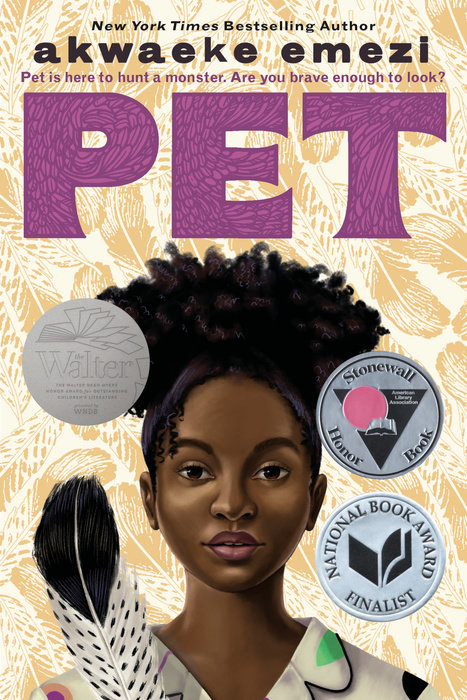

Pet

NATIONAL BOOK AWARD FINALIST • STONEWALL BOOK AWARD WINNER • ONE OF TIME MAGAZINE’S 100 BEST YA BOOKS OF ALL TIME

NAMED ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR by The New York Times • Time • Buzzfeed • NPR • New York Public Library • Publishers Weekly • School Library Journal • A KIRKUS REVIEWS BEST YOUNG ADULT BOOK OF THE CENTURY

A genre-defying novel from the award-winning author NPR describes as “like [Madeline] L’Engle…glorious.” A singular book that explores themes of identity and justice. Pet is here to hunt a monster. Are you brave enough to look?

There are no monsters anymore, or so the children in the city of Lucille are taught. Jam and her best friend, Redemption, have grown up with this lesson all their life. But when Jam meets Pet, a creature made of horns and colors and claws, who emerges from one of her mother's paintings and a drop of Jam's blood, she must reconsider what she's been told. Pet has come to hunt a monster, and the shadow of something grim lurks in Redemption's house. Jam must fight not only to protect her best friend, but also to uncover the truth, and the answer to the question--How do you save the world from monsters if no one will admit they exist?

A riveting and timely young adult debut novel that asks difficult questions about what choices you can make when the society around you is in denial.

"[A] beautiful, genre-expanding debut" –The New York Times

"The word hype was invented to describe books like this." –Refinery29

An Excerpt fromPet

Chapter 1

There shouldn’t be any monsters left in Lucille.

The city used to have them, of course—what city didn’t? They used to be everywhere, thick in the air and offices, in the streets and in people’s own homes. They used to be the police and teachers and judges and even the mayor; yeah, the mayor used to be a monster. Lucille has a different mayor now. This mayor is an angel; the last couple of mayors have all been angels. Not like a from-heaven, not-quite-real type of angel but a from-behind-and-inside-and-in-front-of-the-revolution, therefore-very-real type of angel.

It was the angels who took apart the prisons and the police; who held councils prosecuting the former officers who’d shot children and murdered people, sentencing them to restitution and rehabilitation. Many people thought it wasn’t enough; but the angels were only human, and it’s hard to build a new world without making people angry. You try your best, you move with compassion, you think about the big structures. No revolution is perfect. In the meantime, the angels banned firearms, not just because of the school shootings but also because of the kids who shot themselves and their families at home; the civilians who thought they could shoot people who didn’t look like them, just because they got mad or scared or whatever, and nothing would happen to them because the old law liked them better than the dead. The angels took the laws and changed them, tore down those horrible statues of rich men who’d owned people and fought to keep owning people. The angels believed and the people agreed that there was a good amount of proper and deserved shame in history and some things were just never going to be things to be proud of.

Instead, they put up other monuments. Some were statues of the dead, mostly the children whose hashtags had been turned into battle cries during the revolution. Others were giant sculptures with thousands of names carved into them, because too many people had died and if you made statues of everyone, Lucille would be filled with stone figures and there’d be no room for the alive ones. The names were of people who died when the hurricanes hit and the monsters wouldn’t evacuate the prisons or send aid, people who died when the monsters sent drones and bombs to their countries (because, as the angels pointed out, you shouldn’t use a nation as a basis to choose which deaths you mourn; nations aren’t even real), people who died because the monsters took away their health care—names and names of people and people, countless letters recording that they had been.

