that it was so vivid . . . so real. In my dream there was a horrible beast in my backyard . . . an enormous, ghastly . . . thing. . . .” Babbage’s voice was faint and wavering. “It was trying to get in my house, you see, but I wouldn’t open the door. Its breath was heavy, steady—almost like a machine. Chuk chuk chuk. The walls were rattling. And then I woke up, and I could have sworn, for a second or two, that I still heard it breathing, but faint, like it had already run away. And that’s when I looked out the window and saw . . . them.” He nodded at the ducks. “I called the police immediately—didn’t even go outside to look. I just had this spooky feeling about them. It must be some kind of sign, don’t you think?”

Portnoy shrugged, never taking his eyes off the duckies. “I’m afraid dreams are out of my jurisdiction.”

Meanwhile, Shanks had wandered into the middle of the yard and was standing among a litter of ducks, grinning from ear to ear, her arms outstretched. Compared with the ducks, and with Mr. Babbage’s dog, Shanks looked like a giant, which is maybe why she was smiling so much, because in reality she was short. Shortest-person-in-the- fifth-grade short, and unless she was planning on growing a bunch over the summer or somebody else was planning on shrinking, she’d be the shortest person in the sixth grade, too. Sometimes when we all hung out together, people mistook her for Peephole’s little sister, which Peephole thought was hilarious. Shanks didn’t.

Shanks may have been small, but her personality was big. Like right now, she was having a blast in Babbage’s backyard. Her electric-blond hair, almost white, which cascaded over her shoulders and reached down to her lower back, was swishing to and fro as she surveyed all the little yellow bodies around her. Shanks was like me: she loved mysteries.

Peephole, meanwhile, lingered at the edge of the crowd. He liked solving things, but mysteries made him uncomfortable. Actually, a lot of things made him uncomfortable: thunder, black ice, cats, leftovers, gym class, Vikings, loose tree branches that could fall on you at any time, eating outside, athlete’s foot, certain cheeses, girls, basketball, the sound of other people’s sneezes, the bubonic plague, Norwegian accents, and nose hair trimmers, to name a few. Worst of all, Peephole was afraid of bugs. And if you squinted, the duckies sort of looked like an infestation.

Babbage smoothed his collar again. “I guess I’m just on edge. This smoke”—he sniffed the air—“it’s so . . . eerie.”

Officer Portnoy clicked his tongue in agreement, then turned to the crowd with a little startle, as if these thirty or so people had suddenly snuck up on him. Not exactly the most perceptive person, especially for a police officer.

“Okay, everyone, go on home. Nothing to see here.”

Whenever there is clearly something very interesting to see, adults say there is “nothing to see.” It must be in the manuals for police officers and teachers.

Officer Portnoy noticed me looking up at him. A silence hung in the air between us. Finally, he said, “Macaroni.”

“Marconi,” I corrected him. I love mac and cheese, but I don’t want to be mistaken for it.

“Pam Macaroni.”

Oh, come on. Bellwood’s finest was not exactly Sherlock Holmes. “Paul, actually.”

“Right. So, Paul . . . are you practicing proper bicycle safety?” He grinned down at me. Or, rather, the giant mustache that almost entirely covered his mouth grinned down at me.

I thought of the poor toad sculpture in the Lombardis’ yard, the one that I had decapitated in my mad rush to get there. RIP to you, too, Mr. Toad. “For the most part,” I answered.

“Glad to hear it. Safety comes first. Always remember that. Now, Paul, there’s nothing to see—”

“Can I take one?”

Officer Portnoy seemed surprised by my question. I was, too. I didn’t know I was going to ask it until it came out.