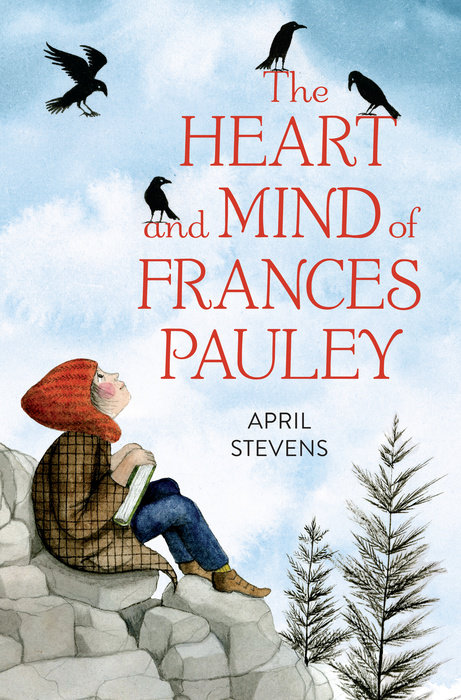

The Heart and Mind of Frances Pauley

Perfect for fans of Jennifer L. Holm's The Fourteenth Goldfish and Holly Goldberg Sloan's Counting by 7s, and called "nothing short of magical" by The New York Times, this heartfelt, deeply moving middle-grade debut features an offbeat girl who learns that she can remain true to herself while also letting others in.

Eleven-year-old Frances is an observer of both nature and people, just like her idol, the anthropologist Margaret Mead. She spends most of her time up on the rocks behind her house in her "rock world," as Alvin, her kindhearted and well-read school bus driver, calls it. It's the one place where Frances can truly be herself, and where she doesn't have to think about her older sister, Christinia, who is growing up and changing in ways that Frances can't understand.

But when the unimaginable happens, Frances slowly discovers that perhaps the world outside her rugged, hidden paradise isn't so bad after all, and that maybe--just maybe--she can find connection and camaraderie with the people who have surrounded her all along.

Original, accessible, and deeply affecting, April Stevens's middle-grade debut about an unforgettable girl and an unlikely friendship will steal your heart.

An Excerpt fromThe Heart and Mind of Frances Pauley

Chapter One

Unlike her sister, Figgrotten went right outside after school and climbed the rocks behind their house and looked for things. Mostly birds, but bugs and different stones too. She had made herself a kind of room up on the rocks. It had sticks around it for walls and a built-in rock-chair that had moss growing on it, and it had a dent that sometimes, after it rained, served as a nice sink.

Figgrotten’s sister, Christinia, on the other hand, would go straight to her bedroom and make her bed and put away all her clothes and dust her furniture, then put on sappy music and stare at herself in the mirror. She had long hair that she kept perfect and pinned.

Figgrotten did not even try to manage her own hair, as it was not that kind of hair. It felt like dry grass, and after a bad experience with a burr once, she kept it shorter and most often wore a hat. It was one of those hats with the earflaps that hung down. She wore it not only to cover her hair but also because when she wore it she felt snappier. Christinia found the hat an embarrassment, and this seemed to be another reason Figgrotten liked to wear it. She’d discovered that the more Christinia hated certain things about her, the more she clung to those things in defiance.

Her best friend in the whole world, Alvin Turkson, was always saying, “People have to accept each other or wars break out.” But Christinia was the opposite of accepting, in fact, she seemed downright intolerant of Figgrotten these days. At night, when her sister would strum her guitar in her bedroom next door and sing in her beautiful voice, Figgrotten’s heart would get tugged at and a loneliness would come over her. She would have liked to go in and sit with Christinia and tell her she loved her singing, but now she knew to keep her distance.

Chapter Two

Figgrotten had been going up to her rocks for years. It was where she felt most herself. Sometimes she was out there until after dark and Christinia would come out on the back lawn and say the word “dinner” in a sour, disgusted voice and Figgrotten would climb down and go back inside. The fact was, she hated being inside. She felt like she couldn’t breathe indoors. Especially at dinnertime, when she was made to take off her hat and wash her hands and eat in the stuffy kitchen.

Often, at dinner, she’d ask questions that seemed to confuse her family. Things like “I read that Margaret Mead used to just hang up the phone when she was done talking to people. She didn’t even say goodbye. Just clunk, put the receiver down. Do you think that was because the people she studied didn’t have telephones?” Figgrotten really liked Margaret Mead, an anthropologist who had studied tribes of people living in the middle of nowhere without telephones or toilets. The thing that had drawn Figgrotten to her to begin with was a photograph she’d found of Margaret Mead in the World Book Encyclopedia. She looked a bit strident, wore a cape and a hat, and carried a walking stick. At first Figgrotten even thought her face looked kind of manly. She stared at the picture for quite a while. Then she started reading about Margaret Mead’s life and found it super interesting.

She’d never even heard of anthropology before this, but once she did, she thought it might be something she might like to do when she grew up. Mostly because it involved a lot of outdoor work. One thing Figgrotten knew for sure was that if she had to work inside somewhere, she’d probably suffocate. But the other thing that she liked about anthropology was that it involved observing people, and Figgrotten was a natural observer. She observed birds and trees and clouds and, once she stopped to think about it, she did lots of observing of people too. Her sister, of course, being one of those people. Not because she found Christinia all that interesting, but more because she was trying to figure out exactly what made her tick.

Figgrotten kept her bedroom windows open at night, and she’d brought a lot of branches up there so that it felt kind of woodsy. Initially this exasperated her mother, but now her mom didn’t go into her room as much. She told Figgrotten that she just couldn’t take the mess. At first Figgrotten wasn’t sure what to make of her victory, but soon she came around to it. Not having her mom come in there all the time and yell at her about all the leaves and sticks actually made life in the house calmer.

Due to the open windows, Figgrotten’s room would get super cold in the winter, which was how she liked it. She slept in her wool hat and socks, and sometimes, when it was really blowing in there, she wore her wool coat to bed. She’d bundle up and lie stiff as a board and breathe in the cold clear air. She loved it! Loved the way the air hit the back of her throat, startling her a little each time.

Back when Christinia was still talking to Figgrotten, Christinia would go into Figgrotten’s room and just about go berserk. She’d beat at the branches and get all crazy that the place was so untidy.

“What is the matter with you?” she once shrieked. “Why can’t you be normal? And why do you have that stupid name pinned to your door? That’s just so weird!”

Christinia was referring to the name Figgrotten, which Figgrotten had given to herself a few years ago, writing it out in her then-crooked handwriting and tacking it on her door. Her real name was Frances Pauley, which she felt didn’t suit her, so she put all sorts of words together, backward and forward. Once “fig” and “rotten” rolled off her tongue together that first time, it stuck. And from then on she thought of herself not as Frances but as Figgrotten, adding the extra g because that’s the growly way it sounded to her. Giving herself this name felt strangely freeing. It allowed her to be able to just be herself more. Not Frances. But Figgrotten.