The citizens of Lucille put dozens of white candles at the base of the monuments, hung layers of marigold necklaces around the necks of the statues, and when they walked past, they would often fall silent for a moment and press a palm against the stone, soaking up the heat the sun had left in it, remembering the souls the stone was holding. They’d remember the marches and vigils, the shaky footage that was splashed everywhere of their deaths (a thing that wasn’t allowed anymore, that gruesome dissemination of someone’s child gasping in their final moments, bubbling air or blood or grief—the angels respected the dead and their loved ones). The people of Lucille would remember the temples that were bombed, the mosques, the acid attacks, the synagogues. Remembering was important.

Jam was born after the monsters, born and raised in Lucille, but like everyone else she remembered. It was taught in school: how the monsters had maintained power for such a long time; how the angels had removed them, making Lucille what it is today. It wasn’t like the angels wanted to be painted as heroes, but the teachers wanted the kids to want to be angels, you see? Angels could change the world, and Lucille was proof. Jam was fascinated by them, by the stories the teachers told in history class. They briefly mentioned other angels, those who weren’t human, but only to say that Lucille’s angels had been named after these other ones. When Jam asked for more information, her teachers’ eyes slid away. They mentioned religious books, but with reluctance, not wanting to influence the children. Religion had caused so many problems before the revolution, people were hesitant to talk about it now. “If you really want to know,” one of the teachers added, taking pity on Jam’s frustrated curiosity, “there’s always the library.”

Why can’t they just tell me? Jam complained to her best friend, Redemption, as they left the school. Her hands were a blur as she signed, and Redemption smiled at her annoyance. It was the last day of classes before summer break, and while he was excited to do nothing for the next several weeks except train, Jam was—as always—on some hunt for information.

“You’re giving yourself homework,” he pointed out.

Aren’t you curious? she replied. Who the old angels were, if they weren’t human?

“If they were even real, you mean.” Redemption adjusted the strap of his backpack. “You know that’s what a lot of religion was, right? Just made-up things used to scare people so they could control us better.”

Jam frowned. Maybe, she said, but I still wanna know.

Redemption threw an arm around her. “And you wouldn’t be you if you didn’t,” he laughed. “I gotta go pick up the lil bro from his class and walk him home, but let me know what you find out, okay?”

Okay. She hugged him goodbye. Give Moss a kiss for me.

He scoffed. “I’ll try, but that boy thinks he grown now.”

Too grown for kisses??

“That’s what I said.” Redemption threw up his hands as he headed off. “Talk soon, love you!”

Love you! Jam waved goodbye and watched him break into a jog, his body moving with an easy grace, then she went to the library to look up pictures of angels.

The librarian was a tall, dark-skinned man who whizzed around the marble floors in his wheelchair. His name was Ube, and Jam had known him since she was a toddler pawing through picture books. She loved being in the library, the almost sacred silence you could find there, the way it felt like another home. Ube smiled at her when she walked in, and Jam took an index card from his counter, writing her question about angels down on it. She slid it over to Ube, and he grunted as he read it, nodding his head, then he wrote some reference numbers underneath her question and slid the card back to her. They didn’t need to talk, which was perfect.

It took her fifteen minutes to find the old pictures, printed on thin, flaky paper and nestled between heavy book covers. Even though Ube hadn’t said she should, Jam considered pulling on the white gloves nestled in the reading desk drawers to use in looking through the books, they seemed that old. But they weren’t in the protected section, so she figured it was fine to run her bare fingers over the smooth and fragile paper. The room she was in was quiet, with large windows vaulting up the walls and domed skylights pouring in late-afternoon sun. Jam sat for a few minutes with her fingers on the images, staring down, turning a page and staring at the next one. They were strong and confusing pictures. Eventually she closed and stacked the books, then lugged them to the checkout counter.

Ube raised a thick black eyebrow at her. “All of these?” he asked. His voice sounded unreal, deep and velvet, something that should live only in a radio because it didn’t make sense outside in normal air.

Jam nodded.

“You gotta be careful with them, you know? They’re mad old.”

She nodded again, and Ube looked at her for a moment, then smiled, shaking his head.

“You right, you a careful girl. Always seen it.” He scanned the books as he spoke. “You treat the books gentle, like they flowers or something.”

She blushed.

“Don’t be shy about it, now. Books are important.” He stamped them for her. “You need a bag, baby?”

Jam shook her head.

“All right, now. Two weeks, remember?”

She hefted the books onto her hip, nodded, and left. They were a weight straining against her arm until she got home, and she took them straight to her mother’s studio. Jam’s mother had been born when there were monsters, and Jam’s grandmother had come from the islands, a woman entirely too gentle for that time. It had hurt her too much to be alive then, hurt even more to give birth to Jam’s mother, whose existence was the result of a monster’s monstering. This grandmother had died soon after the birth, but not before naming Jam’s mother Bitter. No one had argued with the dying woman.