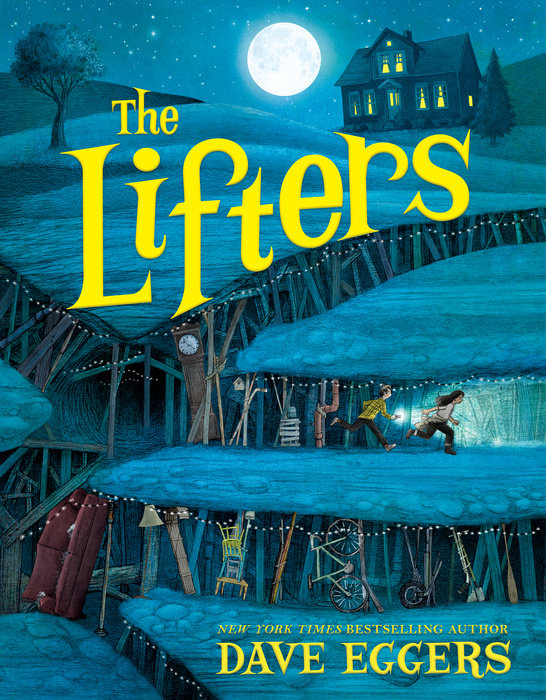

The Lifters

From the Newbery Award-winning author of The Eyes and the Impossible come the story of a mysterious underground world where nothing is as it seems.

What if the ground beneath your feet was not made of solid earth and stone but had been hollowed into hundreds of tunnels and passageways? What if there were mysterious forces in these tunnels? What would it feel like to know the fate of an entire town rested on your shoulders? Twelve-year-old Gran Flowerpetal is about to find out.

When Gran's friend, the difficult-to-impress Catalina Catalan, presses a silver handle into a hillside and opens a doorway underground, Gran knows that she is extraordinary and brave. He will have no choice but to follow her and help save the town (and the known world). With luck on their side, and some discarded hockey sticks for good measure, they might just emerge as heroes.

An Excerpt fromThe Lifters

Gran did not want to move to Carousel.

But his parents had little choice.

His father, a mechanic, had not had steady work in many years, for reasons unknown to Gran.

His mother had had an accident when Gran was young, and was now in a wheelchair. His parents never explained quite what happened, and Gran didn’t feel right asking. After a while, when people asked Gran about his mother’s condition, he just said, “She was born that way.” It was the easiest way out of the conversation.

But he remembered when she walked. He remembered that she had once worked as an artist in museums, making the animals in dioramas look realistic. He had a foggy memory of standing, as a toddler, in an African savannah with her as she touched up the whiskers of a cheetah. That was before the wheelchair.

Then Gran’s sister Maisie was born, and his mother hadn’t returned to work. Gran’s father had built a studio for her, enclosing their deck and filling it with easels and paint and…